Why we need to praise kids’ teachability — not just their ability

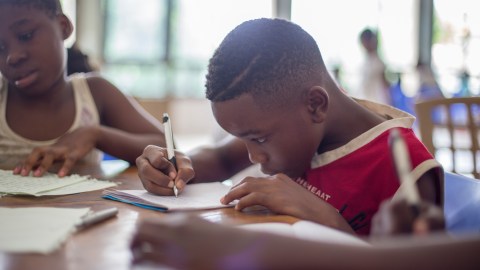

Photo by Santi Vedrí on Unsplash

- Our education system often caters to identifying and supporting gifted children.

- However, an excessive focus on giftedness may not be the best approach for educators.

- Instead, we may want to emphasize the role of growth and teachability in future success.

In Western societies, we like to put people on pedestals. In a culture that celebrates independence, merit, and personal responsibility, our favorite figures are those that seem to simply be cut from better stuff than the rest of us. Characters like Albert Einstein, Beethoven, Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and others are apparently superhuman, and we tend to revere them as such.

Soon after Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon developed the precursor to the IQ test, educators began applying these tests to school children, eager to identify which members of the classroom belonged to the cream of the crop and which were merely average.

This began a veritable obsession with the finding and encouraging of gifted children in our schools. The worst thing in the world, it seemed, would be to let a gifted child’s intellectual capacity go to waste for not giving them the opportunity to demonstrate their giftedness. Probably, there was also the innate attraction one has for intellectual titans; imagine the bragging rights if you got to teach Bill Gates in elementary school.

But this attitude has gradually been shifting, and with it have come new ideas about where to focus our research and education efforts. Rather than seeking out the handful of students with innate talent and encouraging them as much as possible to excel to the absolute heights of our society, maybe we should be focusing instead on the students that show the most teachability.

Photo credit: Stanislav Kondratiev on Unsplash

Growing beyond the cream of the crop

Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck was one of the firsts to study this divide. At its core are two basic mindsets: fixed versus growth mindsets.

Individuals with a fixed mindset view talents and gifts as innate. It argues that you can’t become more intelligent than you are because that’s just how you were born. Maybe there’s a bit of wiggle room, but for the most part, you’re just as capable as you’re ever going to be. With this perspective, the talented amongst us seem more special than the rest of us average folks.

The growth mindset is just the opposite. Sure, there is a measure of innate talent in all of us, but the most important factor in cultivating that talent is hard work. From this perspective, a hardworking kid without talent will outperform a gifted kid that coasts by on their gifts alone.

Dweck argued that individuals with fixed mindsets prioritize appearing as smart as possible, a reasonable strategy if you think that your talent (and therefore your worth) are fixed. They avoid challenges because challenges are opportunities to fail and look stupid, thereby diminishing their worth.

Individuals with a growth mindset, however, seek out challenges. These are opportunities to improve their abilities and to learn new lessons. Fortunately, growth mindsets can be taught — our personality and experiences might encourage us to lean toward one more than the other, but this can be deliberately changed. In one intervention, middle-school students were exposed to a growth-mindset program, teaching concepts such as the neuroscience behind the brain’s malleability and strategies for strengthening the brain as though it were a muscle. Then, the researchers measured the students’ performance in mathematics. Control groups tended to do worse over time, but the intervention group didn’t just perform better than the control, they actually performed better and better over time.

Some criticism has been issued toward Dweck and the fixed versus growth mindset theory. Some psychologists have failed to replicate Dweck’s results, criticizing the theory as a result, but she argues that the implementation of programs to encourage growth mindsets has been poor. To prove this, Dweck and her colleague David Yeager recently published a study demonstrating the impact of two 25-minute-long online sessions relating to the promotion of growth mindsets on 12,000 ninth graders.

Even this extremely small intervention appeared to have an effect. On average, grades grew by 0.1 points, and the proportion of students who got a D or an F dropped by 5 percent. Crucially, however, these effects were larger in schools that Dweck and Yeager identified as having a culture centered around growth mindsets. In these schools, grades went up by .15 points and the likelihood of getting a D or an F dropped by 8 percent.

Findings like these show us that, paradoxically, if we want to raise more gifted students, we shouldn’t focus on their giftedness. Talent hardly matters in the face of teachability. Students who are willing to learn and to work harder are more likely to succeed and become gifted; not students who are already gifted to begin with. Einstein, Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and other titans of their fields obviously possess exceptional intelligence, but they are also hard workers and lifelong learners.