Across all ages and nearly all areas of education, boys are under-performing girls.

“Girls are about a year ahead of boys in terms of reading ability in OECD nations, in contrast to a wafer-thin and shrinking advantage for boys in maths. Boys are 50 percent more likely than girls to fail at all three key school subjects: maths, reading, and science,” Richard Reeves, a senior fellow in Economic Studies and the Director of the Future of the Middle Class Initiative, wrote in his recent book Why the Modern Male is Struggling,

According to a 2018 Brookings Institution report, about 88% of American girls graduated high school on time, compared with 82% of boys. In 2020, six out of ten college students were women. Once on campus, they graduate at higher rates, receiving more associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in the process. As evidenced by declining college enrollment in the U.S., a drop for which men account for 71%, the gender disparity is continuing to worsen.

The reasons for this expanding educational divide have been vociferously debated and discussed. A startling shortage of male K-12 teachers (just 24%), the hands-off, tedious structure of school, and poor parenting are a few of the explanations offered. Another, less frequently discussed, is starting to emerge from the scientific literature: Boys appear to be graded more harshly than girls.

Watch our interview with Richard Reeves:

Boys vs. girls

When researchers across the world — from Israel and Sweden to France and Czechia — explored teachers’ grading behaviors, either by having educators grade hypothetical students’ identical works while only changing the students’ gender, or comparing grades achieved by “similarly competent” male and female students, they found that girls consistently receive higher grades than boys.

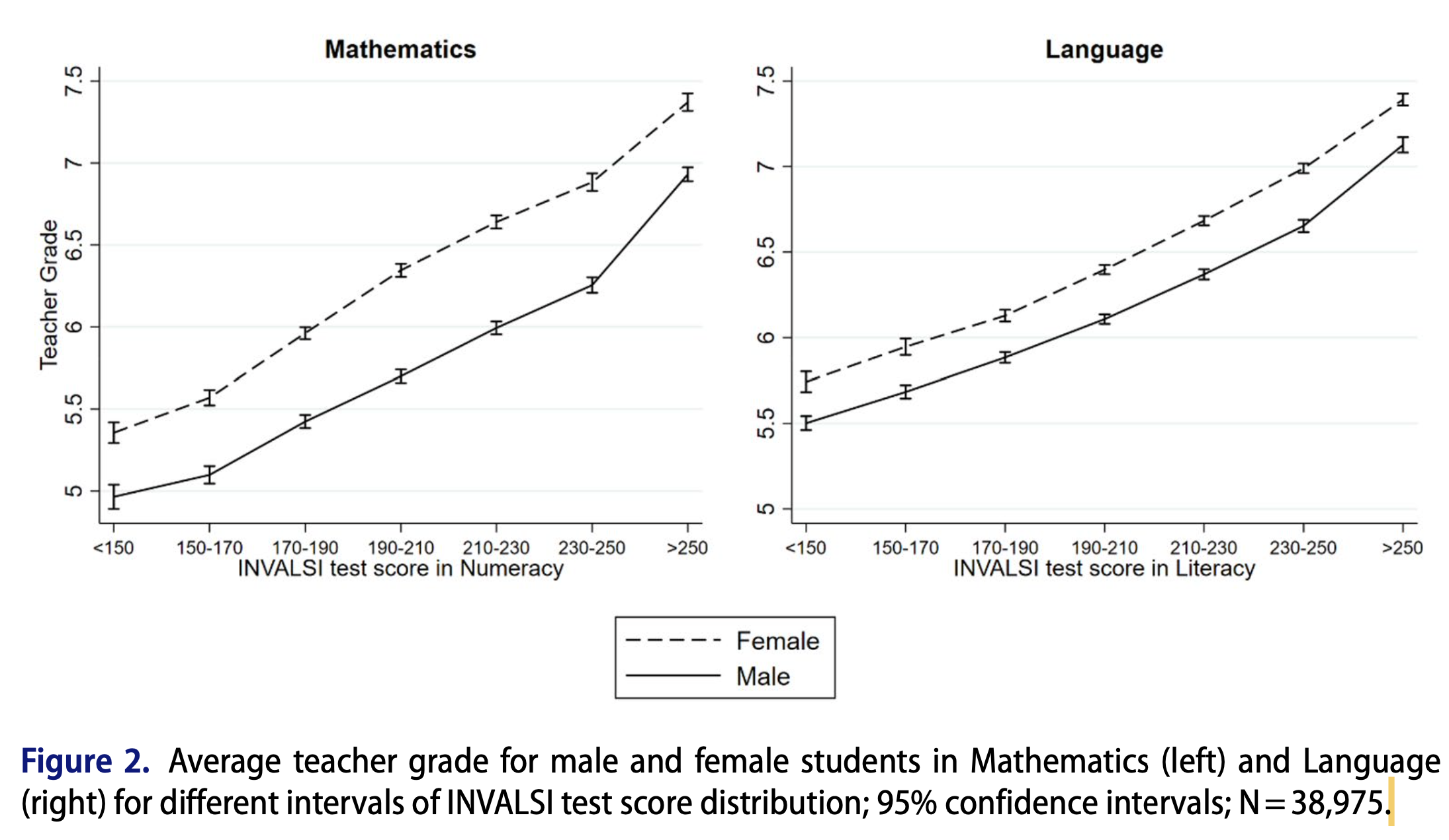

Further cementing this pattern is a recently published study conducted on nearly 39,000 10th grade students in Italy.

Authors Ilaria Lievore and Moris Triventi, both in the department of sociology and social research at the University of Trento, found that for students with the same level of “subject-specific competence,” as measured by standardized test scores, girls are graded more generously than boys. In Italy, students are graded on a one to ten scale, with six being a passing score. In mathematics, girls are graded about 0.4 points higher than similarly competent boys. In language, the gender grading premium is 0.3 points in favor of girls.

Since the researchers also procured data on students’ teachers and classroom characteristics, they explored whether the teacher’s gender or the classroom size had any effect on the difference in grading. Alas, they didn’t see any sign that male teachers were kinder graders to boys. Moreover, fewer students in a classroom did not mitigate the effect.

The researchers were thus left to speculate about the cause of the grading imbalance.

Teacher bias?

“One related theoretical stream interprets gender grading mismatch as also being a function of students’ observed behaviours,” they wrote. “School and classroom environments might indeed be adapted to traditionally female behaviours. Female students might thus adopt such actual behaviours during class, including precision, order, modesty, and quietness, which go beyond the individuals’ academic performance, but which teachers may highly reward in terms of grades.”

The simple fact is that, despite their best intentions, teachers can be swayed by the same unconscious biases as the rest of us. As one anonymous teacher pointed out on Reddit, “Teacher’s mood plays into grades. How the student acts in class affects grading. How the students’ parents act plays into grades.”

Thus, a simple solution to grading-related bias is for students to write their names at the very end of any test or assignment, so the grader only knows their identity after scoring the work.