“The self” doesn’t exist. Instead, you constantly shape multiple selves

- The self is a complex and dynamic construct influenced by personal experiences, cultural background, and beliefs about oneself and others.

- Our interactions with others can affect our sense of self, and there is a tension between the desire for coherence and the desire for freedom in our self-perception.

- The concept of self is not static, but rather constantly evolving through social interactions and the ongoing construction of our identity.

Right now, as I search for the words to express my thoughts to you, I alternate between feelings of frustration and ease. I am certain my self—not you, not anyone else—is having this experience. And you are having your own experience as you read these words. I feel completely whole, able to move through the world and interact with others, or not, as I see fit. I assume you feel the same way: you know that you are you, a bundle of experiences, wants and needs, actions taken and avoided, all made coherent because they flow from a single source: you.

As we go about our days almost nothing feels as immediate, as wholly our own, as our selves. You are always in there somewhere, thinking and feeling, directing action, like a little “you” managing the controls. But when we take a closer look at the idea of the self as a person inside us, cracks start to emerge.

I have studied social psychology for the past twenty-five years, and I can tell you that our felt experience of the world doesn’t always align with what the research shows us. Imagine you won the lottery and all your financial problems vanished. You can suddenly pay for everything you need and buy just about anything you want. Wouldn’t that be fantastic?! Research suggests it probably wouldn’t be as good as you imagine. We’re not actually very good at predicting the way we will feel in new situations. We tend to overestimate in both directions; we think terrible things will feel worse than they turn out to and expect good things to feel better than they do. We have theories, ideas about ourselves in the world—some accurate, others less so. What we don’t have is direct access to the way we actually work.

Think of it this way: when we engage with the world, we do so in a way that makes sense to us without needing to understand the incredibly complex processes taking place inside us or the equally complex interactions between us and the external world. It’s like the little icons on a computer, our user interface if you will. When you put an item in the “trash,” the little icon isn’t moving into a trash can. Highlighting something and dragging it to the trash is just a representation of a much more complex set of processes. We engage with the social world in much the same way.

So, when you think, “I love my partner,” it’s an interpretation of feelings—physical signals from complex biological processes—based on to the way relationships work in your culture and your personal history. You’ve learned what love means and looks like in your culture. Your personal experiences have taught you, among other things, to be guarded or free with your emotions, which affects your willingness to label an experience of someone as love. You can name some of these cultural and personal influences, but others you don’t understand or even have access to. Who is to say what past experiences, large or small, were necessary to love our partners? Who knows if in another time or place we would have loved the same person? None of this makes the love we feel right now less real or important; it simply highlights how deeply enmeshed we are in our social world, and how much it affects who we are.

It’s obviously not just who we love. What we think of as right or wrong, for example, is also deeply affected by the social world we inhabit. Should children be allowed to play away from their home without supervision? At what age is marriage appropriate? Under what circumstances, if any, is it okay to kill another human being? Answers to these questions have differed across time and continue to differ across cultures and communities.

If you read any of the wildly popular self-help books out there, you might get the impression that we should not want to be shaped by our social environments. Many of these books focus on helping you be unapologetically, unreservedly, your true self. This book doesn’t argue against this aim so much as argue that it’s not possible. People want and need social engagement, which means we can’t live completely free of external influences and constraints.

Much of what we want to think about our selves doesn’t match reality. Many of us think we are smarter, better looking, and nicer than we really are. When we do good things, like donate money to a charity, we think it’s because we’re good people. When we do bad things, ignore people in need, we think it’s because of circumstances beyond our control. We also have a sense of knowing more than we do about our own psychology. For example, our beliefs about the world often shift, sometimes in ways we don’t understand, in response to the beliefs of others. In other words, we are constantly getting things wrong about the way we work. But this is not a book about all the ways we mess up or are messed up. Rather I want to focus on our sense of what we are, what it means to have and be a self.

Our self is a construction of relationships and interactions, constrained and yet in search of the feeling of freedom. This tension, the need to exist in a coherent way and the desire to do and be whatever we want at any time, defines much of what it means to be human. Where do our experiences of self come from, why do we need the feeling of freedom, why is there a tension between self and freedom, and why does any of this matter?

Our experience of the self must come from somewhere. Our interpretation of our decisions—the story we tell ourselves about who we are—must come from somewhere, and we’ve looked in a lot of places. Early on, Sigmund Freud theorized that the self was closely tied to sexual development. In the early 1900s, American sociologist Charles Cooley asserted that a person’s self, at least in part, is constructed by how they think other people see them—he coined the term “the looking glass self.” In the 1930s, sociologist George Mead claimed that the self is developed through social interaction. If you couldn’t see yourself through the eyes of others, Mead would say you have no self. Of course, the idea of the self isn’t just scientific. Cultural movements have claimed that the self is innate—you’re born a certain way and you will not change. Or that your self is handed down from above—God created you. Some Calvinists, for example, believed that people were born predestined for eternal life or damnation.

