Newspeak: Why silence defeats “thought crimes” in Orwell’s 1984

- Linguistic determinism is the notion that language is necessary for thoughts to exist.

- But the brain’s primary tools for thinking are actions, feelings, and images, not words.

- The language and narration that describes our thoughts come afterward.

Speech is often taken to be linguistic and communicative with the unique power to represent things. Thoughts are characterized by language because thoughts represent things. Silence, by contrast, is taken to be uncommunicative and, therefore, incapable of representing things. But thankfully, this is not true.

Linguistic determinism and Orwellian Newspeak

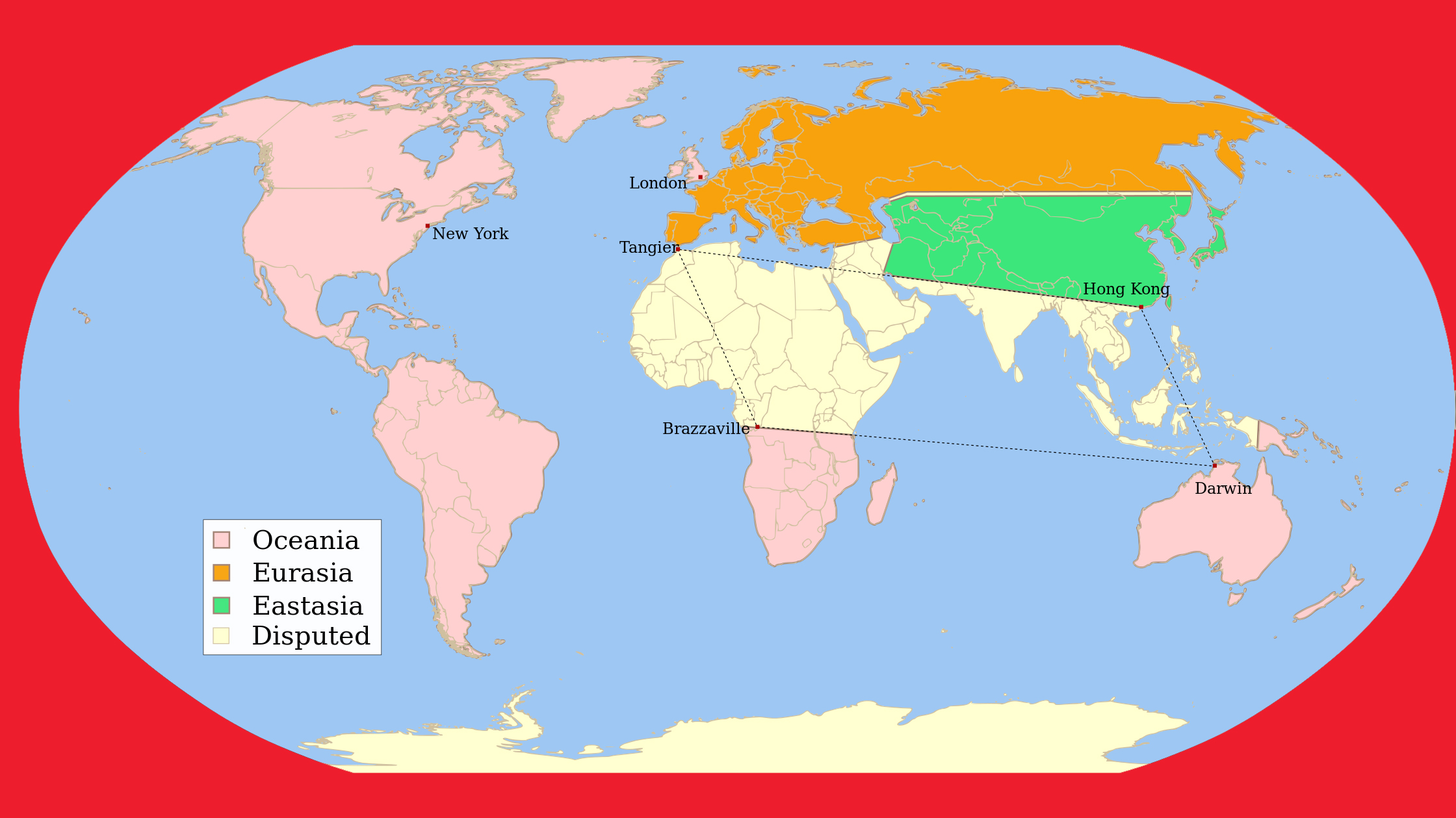

Linguistic determinism is the view that, in order to have thoughts, one must have the ability to use language. Thus, in order to communicate and represent things to oneself and others, these abilities are constrained by one’s linguistic abilities. One of the best examples of linguistic determinism can be found in George Orwell’s 1984.

