Why apocalyptic fantasies appeal to us psychologically

- In his new book, The Next Apocalypse: The Art and Science of Survival, author and archaeologist Chris Begley compares our modern conceptions of apocalypse with historical examples of societal collapses, arguing that the two are quite different.

- This excerpt of the book explores how popular culture depicts apocalyptic scenarios, and why apocalyptic fantasies seem to be strangely appealing for many people.

- One reason apocalyptic scenarios appeal to us is that collapse presents us a chance to do things all over again — to be the heroes we cannot currently be.

Excerpted from The Next Apocalypse: The Art and Science of Survival by Chris Begley. Copyright © 2021. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

We have all thought about it. What would we do if everything came crashing down? We create varieties of narratives—some clearly fiction and some presented as our best guess about the future. The narratives we create become the reality we expect. These stories tell us a lot about ourselves, including what we want now, and what we hope for and fear in the future. Today, we seem to have reached new heights in the production of apocalyptic and dystopian narratives. Even a cursory examination of the apocalyptic media available to us reveals hundreds of films and thousands of books about dystopian futures. These are so popular that when I retitle my wilderness survival course as a “postapocalyptic survival” course, I get twice the interest. It’s been termed “apocatainment” by Gwendolyn Foster.

Media representations of the apocalypse certainly generate enthusiasm, but they can also limit the parameters of our thinking. Discourse matters, and everything from our vocabulary to the topics we choose to focus on can shape how we think about something, or even how we are capable of imagining it. The threats and fears presented in apocalyptic narratives are metaphorical representations of tensions that exist in the real world. From the critiques of racial justice to the xenophobia that underlies the narratives, nothing is merely about zombies, or a comet. The fear is not emanating from a virus, or a natural disaster, or at least not only from that. We see this play out in our recent experience with a pandemic. Our reaction to Covid-19 reflected ongoing political and cultural tensions, and the pandemic became a canvas painted by this struggle. As in the fictional apocalyptic narratives, the immediate threat became a cipher for an underlying concern.

There is a dark side to some of these fantasies. In some cases, the rhetoric that accompanies apocalyptic images promises a return to a traditional way of life, which sounds positive and conjures up wholesome images of satisfying, preindustrial, rural family life where hard work pays off. Of course, in the United States, that reality existed only for some groups. For most, the misogyny, racism, homophobia, and other “traditional” attitudes would make a return to the past overwhelmingly negative. The status quo ante of tradition is a more toxic version of the status quo, especially for those not protected by privilege. While broader contemporary society understands these ideas as backward and bigoted, a postapocalyptic world offers the opportunity to embrace them. These narratives inform how we think about the past, present, and future, and importantly, they influence how we act.

I am not conducting an exhaustive survey of apocalyptic literature here. The examples I discuss in the upcoming pages are ones that resonated with me as good examples of the kind of apocalyptic stories that I see as shaping our vision of the future. A few contemporary apocalyptic narratives stand out to me, either because of their place in the history of the genre (the book Lucifer’s Hammer, or the film Night of the Living Dead) or because they embody certain approaches or points of view (the book One Second After). There are a few that stand out as masterfully artful examples of the genre, such as Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road, N. K. Jemisin’s novel The Fifth Season, or the film Mad Max: Fury Road. There will be exceptions to any trend I identify, and I do not claim that the tropes I highlight occur in some particular percentage of narratives out there. In fact, that does not matter here. I am interested in the ones that make their way from narrative to real life, either in our actions or in our imaginations.

There are thousands of apocalyptic narratives. I am familiar with many of them, like most of us are, and I thought I had a sense of what was out there. I did not. I had barely scratched the surface. Some narratives paint a bleak and awful picture, like McCarthy’s The Road, in which the protagonist fights an impossible battle to shield his young son from rampant cannibalism, cruelty, and despair amidst a dead world. Michael Haneke’s The Time of the Wolf presents a similarly dark vision of the postapocalyptic world, in which a French family finds its potential safe-haven in their country home already claimed by hostile strangers, and after finding no help, and with nowhere to go, they wait on a train that might take them away from the chaos. Nobody would want those futures. They are bleak, hopeless, and lacking in compassion.

In many other cases, it is apparent that the thought of an apocalypse appeals to us on some level. Something about that imagined reality resonates with us, and we want some of what it offers. Perhaps this mirrors our experience with war movies, in which we present the hellish reality of war as an adventure story, a heroic epic. Perhaps we do the same to “the apocalypse,” sanitizing and romanticizing something that is inherently awful. A radical change, though, may not be inherently awful. Some things need to change, certainly. Perhaps the apocalypse becomes shorthand for starting over and shedding the burdens we have accumulated.