When you see me what do you see? A man? A Black guy? A professor? Someone in a hoodie? A threat to you, or a new friend?

The truth is, if we meet and interact, you don’t just see me. You see what your relationships have taught you about people like me. If you’re a native of the United States, we see our shared racial history through the lens of current social concerns like the Black Lives Matter movement. We see each other’s gender through recent shifts in gender expectations—maybe we even state our pronouns. You might see me as a professor and engage me around your beliefs about professors’ political views. Do you feel comfortable with me, or do you worry I am judging you? Do you assume we’re peers or that I am higher or lower status than you? Do you assume we agree on important issues? Do you enter the interaction expecting us to be friends? What you believe about me affects the way you interact with me; your beliefs and actions, in turn, affect the nature of my self. Whether I accept or reject your view of me, it will change me. We bring multifaceted selves to our interactions, and in these interactions co-create each other again and again.

Selves don’t emanate from some ineffable light within people. Instead, selves are created in relationships. In every interaction, others—your partner or friend, a neighbor or a stranger, a delivery person or a police officer—offer up their view of your self. They may not directly say “this is how I see you,” but they show you in the way they treat you, the way they speak to you, and even in subtle body language. In every interaction people say something about who they think you are. Do they smile, do they seem fearful, are they rude or respectful? Every interaction offers you a chance to “see” your self. In fact, the only way to see your self is through social interactions.

What people reflect back to you isn’t some “true” representation of what or who you are, nor of what they are. It’s a construction filtered through the self of the person you’re interacting with. As is their self, in that moment, co-created by you. In the hall of mirrors, we see our selves reflected, or perhaps refracted, in the multitude of people who surround us.

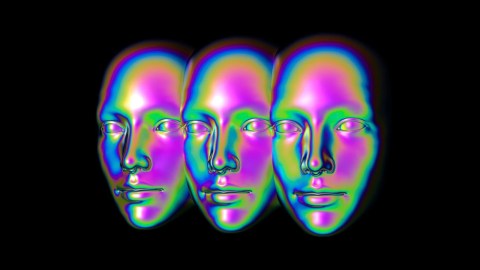

This leads to an important question: When you wonder whether what you say or do is best for your self, you must ask: Which self? This might sound like something out of a psychological thriller, wherein one person is both sweet and murderous. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—one body, but two (or more) distinct selves. Turns out a version of this plot device, though a much less sensational version, is true for all of us.

We all have multiple selves (parent, child, employee, athlete, lover, etc.). And each of these selves is defined in a web of relationships and has particular attributes. What determines which one we are in any given situation? The biggest determinant of who you are is probably where you are. And by “where you are” I mean all the features of your situation: physical location (restaurant versus home), company you’re with (friends versus family), nation you’re in, and even the time of day. You are a different self at drinks with college friends than at drinks with family after dinner. Think of the last time you were out with close friends. Think about the way you spoke, the language you used, how loudly you spoke. Think about what a stranger looking at you might have thought. Now think about the last time you were in a professional setting, maybe an office meeting. Almost certainly you behaved differently. At least I hope you did. You might think you were the same self, but is that really true? Did you feel the same way? Probably not. Both of these “selves” are you, but consider the possibility that they are different yous.

Here is the kicker, which probably won’t come as a surprise: the contents of our identities are sometimes in conflict. In the United States what comes to mind when you imagine a professor does not align with mainstream social depictions of Black people. When I first walk into a classroom people don’t always assume I am the professor. I also have to reconcile my identity as a Black man with my identity as a professor, because I have to manage the relationships that constitute these identities. I am keenly aware that my social status as a professor at a prestigious university is higher than my status as a Black man. Should I display my status as a professor to counteract the social costs of being a Black man? Claude Steele, an eminent social psychologist, tells the story of a young Black graduate student whistling Vivaldi while walking at night in White neighborhoods to assure White people that he is not what they consider a “regular” Black man. But if I “whistle Vivaldi,” am I in that moment trying to deny being Black, and in doing so, am I betraying what it means to be a member of the Black community?

To see how people manage conflicting identities, social psychologist Margaret Shih designed a study that examined AsianAmerican women’s relationship to math. As Asian Americans they are stereotyped as more proficient at math, but as women they are stereotyped as less proficient at math. To study this, Shih and her colleagues asked a group of Asian-American women to self-identify differently: sometimes as Asian American, other times as women. And then they gave them a math test.

When asked to provide their ethnicity before the test, the participants in the study performed better than those asked to identify their gender. All that had changed was a shift of the mirrors around them, a shift in their reflections. And yet, real outcomes shifted.

