Beauty bias: We tend to think pretty people are morally superior

- Beauty is often associated with goodness.

- Studies suggest that people make major decisions based on how attractive other people look.

- A new study suggests this may be because we assume positive moral traits are tied to good looks.

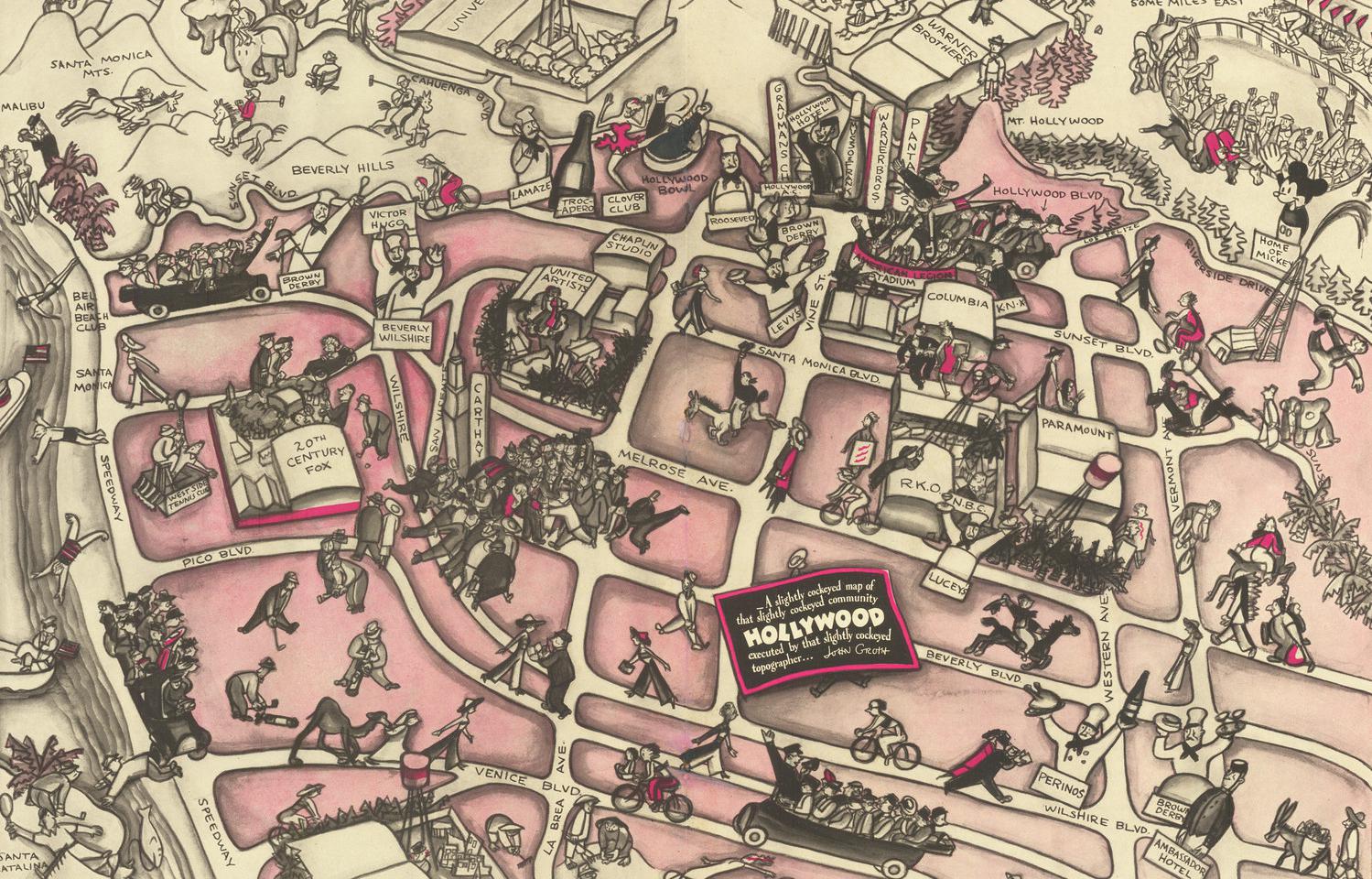

Humans have always associated beauty with goodness. Philosophers like Socrates and Kant made the connection, and even a glance at some of the more famous morality pieces shows that many artists assume that you already know that beautiful people are good, while the wicked are hideous. One story from Ancient Greece even suggests that a woman who was on trial for impiety, Phryne, used her beauty to argue that she was favored by the gods and therefore could not have committed the crime. She was acquitted.

The prevalence of the assumption that beautiful people are good has been studied for the past few decades, with extensive research on the subject going back to the 1970s. The research shows that people are more likely to assume a beautiful stranger possesses traits like warmth, sincerity, and generosity. The good-looking are also presumed to be smarter, saner, more sociable, and generally higher functioning.

Before you start thinking that you’d never judge somebody by how they look, the studies suggest that you likely do it all the time — very quickly and not fully aware of it.

This bias has real-world impacts. The attractive are less likely to be found guilty by simulated juries and more likely to get reduced punishments when they are. People tend to vote for more attractive politicians, promote better-looking underlings, and even give more attention to better-looking children than those with — as George Carlin put it — “severe appearance deficits.”

A study recently published in the Journal of Nonverbal Behavior took a close look at which traits we associate with beauty, shedding little light on why we possess the beauty bias.

