7 Greek philosophers and their brilliantly flawed explanations of nature

- The Greek philosophers pondered everything, but some really wanted to know what the world was made of.

- The search for the arche — the first principle — led to the invention of many key ideas in philosophy.

- In the end, the Greeks made major advances, even if they were all ultimately incorrect.

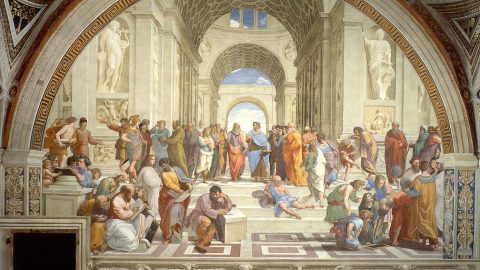

The ancient Greek philosophers produced a vast array of ideas. While thoughts on how to live occupied much of their attention, they also wondered exactly what constitutes the world around us. It doesn’t matter that many of their conjectures turned out to be several leagues wide of the mark — they still blazed a conceptual trail for humankind and our attempts to understand the nature of reality.

Thales: Everything is water

For Aristotle, Thales was the OG: the very first philosopher. Living in Miletus — an ancient Greek city located in modern-day Turkey — during the 6th century BC, Thales is known for his work in philosophy, astronomy, and mathematics.

He also attempted to explain the origin of all substances, deeming water the arche — the first principle from which all others followed. He maintained that water would transform into other substances, and all substances could revert to water. In retrospect, Aristotle (384-322 BC) offered several reasons Thales might have selected water, most of which are simple observations about how life requires water and how the substance can transform from one state to another. It is thought that Thales also argued that the Earth was a sphere that floated on a sea of water. The occasional shifting of the planet in this sea, he reasoned, was the cause of earthquakes.

Aristotle tells us Thales was the first named individual in the history of Greece to be unsatisfied with mythological explanations of the world around him, and then tried to offer alternatives through reasoning. Regardless of his misguided notion that earth could arise from water — which was scientifically disproved as late as 1768 — Thales deserves our lasting admiration for starting a long tradition of trying to explain the world rationally, using only observable evidence.

Anaximander: The endless aperion

A contemporary (and likely student) of Thales also living in Miletus, Anaximander was the first Greek philosopher to have written his ideas down. He also advanced what might be considered the first philosophical arguments for his position in contrast to Thales’ empirical observations. He is also said to have made the first map of the world known to the Greeks.

Anaximander looked at the four classical elements — water, air, fire, and earth — and argued that none could be the arche. These elements were limited, finite, and tended to cancel each other out. Instead, he proposed a new substance called the apeiron, which translates to “the unlimited” and was supposed to be infinite.

He also theorized about the cosmos. Anaximander was the first to argue that the celestial bodies made full circles as they moved through the night sky, a major step forward in astronomy. Furthermore, he argued that the Earth was floating in empty space and that the celestial objects we see were not all equidistant — essentially inventing the concept of outer space.

While these ideas have outlived their usefulness, several were major advancements — he more or less originated philosophical arguments that thinkers like Aristotle and Plato would later refine.

Anaximenes: Everything is air

The last of the great Milesian philosophers, Anaximenes is recorded to have worked and likely studied under Anaximander. He moved away from his teacher’s idea of a separate substance that became the elements we interact with, and proposed that air was the arche. He implied that air was semi-divine and possibly infinite in scope.

Unlike his predecessors, however, he also laid out a theory for how this worked. First, he proposed that condensed air cools and becomes water and earth. When diluted, air warms up and becomes fire. He even pointed out that this could be tested by blowing on your hand with either a wide or narrowly opened mouth. Next, he associated heat and dryness with rarefying air, whereas moisture and lower temperatures were related to condensing air. Then, turning to the cosmos, he posited that air was also the foundation of the stars, which operated just like burning objects on Earth.

With his proposals, Anaximenes introduced into Western thought the idea of an empirically backed theory of transformation that can be discussed and tested. His 2,000-year-old notion that the laws of nature apply in the cosmos just as they do on Earth was proven by Isaac Newton in the early 18th century.

