Satanic cults aren’t as bad as they sound

- The general public tends to view Satanic cults as sadistic and dangerous.

- In truth, modern-day Satanists are non-violent activists who treat Satan not as the embodiment of evil but a symbol of resistance against arbitrary authority.

- Using their status as official religions, cults like the Temple of Satan run campaigns to protect LGBTQ and abortion rights.

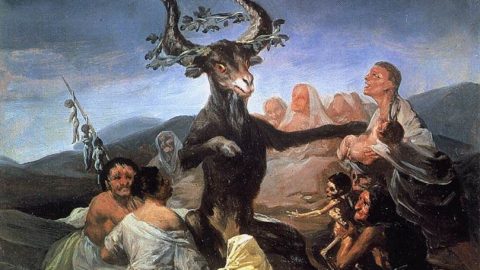

What do imagine when you try to picture a Satanic cult? You might think of movies like Rosemary’s Baby, which follows a woman whose creepy neighbors trick her into giving birth to the antichrist, or The Exorcist, about a girl possessed by a demon. If you grew up during the 1980s, your impression of Satanic cults was probably influenced by the sensationalized McMartin preschool trials, in which teachers were accused of conducting hellish rituals with their own students.

Despite their influence in pop culture, none of these accurately portray Satanic cults or the people involved in them. The Exorcist says less about Satanism than it does about the Roman Catholic Church, where exorcist and Devil’s advocate were (and remain) actual professions. And McMartin’s teachers, to the surprise of paranoid parents, were acquitted for a lack of evidence. (In retrospect, it turns out that investigators and psychologists stimulated the children’s imagination to the point they produced fabricated testimonies.)

In their article, “Satanism in Contemporary America: Establishment or Underground?” Diane E. Taub and Lawrence D. Nelson reveal just how different the general public’s perspective on Satanic cults is from that of the average scholar. While “the antisocial and criminal aspects of Satanism have been the focus of most lay writing and media,” they write, “sociological discourse has generally represented Satanism as a harmless, law-abiding alternative religion.”

