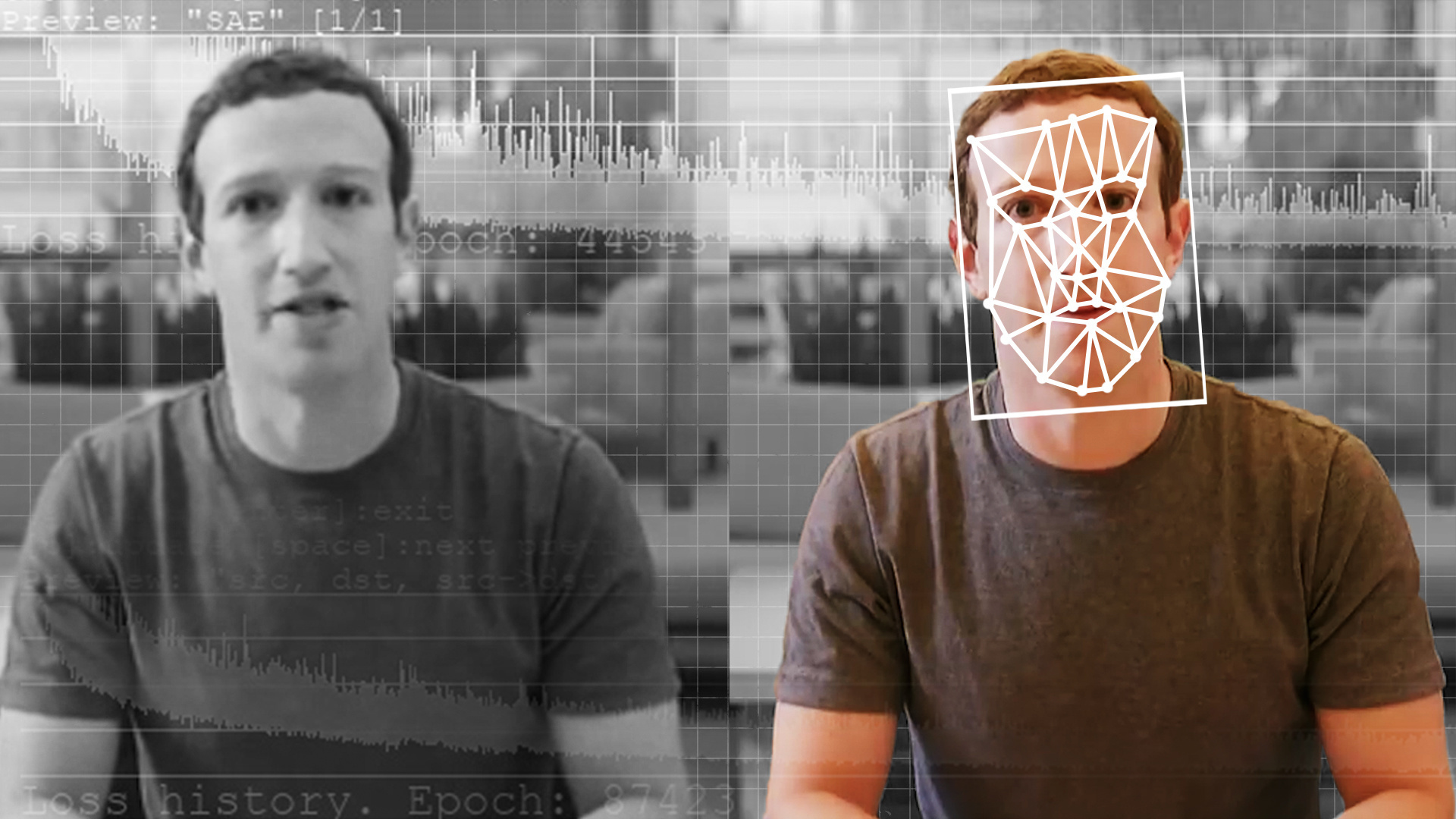

Deepfakes: When is it morally wrong to alter videos?

- We now have easy-to-use technology that can live-edit footage and make Hollywood-quality deepfakes.

- Many AI industry leaders will wipe their hands of responsibility, arguing that you shouldn’t fight progress or blame manufacturers for users’ misuse.

- Yet, there are reputational and legal issues at stake. Being trusted and producing accurate content still matters to many people.

When an actor gives a breathtaking performance, can someone else “improve” it with digital editing? Are there ever cases where a movie being “digitally enhanced” might aesthetically ruin the experience? A lot has been covered recently about the explosion of AI technology, and how it’s encroaching — or even transforming — entire sectors. Video editing is no exception.

In a recent tweet, the visual effects artist Daniel Hashimoto experimented with using new NVIDIA technology on the award-winning TV show The Bear. Hashimoto had the AI change the eyes from pointing down to looking at the camera. The main character was no longer looking into the distance, but rather at you. It’s a small thing, and might not matter to most people. To others, however, it completely damages the effect of the scene. It does not improve things but reduces and warps the artist’s intent.

