Are you morally obliged to pick up litter in your neighborhood?

- The bystander effect is a well-researched phenomenon where people will not involve themselves in a bad situation in order to help another person, regardless of the scale.

- This raises philosophical questions about moral responsibility. When we examine our attitudes on litter, we should consider the extent to which we’re to blame for the accumulation of litter in our communities.

- In Japan, picking up litter is much more ingrained in the culture. Why do people in other cultures think it’s okay not to pick up litter, even though we know it’s wrong, unsightly, and bad for the environment?

In some situations, it’s not easy to determine who’s morally responsible. Take an ostensibly black and white case, such as a person who intentionally stabbed and killed another person. On this fact alone, we might say the stabber is responsible for their actions. But ethical responsibility is a slippery beast. Let’s introduce some complications to the scene:

- Julia, a qualified doctor, saw the victim bleeding out but didn’t want to ruin her new suit. She carried on walking.

- Charles saw the killer pull out his knife but did nothing. He didn’t even warn the victim.

- John was the shop owner who sold a knife to the visibly twitching, unstable, and swearing murderer.

- Clare was the social worker who knew the murderer had violent tendencies and spoke often about killing.

At what point do we cross the line of ethical responsibility? Every one of these actors is responsible to some degree, but who is morally culpable? Who could we, or should we, blame? Who can we take to court? We all live in a sprawling, interconnected mesh. No event happens in isolation, and no action is straightforward.

One of the more relatable, and topically pressing, issues surrounding moral responsibility is litter, neighborhood, and social responsibility. Where, exactly, does responsibility lie?

Not in my back yard

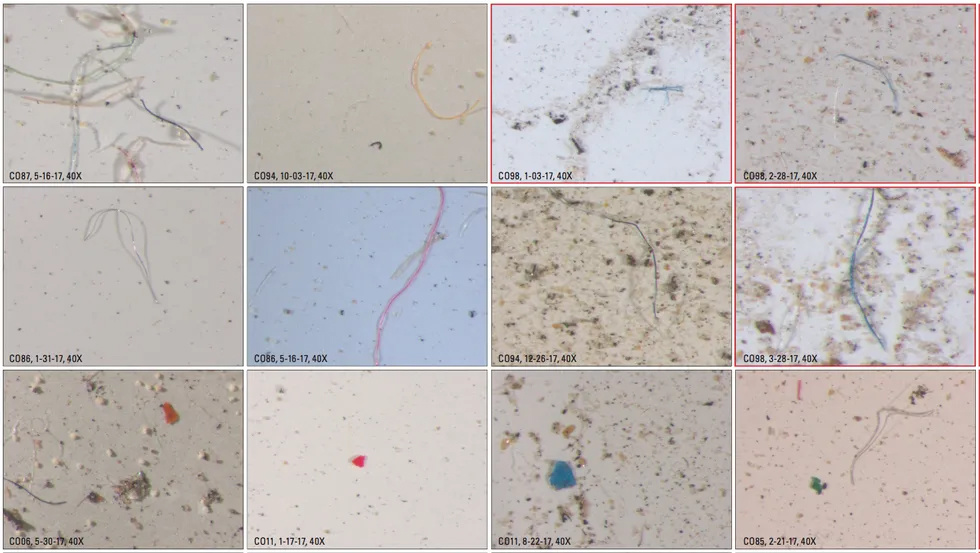

According to a new study from the University of California, most of the trash that people drop was purchased within two miles from where it was discovered. In other words, people are likely to drop litter in their own neighborhoods. The study looked at seven sites, finding that one of the most useful (and common) pieces of litter was receipts. These receipts are not only commonly thrown away, but they often come with time and location markers, making it possible to tell where the litter came from.

The study raises interesting ethical questions about the nature of litter. Most people would agree that each of us is responsible for not littering and disposing of our trash properly. But to what extent are we responsible for the litter we see, dropped by others, especially that which is found in our local area?

A lot of research has gone into the so-called “bystander effect” — where many people walking or standing by will not get involved to prevent an immoral action taking place. As a 2018 meta-analysis says, “this pattern is observed during serious accidents (Harris & Robinson, 1973), noncritical situations (Latané & Dabbs, 1975), on the Internet (Markey, 2000), and even in children (Plötner, Over, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2015).” Humans tend to ignore or avoid getting involved in matters that “don’t concern them,” regardless of the severity or wrongness of that action. It is unsurprising, then, that we treat litter in the same way.

The Japanese approach to litter

Our attitudes toward litter depend partly on the culture we’re born into. Some people will remember when, after their 2018 World Cup game against Columbia, the Japanese fans stayed behind to clean up. They came equipped with large plastic bags in which they meticulously collected the trash in their seats and rows. It’s hard to imagine American or European fans doing the same.

From a young age, Japanese children are often taught to tidy up not only their households, but also community spaces like their schools. It’s not uncommon for schools to be entirely swept clean by the students rather than hired adults. Japan has a deep cultural history of paying attention to detail. It’s seen in sado, the tea ceremony, and kado, the practice of arranging flowers. In part, this all stems from certain meditative and mindfulness elements in Buddhism and Shinto. But, more than that, it also has to do with respecting the community, and accepting responsibility for your part in the whole. You are responsible not only for your own tidiness and cleanliness, but also for those close to you, as well as your wider community.

This sense of respect and pride in your community is not something utterly alien to everyone else. We have street-wide Christmas light displays, neighborhood watch programs, and even roads with matching color schemes. What’s more, many local, community groups will organize litter clean-ups to help the community. We force convicts to do “community service” schemes, which invariably involve sprucing up the neighborhood.

A whole litter mess

So, what moral responsibility do we have to clean up others’ litter? On the one hand, we were not the ones who littered in the first place, and so we are not culpable for the damage done. But there is also such a thing as immoral inaction. Doing a wrong and letting a wrong continue might be of a different magnitude, but both still possess an element of moral responsibility. In our opening example, Julia the doctor walked by without helping and is, to some degree, responsible for the death of the victim. She saw something wrong and ignored it.

Are we all not equally to blame for litter that we ignore? If we assume littering is wrong, then every time we do not pick up trash, we are also taking at least partial responsibility for the wrongness. We pay taxes and have professionals tidy our streets and neighborhoods for us. But this does not absolve us of this responsibility. We are each responsible for our inability to make something better, as much as our ability to do wrong.

Jonny Thomson runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.