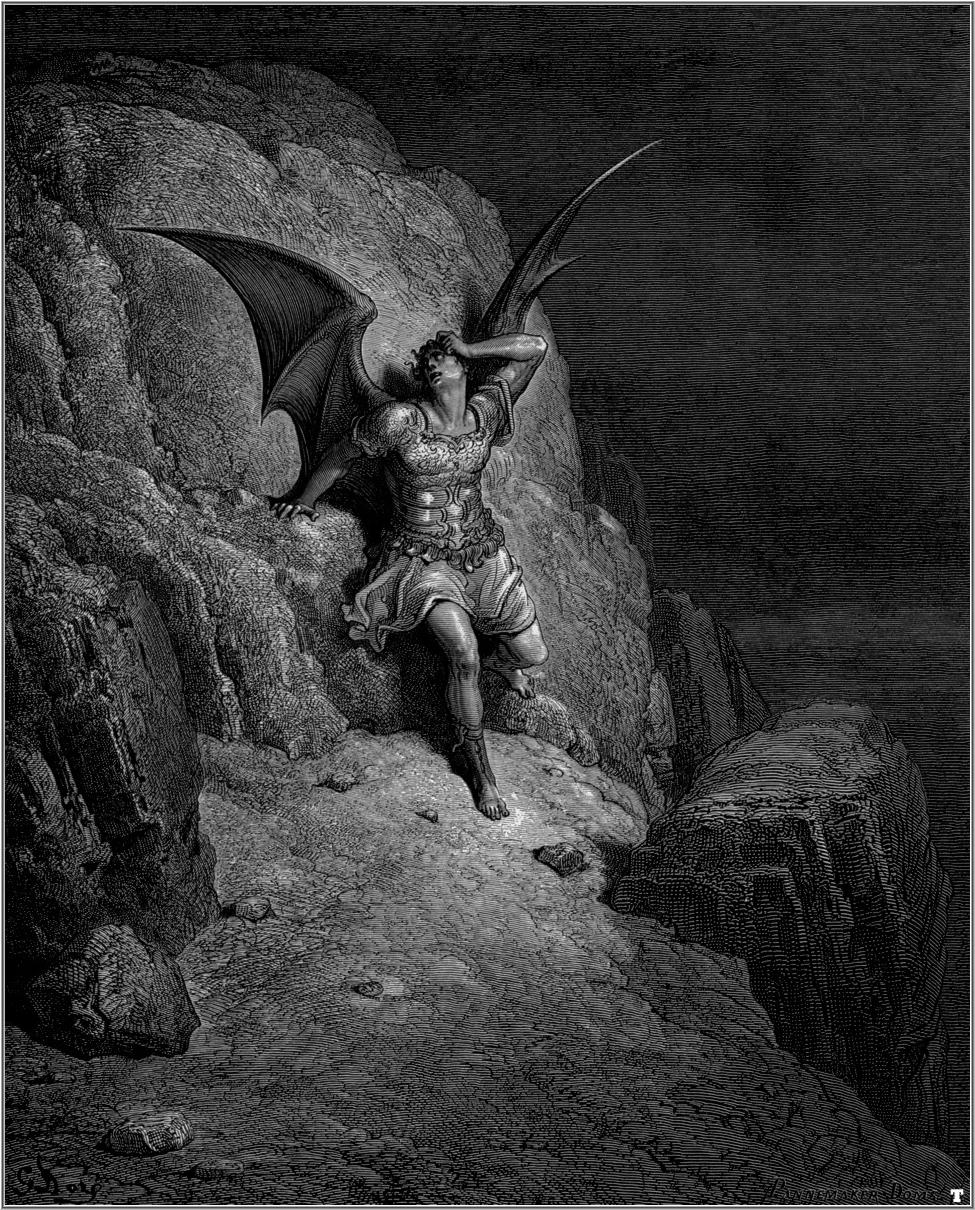

Journalist La Carmina arrived at the same conclusion while researching her latest project, The Little Book of Satanism: A Guide to Satanic History, Culture, and Wisdom. The booklet, published by Simon & Schuster with a foreword from Lucien Greaves, a cofounder of the Satanic Temple, was written in part to help clear up Satanism’s besmirched reputation. “Modern Satanists,” La Carmina insists, “are nonviolent and for the most part nontheistic, meaning they don’t believe in the existence of the Devil.” They don’t sacrifice animals or infants, and they don’t pray to an irredeemable Prince of Evil. “Rather, Satan — the fallen angel who defied God — is a metaphor for the revolt against superstition and arbitrary authority.”

The meaning of Satan

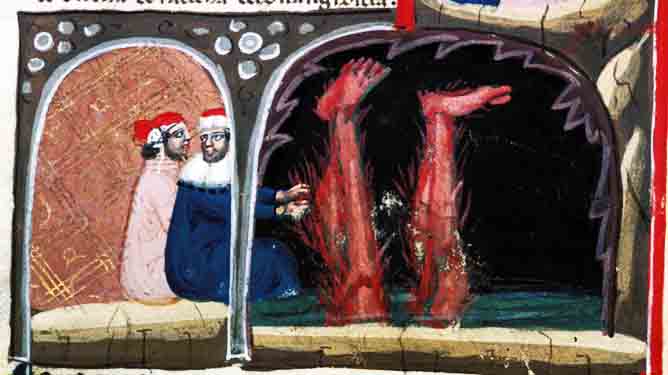

The Satan at the center of modern-day Satanic cults is not the Satan we find in the Old Testament, who uses pain, deceit, and misfortune to test the piety of people like Job. Nor is he the Satan of the New Testament, who appears to tempt Christ, cementing himself as God’s semi-autonomous adversary.

