Go ahead and laugh at a funeral. Nietzsche says it’s okay

- Laughter is one of the most ubiquitous and pleasurable things humans do. The why of laughter is as broad and complicated as the human condition itself.

- For Henri Bergson, we cannot laugh when we experience powerful emotions. It’s why funerals are rarely funny. Ethically, it’s hard to find theories which would justify laughing at someone’s funeral.

- For Nietzsche, laughter is the way to ridicule and reduce the absurdity of death. To laugh at death is to free us of its grip.

If you really want to ruin someone’s day, ask them to explain (as you remain unsmiling) why their joke was funny. Watch them repeat the set up and over-emphasize the punchline. Enjoy how they squirm their way through the ins and outs of “why you should laugh at this bit.” Because, after all, there’s nothing less funny than dissecting a joke.

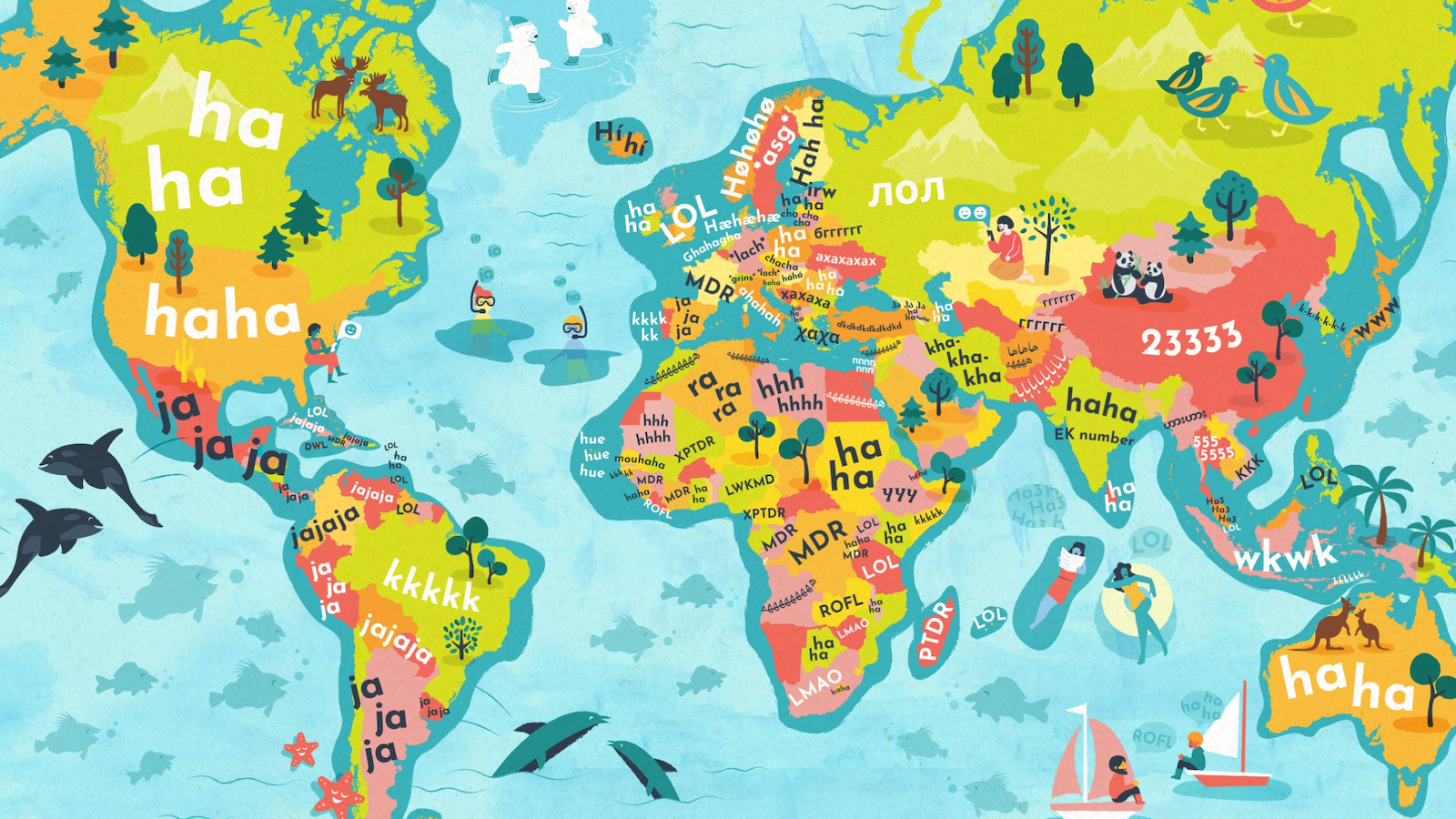

Laughter is one of the most ubiquitous and pleasurable things humans do. It makes a bad day a bit less bad. For many of us, it’s the background feature to our happiest memories. While there is evidence that other animals laugh, no other species does so with quite the same regularity or with such complexity as humans.