Heraclitus: Flux and fire

Heraclitus was a philosopher from Ephesus (like Miletus, in modern-day Turkey) who lived in the 6th century BC. While his work was likely a response to the Milesian philosophers, he isn’t thought to have studied with them. In his writings, only fragments of which survive, he said that the world has always existed and is based on “ever-living fire,” and that everything is constantly changing.

Heraclitus introduced a system by which the elements transform into one another, however misguided the details appear to the contemporary mind. For example, he explains: “The turnings of fire: first sea, and of sea, half is earth, half firewind.” Furthermore, he maintained that this process can also work backward and that the proportions of matter are maintained.

He argued that the Universe is in constant flux, with nothing ever the same for more than a moment. A quote attributed to Heraclitus — “No man ever steps in the same river twice” — is deceptively profound and has significant implications for the usefulness of empirical knowledge.

Parmenides: The world of unity

A philosopher from Elea (a Greek colony in modern Italy) around the year 500 BC, Parmenides is perhaps the greatest of the pre-Socratic thinkers. Traditionally named “On Nature,” his masterwork was an 800-verse poem on the nature of reality, in which he argues that the world we see is an illusion. The real nature of the world is unavailable to our senses but accessible to us through reason. Furthermore, this “real” world is unchanging, unified, and timeless.

His arguments begin with the idea that we cannot have a rational concept of “nothingness.” Since nothingness can’t exist, he held there was no empty space. (Quantum mechanics has shown this to be correct.) Without empty space to move into, he maintained motion was impossible. He continued in this way until he refuted the ideas of change, difference, and ending. He then turned to the world we interact with, explaining it as mere appearances.

His influence on Western thought has been substantial, particularly through Plato. Zeno, the famed maker of paradoxes, supported Parmenides’ ideas, which continue to influence the philosophy of time. His proposition that our senses are useless when looking for truth has proven enduring. (Immanuel Kant made a similar argument.) Other pre-Socratic philosophers had to engage with his ideas to be taken seriously.

Democritus: Atoms

Born in Abdera (an Ionian colony) in 460 BC, Democritus was a prolific author who wrote on everything from ethics to botany. Although we have only what others say about him to go on (none of his work survived), it is clear that he was among the first thinkers to propose the idea of an atom.

Democritus, or perhaps his teacher Leucippus, laid out a theory called “atomism.” He argued that it was impossible to divide matter infinitely, as there must come a point where something can no longer be divided in half. Then, you have an atomos, meaning “not divisible.”

The atoms, which he argued move through empty space, build up the entire world based on their shape, arrangement, and position at a given time. The qualitative features of the world are not inherent to atoms, but are caused by the interaction of the atoms that make up external objects and the ones that make up our bodies.

Greek atomism was entirely speculative — it wasn’t until the early 19th century that physical evidence for atoms was produced — and Democritus earned the respect of those who disagreed with him. Among them was Aristotle, who praised Democritus for his reasoning ability while rejecting atomism. The idea would be revisited centuries later when thinkers like Galileo and Descartes explored similar philosophical territory.

Plato: The Forms

Working primarily in Athens during the 4th century BC, Plato remains a towering figure among philosophers. His thinking went beyond the ideas of his teacher, Socrates, and influenced essentially all subsequent Western and Middle Eastern philosophy. In addition, he founded the Academy in Athens, where many great minds studied, including Aristotle.

Plato wrote on many subjects, including metaphysics. His Theory of Forms was based on pre-Socratic ideas. He argued that the world in which we live is an imperfect copy of the world of “Forms”: the unchanging, non-physical, enduring essences of all things. Everyday objects, like chairs, are flawed reproductions of the “Form of chairness.” The same is true of everything that exists in the physical world.

Plato argues (like Parmenides, to some degree) that the foundational element of reality is mathematical and idealistic. He agrees with Heraclitus that the world we interact with is always changing, and he borrows ideas on how the elements could transform into one another — and what those elements are — from the Milesians.

Significantly, Plato opened his own theory to question. The Dialogue Parmenides, which depicts a fictitious meeting between Socrates and Parmenides discussing the Forms, appears to show either his rejection of the theory later in his life or the need for revisions to it.

Plato’s legacy remains incomparable. Alfred North Whitehead put it best: All Western Philosophy is a series of footnotes to Plato.