Rather, the version of Satan worshipped by organizations like the Satanic Temple and the Church of Satan is the Satan introduced in John Milton’s 1667 epic poem Paradise Lost, one of the first pieces of literature that depicts the Devil in a positive light. Milton’s Satan, known as Lucifer before his fall, is a charismatic anti-hero who rebels against heaven and pays dearly for it. The poem suggests Lucifer is driven not just by his lust for power, but also a desire to acknowledge his own individuality, a flawed albeit sympathetic cause.

When the subsequent Age of Enlightenment called the Christian worldview into question, fascination with God’s traditional adversary continued to grow. In this new context, Satan came to symbolize not just individualism, but also rebellion against an arbitrary, incompetent, or unjust authority. Both of these themes are integral to modern-day Satanism.

Where conventional religion preaches selflessness and conformity, Satanism champions tolerance and freedom of expression. One of the Church of Satan’s tenants is “indulgence instead of abstinence.” This might sound like an indiscriminatory embrace of carnal desires — well, because it is — but it also implies that a person should not be shamed of their sexuality. Similarly, the Satanic Temple’s tenant that “one’s body is inviolable, subject to one’s own will,” is really just another way of saying, “my body, my choice.”

These tenants encourage an alternative reading of religious texts such as the Book of Genesis. In this book, a snake convinces Eve to eat the Forbidden Fruit despite God’s warning, causing her and Adam to be expelled from the Garden of Eden. Though this is not a mainstream Christian interpretation, some have interpreted the story as Eve being weak (while Adam supposedly would have resisted), and some men have used this as an excuse to treat women as inferior.

A “Satanic” take on this interpretation of Genesis, by contrast, paints Eve not as flawed but as courageous. Instead of committing a sin, she merely stood up for herself by refusing to accept her subservience to Adam and attempting to gain knowledge and power she was arbitrarily denied by her creator.

Satanic cults as vehicles for social change

Central to Christianity is the importance of turning the other cheek. Just as Christ suffered torture and injustice on the cross, so too should Christians endure the many hardships they encounter over the course of their lives. It’s a beautiful and rather convincing ideology. Unfortunately, it sometimes is used — incorrectly — as an argument for why the powerless should accept their subjugation to the powerful.

Here, too, Satanic cults disagree with conventional religion. Instead of turning the other cheek, the Church of Satan calls for its followers to enact “vengeance.” The alarming rhetoric notwithstanding, this is not a call to violence: Researchers from the 1970s and 1980s repeatedly described the organization as peaceful and law-abiding. On the contrary, it is a call to action, to address wrongdoing rather than suffer it in silence.

The Satanic Temple in particular has cemented itself as a vehicle for social change. In recent years, the organization has been adamant in its support for women’s reproductive rights. As a religious institution recognized by the IRS, the Satanic Temple can protect the civil liberties of its followers in ways that a secular activist group could not; in 2015, the Temple sued the State of Missouri, arguing that its strict abortion laws violated the religious convictions of its members.

Since then, similar cases were brought before the courts of Texas, Idaho, and Indiana, just to name a few. The Satanic Temple is also a staunch ally of the LGBTQ community. When a Christian baker in Colorado declined to make a wedding cake for gay customers, members of the Satanic Temple called in asking for cakes praising the Devil. While sexual orientation is not explicitly protected by the Civil Rights Act, it’s against the law for businesses to refuse customers based on their religion. As such, the bakery had no choice but to process the orders.

One wonders how effective these campaigns really are. On the one hand, establishing a clear connection between Satanism and abortion probably will not win over a lot of voters. On the other, there’s something strangely admirable about the Satanic Temple using its status as an official religion to protect citizens and civil liberties from the encroachment of other religions.

As Greaves puts it in his foreword to The Little Book of Satanism:

“The ‘blasphemous’ iconography of Satanism is, for most Satanists, a declaration of personal liberation from traditional theistic institutions and the sometimes arbitrary restrictions they impose on their followers, rather than a calculated insult directed at faithful believers with the intention to offend.”