The range of what we laugh at has wide and wispy boundaries. We laugh when we’re tickled, but we also laugh at clever word play. Laughter might be a coping mechanism, and it can just as equally be a bonding exercise. And, of course, we laugh at a lot of things — a friend sneezing up milk, cat memes, or a curious-looking root vegetable.

The interesting and philosophical question is this: Are there things that are wrong to laugh at? For instance, is it always immoral to laugh at a funeral?

Too serious to laugh

You have to be in a certain mood to have a laugh. When we’re terrified, sad, or furious about something, it’s hard to find things funny. As the French philosopher Henri Bergson put it, there is an “absence of feeling which usually accompanies laughter. It seems as though the comic could not produce its effect unless it fell, so to say, on the surface of a soul that is thoroughly calm and unruffled.”

Bergson believed that laughter must “appeal to the intelligence” with a “momentary anesthesia of the heart.” This does not mean humor is a cold and lifeless affair, but rather Bergson’s point is that if you are too invested or tied into the drama of a situation, there is no laughter to be had in it. For example, as we dance in the sweaty step of a crowd, with music in our ears, everything seems natural and normal — there is little funny about it. But stand on a balcony, looking at a mob of people dancing to a silent disco, and suddenly there’s something ridiculous about it. You are no longer part of the drama or situation. In Bergson’s terms, you look on with your intelligence, not emotion.

In other words, you can only laugh at things from which you are detached.

You can’t laugh at that!

Bergson’s theory of intellectual comedy is the reason why few people laugh at a funeral. The mourners are simply too emotional. A bereaved and grieving family member will not find a funeral funny, because “every event would be sentimentally prolonged and re-echoed” for them. Where there’s sadness, there’s little room for comedy.

Some people, though, might not be as emotionally connected with the departed. Others might simply not feel the “right” emotional response. In these cases, are they allowed to laugh? Is it ever wrong to laugh at a funeral? If we believe Bergson, when we laugh at a thing, we declare it to be emotionally irrelevant. To do this at the death of a father, son, friend, or wife is simply cruel — regardless of your own sentiment. When we laugh, we are saying to the mourners, “Your source of grief is unimportant and a joke to me.”

It’s hard to find an ethical theory, outside pure hedonistic egoism (where only my pleasure matters), that justifies laughing at a funeral. With “greater good” theories, it almost always would create more misery than pleasure. For those who subscribe to the Golden Rule (“Do unto others as you’d have them do unto you”), few people laughing at a funeral would appreciate others laughing at the death of their own loved ones. For “virtue based” theories, it’s hard to see what admirable virtues laughing at funerals develops — it’s mean, callous, and cold-hearted. Aristotle would not laugh at a funeral.

I’m the kind of guy who laughs at a funeral

The problem is that laughing at this or that specific funeral comes too closely to laughing at the grief of those present. But could a case be made for laughing at “death” more broadly?

This is exactly what the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche saw in laughter. When we ridicule something, we diminish or deflate it. It is why despots around the world hate people laughing at them. It makes them look small. Nietzsche, in his work, The Gay Science, believes this is exactly the balm necessary in the face of a meaningless world. He argued that only with explosive gaiety can we give light to the darkness. For Nietzsche, laughter is the greatest medicine and weapon we have by which to take on “abysmal thoughts.”

If we focus only on the unremitting pointlessness of the universe — death and the grave — we languish and wither in the long winter of the soul. But, when we realize that true wisdom does not seek to find meaning or significance where there is none, and when we focus on simply living life, then the springtime wind brings the thaw. A laughter, a gaiety, a joie de vivre comes over us as we realize that the secret of life is not to fear or elevate death.

As Nietzsche wrote, laughter is “really nothing but an amusement after long privation and powerlessness, the jubilation of returning strength, of a reawakened faith in a tomorrow and a day after tomorrow, of a sudden sense and anticipation of a future, of impending adventures, of reopened seas, of goals that are permitted and believed in again.”

Laughter is living — it’s the recognition that nothing is serious enough not to be worthy of a good joke.

Jonny Thomson runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.