This underperformance is most often attributed to the cost of knowing that people expect you to underperform. But that is a change in self: the anxiety that affects performance is tied to a change in relationships that define the self. When people thought about themselves as Asian American or as women, their relationships with others shifted and their test performance changed—a tangible result. And that is a literal change in their selves.

The self is what others reflect back to us. Think about your life. As you navigate the terrain of your social world, how often do the mirrors that constitute your self shift or tilt? One moment you’re a parent, then an employee, next a friend. Each of these selves has a bundle of expectations and responsibilities baked in. What tests are you acing or failing because your self has shifted without you even knowing it?

But just as the idea of an unchanging self is an illusion, so too is the unfettered freedom that modern society seeks for the self. Being a completely free self isn’t possible because without the constraint imposed by relationships you wouldn’t have a self at all. You can’t be yourself by yourself. Our understanding of the relationship between self and freedom organizes much of our life and society. There is tension between our desire for autonomy and free will, and the constraints necessary to produce a coherent self in the first place. We sometimes chafe against limits imposed by others, be they friends, lovers, or governments, while seeking out relationships to make life livable and coherent. Who or what would we be without ties to the people and communities that define us? Selfless, perhaps free, but certainly lost.

The idea of being left alone, of being free from external constraint, assumes a clear understanding of the difference between internal and external forces—we feel free when we believe that our thoughts, feelings, and actions are driven by internal forces. The question is what counts as internal. If someone asks to borrow a book from you and you give it to them, was the action free? What if the person who asked to borrow the book only did so to make you feel important? If it worked, but you didn’t know that was their intent, was your action driven by internal or external forces? In the first case, you might think you freely lent the book; in the second case you might feel like the person manipulated you. In both cases, you responded to the other person’s actions; the difference is your knowledge of their intent. You might say that you don’t have the information necessary to act freely if the person misrepresents their intent. But what if the person doesn’t fully understand what’s driving their behavior? When you drill down, the line between internal and external forces is less clear than it might seem.

Let’s explore this distinction between internal and external. Right now, think about the little finger on your right hand. Wiggle it a bit.

We just shared a moment, a little dance across time and space. I had a weird idea, wrote it down, and then you, wherever and whenever you’re reading this, acted on it.

There are almost too many moments of magic to count in that little dance. For starters, the incredible complexity of the publishing industry and the many thousands of people necessary to physically make the computer I’m writing this on and the book or device you’re reading it on. But here, what matters most to me is that my thoughts affected your behavior. What does that say about your self? Was your self, the one reading this book, truly separate from mine? Were you free in spite of my presence? Was I—alone, writing at my desk months or years before you read the words I wrote—truly free while imagining you? Or was I constrained by my imagination of you. I don’t know you, but I imagine you as a smart, curious, critical reader, and this version of you—in our interaction right now—demands something of me, and thus shapes me at this moment. The idea of you has affected my behavior and what I chose to share in this book, long before you read it. I’ve read books with you in mind. I’ve even read this book out loud to see how you might hear it. You have, in other words, made me a writer!

This is to say that the way we define our selves, the separation between you and me, is entwined with the way we think about freedom. I have affected your actions and thoughts, and you’ve also affected mine, even though we have probably never met.

When you wiggled your little finger, or just thought about doing so, was it my thought or yours that created the action? Did I do something to you? Or did your action bring my thought to life?

Obviously, both are true. If you wiggled your finger, you chose to do so; I couldn’t force you to do it. At the same time, you almost certainly wouldn’t have done so if I didn’t suggest it. And even if you didn’t wiggle your finger, you thought about it. You really couldn’t have read the sentence and not considered it. If you didn’t do it, you chose not to. So even though I didn’t compel your action, I did compel a decision. What does that say about my relationship to your self? If you think of your self as, in part, the decisions you make, I just shaped your self. If you think of freedom as freedom from others’ influence, I just hampered your freedom. This tiny little interaction between us is a microcosm of your day-to-day life.

Think about your typical day. If you’re like me, your day revolves around other people. If you live with other people, soon after you wake up you’re navigating relationships: sharing the bathroom; eating with partners, children, or roommates; answering emails and messages from friends or colleagues. You also interact with people you will never meet: maybe you’re reading the news about people in some far-off place, the goings-on of celebrities, the announcements of elected officials. All these interactions can take place before we even leave the house for the day.

