Why are Americans still afraid of atheism?

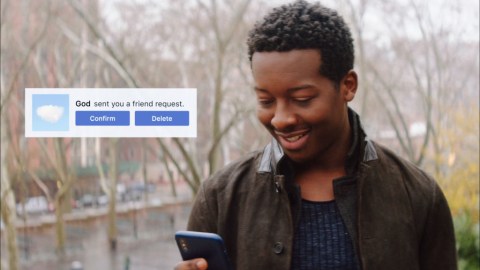

NEW YORK - MAY 10: GOD FRIENDED ME stars Brandon Micheal Hall (pictured) in a humorous, uplifting drama about Miles Finer (Hall), an outspoken atheist whose life is turned upside down when he receives a friend request on social media from God and unwittingly becomes an agent of change in the lives and destinies of others around him. (Photo by Jonathan Wenk/CBS via Getty Images)

- 51 percent of Americans would not vote for an atheist president.

- Though America wasn’t founded as a Christian nation, religion has always had a strong influence.

- It wasn’t until the 1950s when religion gained its current prominence in the national imagination.

America’s religiosity is not as clean-cut as advertised. While we were certainly not founded as a “Christian nation,” Dionysian chaos didn’t reign supreme either. It wasn’t until the 1930s that an equal protection clause was invoked to guarantee religious liberty and separation of church and state — it had been proposed 140 years earlier by James Madison.

Previous literature espoused faith, however. For example, the 1781 Articles of Confederation mention a “Great Governor of the World.” By the time the Constitution rolls around the writers left aside a creator for the more ambiguous “Providence.” It was in the 19th century that tent revivals brought fire and brimstone back to Northeastern suburbs; the South soon followed suit.

The idea of a deity fit tobacco and cotton cultures well, as Susan Jacoby writes in Freethinkers, “The expanding white southern homogeneity and hegemony of faith in an infallible God led inevitably to a moral and a utilitarian justification for slavery.”

The reality is that Americans have wavered in their faith for centuries. Some were always religious, others not so much. Sometimes religion takes the lead, at others it sits quietly in the background, our attention fixated on another shiny object. If we must point to a period that truly framed our modern pivot toward religion, we need look no further than the 1950s, when an incredible amount of it was injected into the public imagination. As Casey Cep writes in a recent New Yorker article,

Two centuries after the Founders wrote a godless constitution, the federal government got religion: between 1953 and 1957, a prayer breakfast appeared on the White House calendar, a prayer room opened in the Capitol, “In God We Trust” was added to all currency, and “under God” was inserted into the Pledge of Allegiance.

The modern notions of American exceptionalism and manifest destiny, though not dreamed up during this decade, certainly gained a loyal following, considering we’re still towing that line. You can barely go a day without hearing some pundit or politician remind us that “America is the greatest nation in the world,” which is often a dog whistle for the Religious Right; what isn’t said but is implied: “because God said so.”

This isn’t true of everyone claiming America to be a great nation. Plenty of immigrants rightfully repeat this mantra after escaping harrowing conditions elsewhere. Yet for a majority of Americans, “greatest” and “God” go hand-in-hand. Such nationalistic sentiments do stoke the anger of a longstanding tribe of believers. However, while migrant caravans are only scary during the week leading up to an election, atheists are always frightening.

Richard Dawkins in Sydney, Australia. Photo credit: Don Arnold / Getty

As Cep writes, pinning down a definition of atheism is impossible. The “new atheists” are generally myopic in their views on divinity, focusing on scriptural fallacies. The lines are more blurred in Buddhist and Taoist traditions, where the lack of a creator god doesn’t dispel all forms of mysticism. Though the modern secular Buddhist movement might not fall prey to demon gods and dozens of hells, there are entire continents of believers that do.

So we have to wonder if America’s fear of atheism is truly an existential crisis or simply falls into the category of “other.” Most people I know don’t fear Shintoism because they have never heard of it, whereas “atheist” fits neatly into a package of disbelief. While atheists and “nones” are on the rise, most Americans won’t even consider an atheist president, as Pew reports.

The new survey confirms that being an atheist continues to be one of the biggest perceived shortcomings a hypothetical presidential candidate could have, with 51 percent of adults saying they would be less likely to vote for a presidential candidate who does not believe in God.

Let’s look at the issues that matter less to voters than atheism: smoking marijuana, being gay or lesbian or Muslim, extramarital affairs and financial troubles. I agree that none of those should be a problem, though the latter two are tied into a peculiar crisis of disbelief that Evangelical Republicans are currently having with the president. Trustworthiness should be a more important quality in choosing a leader than metaphysical beliefs, but, well, here we are. As Cep concludes,

In the end, the most interesting thing about a conscience is how it answers, not whom it answers to.

The big, scary atheist is about as dangerous as Ecuadorian refugees walking a thousand miles in hopes of asylum so their children won’t be killed. Both of these failures of imagination are dangerous. One is politically expedient, the other chronic. That’s a shame. Actions matter more than beliefs. Until we learn that lesson, we’ll keep falling for the same old tricks.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.