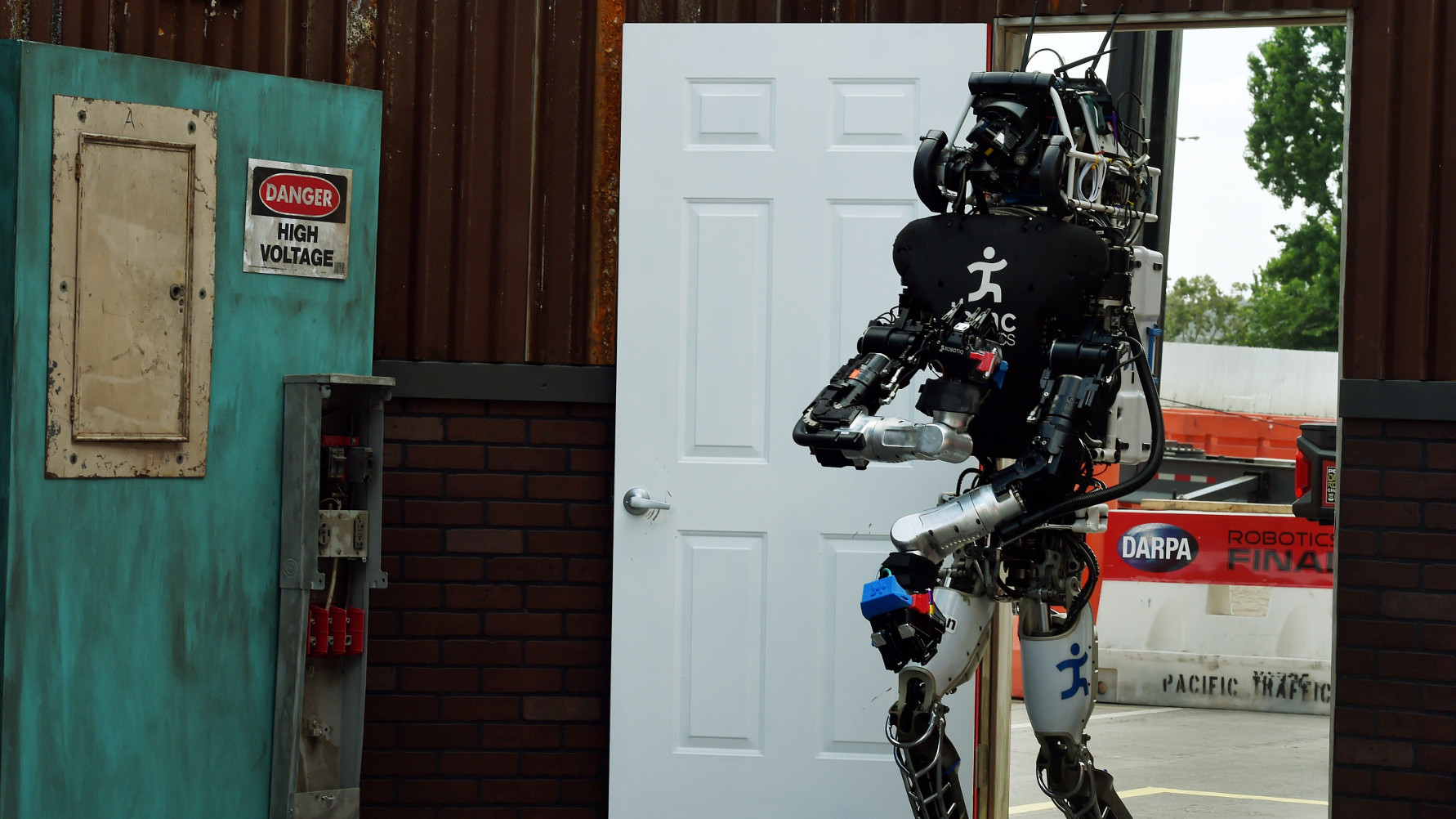

One thing is clear: future apocalyptic scenarios are not presented in the same way as the disasters that we actually experience. There is little appeal to the aftermath of a tornado, or a house fire. Our apocalyptic fantasies, however, alternately horrify and attract us. I cannot explain away the appeal as mere schadenfreude, or as the kind of perverse pleasure we get from watching figurative train wrecks. Rather, our apocalyptic fantasies capture something we long for: the chance to do it all over, to simplify, or to get out from under something like debt or loneliness or dissatisfaction. It is decluttering on a grand scale. It allows the possibility of living life on our own terms. We can be heroic and put all of our skills to work. We can set our own agenda in ways that we currently cannot. We realize it would be tough, but we would be focused. Life would be hard but simple and satisfying. We tell ourselves that, at least. Many apocalyptic narratives reflect these fantasies, in which we can be the kind of hero we cannot be in our current lives.