Now consider the countless encounters, both planned and completely incidental, that occur throughout your day. All these interactions demand something of you; more importantly, they affect you. Of course, most of the people you walk past barely register, but that doesn’t mean these fleeting interactions have no consequence: even one person seeing you as attractive or unkempt, a threat or a friend, can transform everything you think and do that day. Imagine that your partner or roommate questions the way you’re dressed just before you leave the house. Maybe their comment undermines your confidence. You start to worry about the way others will see you. At work you feel less confident giving that big presentation, and it doesn’t go as well as it could have. You feel a little less extroverted than normal after work. Maybe you’re not as talkative around strangers you bump into. You come home and you’re in a bad mood and maybe have a fight with your roommate or partner. This can sound like just a bad day, but these effects reverberate. Maybe you like your job a little less after that lackluster presentation and feel less tied to your professional identity. Or maybe your bad day intersects with your partner’s insecurity and a resulting fight forever changes the way you see and interact with each other. Small causes can create big effects.

The behaviors of others affect the way you, in turn, behave in the world. Even when you were reading a book “all by yourself,” suddenly a choice was forced upon you by someone you couldn’t even see. What other choices are you being forced to make, and by whom?

Society is an intricate social game. We depend on others following rules we understand, and responding, often without thought, to what we are doing. Even if we can’t describe the rules, they shape the way we behave. If you ride public transportation, you probably know you don’t sit next to someone if an open seat is available farther away. At least in the cities I know, you also don’t talk to strangers and generally try to mind your own business. These unspoken rules help minimize uncomfortable situations and disruptions of our daily commutes. The order they provide makes the ride a little easier to tolerate, saves us energy for the day ahead, or allows us to ease into our evenings.

To make it through our days, we need the world to have order. We also need to believe that what we do affects the world, and that the outcomes of our behaviors are, at least in theory, predictable. Imagine you are trying to lose weight. You’re doing everything you’re supposed to—eating less and exercising more—but you aren’t losing weight. It probably wouldn’t take too long before you give up. Imagine the same thing for any other area of life, for example your finances—you work and work, but rising prices mean you can’t gain any ground. It would be really tough to believe that nothing I do matters, and only a little easier to accept that I can’t predict how what I do will affect me or other people. The order we perceive or construct is necessary for the feeling that our choices matter, that we can in fact choose outcomes.

My goal isn’t to push an argument about your ability to decide, but to have you ponder the possibility that the boundary between your and others’ selves might not be as clear-cut as it seems. What does it mean, to you, if your self is not what you thought? What does it mean, to you, that the way you engage with others remakes them and affects their relationships? Maybe it would reshape the way we define “our” communities. They might become more expansive, more diverse, more vibrant. Maybe we would take our interactions more seriously. Maybe we would take more responsibility for the state of our relationships and communities.

With a better understanding of self and freedom in hand, we can turn to a different question. What function does self serve? Why do we even need self? Today we just assume the existence of an individual, self-contained, autonomous self, but why? Do we need this idea to function as a community? We need self, at least in part, because unfiltered reality overwhelms us. Self provides order that helps us function. Self is a point of view. Self helps us manage a world that exceeds what we can imagine. Self is a social structure that allows you access to the ultimately unfathomable, blooming, buzzing chaos of reality. A well-functioning self provides a sense of predictability, stability, and certainty.

We immediately understand people and social situations based on often inarticulable cultural and personal information. For example, when someone enters your personal space you feel uncomfortable, but what constitutes too close depends on things like your relationship with the person and where you’re from. No one told you how far away strangers or friends or family should stand from you, but nevertheless you know. You probably don’t experience it as “that person is standing too close for a stranger in Norway” or Spain or wherever. It’s just the feeling that someone is inappropriately close to you. Where did that feeling come from? As I’m sure you know, personal space differs based on your culture. The existence of personal space is universal, but our community determines the way this universal need is experienced. It’s the product of unspoken rules you picked up from those around you. The influence of our community is profound, whether we can articulate it or not.

Research finds that humans recognize nonverbal “emotional expressions” regardless of where someone is from. If you’re from Germany, you still know what fear looks like in someone from Ecuador. But it turns out that there are community accents in emotional expressions. In one clever study, researchers from Harvard University displayed pictures of either Japanese or Japanese-American people showing either neutral or emotional (fear, disgust, sadness, surprise) facial expressions. Importantly, the photos were designed to eliminate cultural differences in appearance, so for example, the clothing on each subject didn’t give hints as to their nationality. Nevertheless, people were significantly better than chance at telling the difference between a Japanese person and a Japanese-American person, and they were significantly better at telling the difference when the person was expressing emotion. In other words, people can identify incredibly subtle, community-created differences in the way people express emotion. We can recognize members of our communities because we know what the influence of the community looks like. Things as personal as your expression of fear and sadness bear the mark of those who define you.

This is all to say that your self is constructed and reconstructed in a swirl of ever-evolving relationships. The ideas that live in these relationships and interactions provide the social identities—for example, gender, ethnicity, professional identity—that we use to make sense of ourselves and others. This self situates you in the world, it provides a perspective, a vantage point, from which you experience the world. The construction of self might be complex, but the experience is pretty straightforward. But there are no free lunches. The simplification that a self provides comes at a cost.