Remixed

In January 2023, the UK television network ITV brought us the first ever TV “deepfake comedy”: Deep Fake Neighbour Wars. The premise is that we meet a crew of sofa-loving TV addicts, who bicker constantly with their neighbors. The twist, though, is that the entire street is made up of A-list celebs. There’s Nicki Minaj shouting down Tom Holland; Rihanna fighting Adele. It’s pretty funny, as comedy goes, but it raises an interesting question about the future of deepfakes: To what extent should we allow people to manipulate what we’re seeing?

With Deep Fake Neighbour Wars, you’re told straight away these are fakes (and, I’m assuming ITV has some kind of legal team). But what Hashimoto did with his NVIDIA tech is an example of something more insidious — it happened without the consent of those involved. The YouTuber, Kelsey Brannan (Premiere Gal), explains some methods by which AI can manipulate footage in a great explainer. She explains how AI can remove objects and people from video, how it changes a background, or how it can remove sound or a voice. Teams like Runway are capable of editing videos in real-time, and doing so with compelling realism (it’s a bit like having those Facebook filters that make you look like a dog — but with Hollywood quality).

As with any disruptive technology, we are all going to adapt to this new world. Ethicists, lawmakers, and digital consumers of all kinds will have to work out how to deal with a world where video — live video — might not be as it seems. A recent paper from a team at Carnegie Mellon University, USA, studied the ethical issues surrounding video editing — especially, deepfake — technology. They did two things. First, they asked many industry leaders and companies in AI video technology what they thought their responsibilities were. Second, they asked what factors might limit or establish boundaries for those leaders.

The responsibility of developers

What ethical duties, then, do AI developers feel they have? According to Gray Widder et al., the answer is, “not many.” In general, AI industry leaders present three arguments:

The first is the “open source” argument. This is where a program is either made free to use or the source can be copied and used by other programmers (as an API, for example). As one AI leader put it, “Part of being open-source Free Software is that you are free to use it. There are no restrictions on it. And we can’t do anything about that.”

The second is the “genie’s out of the bottle” argument. In other words, this is the idea that if we don’t do it, someone else will. Technology is inevitable. You cannot stop progress. Once AI is “out there”, you can’t then somehow reverse it. Short of some nuclear apocalypse, technologies never go away. AI video editing is here, so let’s deal with it.

The third is the “don’t blame the manufacturer” argument. If someone uses a tool for nefarious means, that’s on them, and not the tool makers. If someone writes an antisemitic book or draws a racist picture, or plays a hateful song, you don’t blame word processors, pencils, and guitars. When someone makes deepfake porn or spreads misinformation, that’s their crime, not the AI programmers’.

What would hold back video editing?

All are pretty compelling arguments. The first, perhaps, could be rebutted. Creating open-source programs is a choice — a libertarian philosophy (or a money-making/PR decision) of coders. Access could be restricted to certain tools. But the second and third arguments are well made. Those who try to fight progress are often doomed to fail, and tools are not, in themselves, morally blameworthy. What, then, is needed to prevent a future flooded with malicious or misleading deepfakes? The paper from Carnegie Mellon University highlights two answers.

First, there are explicit ethical lines to be drawn, namely: professional norms and the law. Unofficially, a culture of certain standards could be engineered; we create industry stigma or acceptable use standards. As one leader said, “We follow things like […] various journalism association standards and normal things you would follow if you’re a Washington DC political correspondent.” But officially, there is an obvious red line in video editing: consent. If you don’t agree to your image being used or manipulated, then it’s wrong for someone to do so. It’s a line that can be (and has been) easily turned into law — if you deepfake someone without their consent, then you risk a criminal charge. The illegality would certainly limit (if not stop) its use.

Second, there’s a reputational issue here. Most people, most of the time, don’t like being duped. We want to know if what we’re seeing is accurate. So, if we find out a website regularly features deepfakes, we’re less likely to see them as reputable. If, on the other hand, a website calls out deepfakes, promises never to use them, and has software and oversight on their use, users are more likely to trust, use, and pay for them. Deepfakes might get a laugh, but they don’t get a good reputation.

The world of video editing

So, the genie is most certainly out of the bottle, and the Internet Age is giving way to the AI Age. We’re all left blinking and bemused at this bright new dawn. Yet, the world will adapt. Societies will find a way to bring these technologies into human life with minimal disruption and maximal advantage. As we’ve done for millennia, we’ll keep doing human things alongside or with AI as tools. There’s nothing world-ending about the AI Age.

But we do need to consider which rules and norms ought to be established. We are in the calibration period of a new age, and the way we act now will define generations to come. Like the leaders of a revolution just won or frontiersmen facing a new land, there’s something to be built here. And it should be built with ethics and philosophy in mind.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy at Oxford. He runs a popular account called Mini Philosophy and his first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.