In the dystopian novel 1984, “Newspeak” is the governmentally imposed restriction on certain forms of speech and, as a result, thought. Ingsoc, the totalitarian regime, imposes restrictions on its subjects’ vocabulary. The intention of these restrictions is to ensure that new generations are rendered completely incapable of certain forms of thought — namely, thought that goes against the Ingsoc narrative. If Ingsoc’s subjects cannot verbalize rebellion, they cannot even think about rebellion. As Orwell states in 1984’s appendix, “Newspeak was designed not to extend but to diminish the range of thought, and this purpose was indirectly assisted by cutting the choice of words down to a minimum.”

Thoughts do not require language

1984, despite conveying the destructive power of limiting language, likewise conveys the impossibility of limiting human thought through limiting language. Despite the predominance of Newspeak in 1984, its characters are still capable of thinking about rebelling and how horrible Ingsoc is without being able to put words to these thoughts.

Indeed, such thoughts were demonstrated through actions. “The sexual act, successfully performed, was rebellion. Desire was a thoughtcrime.” For what is sex but to communicate one’s thoughts of love or desire, physically instead of linguistically? Thoughts simply cannot be limited to language. Language is merely one way, among many, in which thoughts are conveyed.

Consider memories. When reminiscing, an image or feeling may come into your mind’s eye — perhaps the image of a fish you caught with your parents as a child, accompanied by the joy that you felt upon catching it. These images and feelings are thoughts, but they do not entail language. Sometimes, thoughts are accompanied by language, but often thoughts are just images and feelings. Language, in fact, most often comes after such images and feelings, not before as is implied in linguistic determinism.

Spinoza and affective neuroscience

Baruch Spinoza’s views on thought were similar. Spinoza believed that imagination was another example of thoughts that do not always entail language. Imagination, like memory, is characterized by images and feelings. When I was a child, I would daydream about playing dodgeball at recess. I would literally see myself and my friends playing, and I would feel excited. Perhaps sometimes I would narrate these images and feelings — “I can’t wait to get outside!” —but not always. Often, I would simply relish in these mental fantasies, without a word being expressed.

Affective neuroscience likewise affirms this view. Language is not the brain’s primary tool for thinking: rather, actions, feelings, and images are its primary tools. All thoughts which use language are actually based on thoughts which entail no language at all!

Consider, for instance, when you reached for your doorknob to leave your home in the morning to go to work. Did an internal narration precede this action? “I’m going to work now, and I am going to grab the doorknob, and then I’m going to lock the door behind me!” No, of course not. According to Heidi M. Ravven, a researcher at Hamilton College, “Thought is embodied; it is first and foremost about the body.” Language and narration come after, not before, actions, feelings, and images.

This does not mean, however, that thoughts never entail language. But imagine how impossible thinking with language would be without our inner emotional life, internal imagery, and behaviors? Without such a basis, words would be neuropsychologically impossible. Just as we cannot genuinely express the love we have for a person through language without the feelings to back up our words, we cannot make children laugh about Humpty Dumpty unless we have the initial picture of a dim-witted egg in our mind’s eye.

The ethical implications of silence

An understanding of the nature of thought might sound abstract, but it actually has practical implications. Historically, linguistic determinism has been used to classify who or what is and who or what is not to be morally regarded. Language has been taken to be what signifies consciousness, which is often believed to be the criterion for moral regard.

For a long time, animals were given little or no moral regard due to their lack of language abilities. Descartes inferred that animals have no consciousness because they lack language — and, as a corollary, that humans are the only beings deserving of moral regard. Descartes went so far as to call animals “sophisticated automata,” performing vivisections on animals on the basis of this fallacious view. Today, children suffering from mutism are more likely to be abused at school.

It is ethically imperative that we discard linguistic determinism. This is one of the more subtle morals about Newspeak from 1984.