How to get people to show their biases

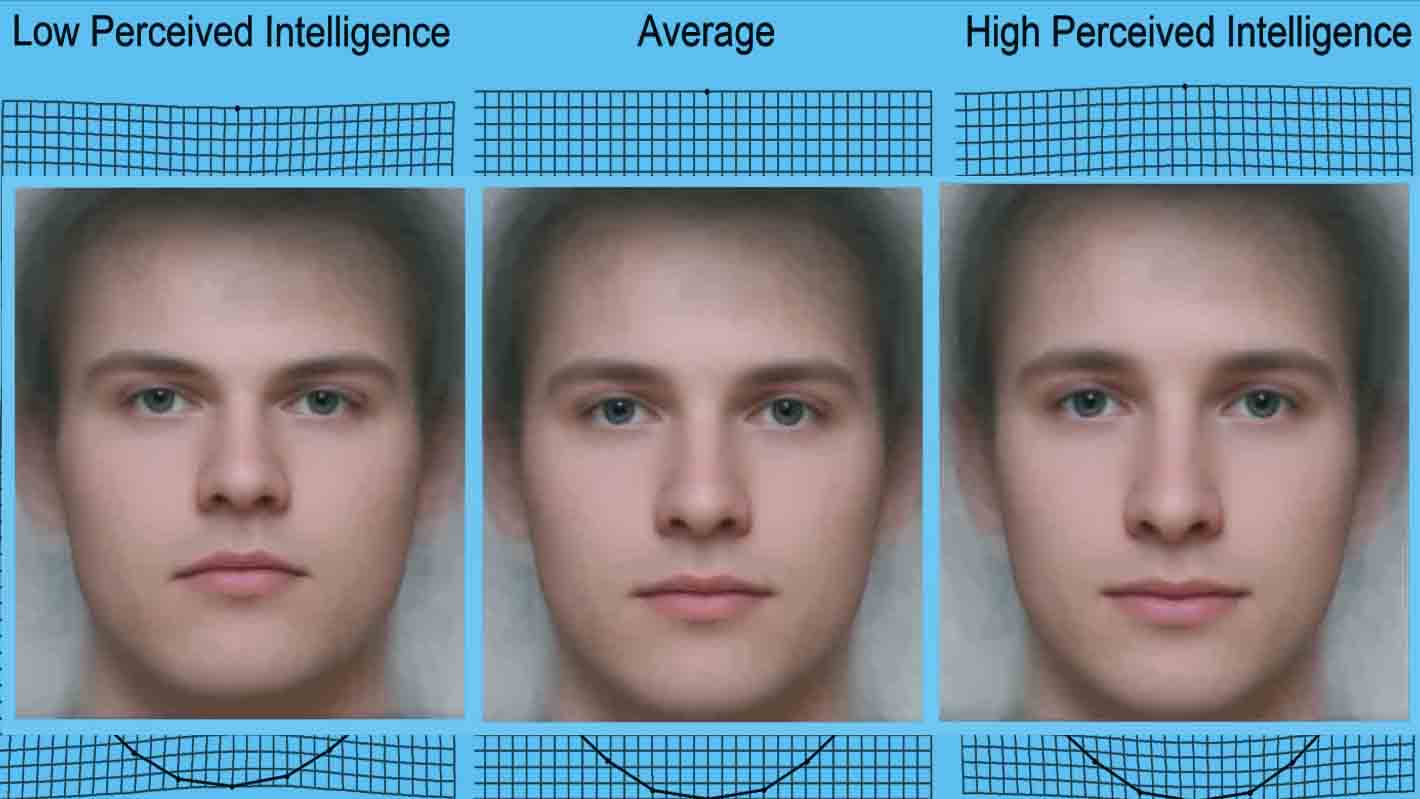

To carry out the study, the authors asked participants to look at images of faces and then had them decide whether the person possessed a given trait, such as being sympathetic or generous, to a greater or lesser degree than the average person.

This study differed from previous studies because it not only looked to see whether people associate positive traits with good-looking people (we know they do), but also took a closer look at which traits are associated with appearance. The first part of each test focused on purely moral traits, such as being fair, trustworthy, or honest, while the second part examined positive but non-moral traits, such as being funny, organized, or calm.

The first test used traits previously used in a 2004 study when asking the questions and involved 504 participants who looked at either six images of attractive people or six images of unattractive people. The participants were then asked to rate how likely it was that the depicted person had more of a given trait than the average person.

The second test, involving 756 participants, was very similar to the first, but it included different language to make sure the results of the first test were not tied to the exact terms used.

The results of both tests lined up with previous studies showing that people associate beauty with all manner of positive traits. However, the recent tests shed new light on which traits are most affected by the “halo effects” that good looks provide. In both studies, moral traits were more likely to be associated with beauty than non-moral traits. The effect was particularly notable in the second study, in which beautiful people were 20% more likely to be perceived to have these traits than the average person, compared to only a 10% increase in the perceived likelihood they would have the non-moral traits.

While all of the test subjects were American, limiting how much the study can be generalized, similar tests have been carried out in other cultures suggesting that this effect — if not the exact manifestation reported here — is universal.

What does this mean for how the world works?

The authors of the study noted that they expect their findings to have real-world implications. Given how many previous studies demonstrate that there are serious consequences from this bias, their stance should not surprise us. They pointed out, however, that despite the long history of science knowing that this bias exists, “there is no intervention available that may reduce prejudice toward or discrimination against unattractive individuals.”

They went on to argue that future research “should develop psychological or social interventions that may help to counteract our bias to utilize information about others’ attractiveness in moral character evaluation and as a result, reduce prejudice and discrimination.”