26 ultra-rich people own as much as the world’s 3.8 billion poorest

Getty Images and Wikimedia Commons

- A new report by Oxfam argues that wealth inequality is causing poverty and misery around the world.

- In the last year, the world’s billionaires saw their wealth increase by 12%, while the poorest 3.8 billion people on the planet lost 11% of their wealth.

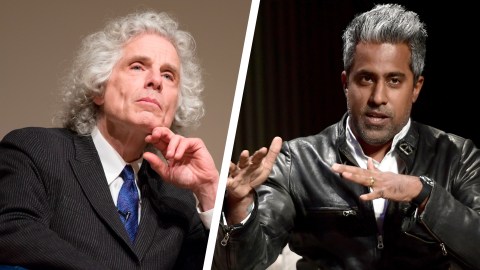

- The report prompted Anand Giridharadas to tweet: “Don’t be Pinkered into everything’s-getting-better complacency.” We explain what Steven Pinker’s got to do with it.

A new report by Oxfam argues that inequality around the word is so out of hand that it is putting progress at risk. The report offers a scathing indictment of policies advanced around the world over the last few decades. The authors propose vast expansions of public services paid for by increasing taxes on the super wealthy to remedy the problems they examine in their report.

Credit: Oxfam

Inequality for all?

The report, titled ‘Public Good or Private Wealth‘, praises the progress that has been made in eradicating extreme poverty around the world over the past few decades. It then warns us that the problems we face today place that progress at risk and even threaten to undo the efforts of countless individuals, governments, and NGOs.

It begins by revealing that the number of billionaires in the world has doubled since the financial crisis of 2008 and that they collectively grow richer by 2.5 billion dollars a day. This is made possible, it explains, by the ever-decreasing tax rates on high incomes and corporations. The choice to cut taxes means there is less money in the coffers to pay for public services and comes at a high cost to those who need them the most.

The figures explaining that cost are shocking. In the last year, the world’s billionaires saw their wealth increase by 12 percent while the poorest 3.8 billion people on the planet lost 11 percent of their wealth. All of the wealth those 3.8 billion people do have adds up to the same amount held by the 26 wealthiest people on the planet.

As a direct result of lack of public services, people die and the poverty trap becomes harder to escape. The report explains that 10,000 people will die today due to lack of proper medical care, 262 million children will not be allowed to go to school for lack of funds, and the poorest women on the planet will do millions of hours of unpaid care work.

Credit: Oxfam

All of this means it should come as no surprise that the rate of poverty reduction is half of what it was in 2013. Even while the number of people living on less than $1.90 a day – the World Bank’s line for extreme poverty – has continued to drop, 3.4 billion people still live on less than $5.50 a day, which is the benchmark for extreme poverty in an upper-middle income country. The authors hasten to add that in Sub-Saharan Africa the extreme poverty rate has started to increase.

While the report focuses on devolving nations, it references conditions in the United States several times. It mentions how social mobility in the United States has been declining for some time and how a black child born in the United States is more likely to die before their first birthday than a child born in Libya.

The report firmly lays the blame for these facts at the feet of declining public services, inequality, and policies that favor the rich, arguing that “Inequality is a political and a policy choice” and that the growth of the top 1% is preventing the reduction of poverty. One section in the report explains the poverty mentioned above:

This is a direct result of inequality, and of prosperity accruing disproportionately to those at the top for decades. The World Inequality Report 2018 showed that between 1980 and 2016 the poorest 50% of humanity only captured 12 cents in every dollar of global income growth. By contrast, the top 1% captured 27 cents of every dollar. The lesson is clear: to beat poverty, we must fight inequality.

The report also explores how these problems tend to harm women more than men. Since women tend to own less wealth than men, policies that benefit the rich are less likely to help them. Women are also expected in many cultures to take care of children, the sick, and the elderly – tasks made much harder if public services like health programs and childcare are cut back.

The Oxfam report tells us that if a corporation did all the unpaid care work the women of the world do and charged people for it, that business would be 43 times larger than Apple. If this work were to be supported by public services, we are told, women around the would be able to spend that time more effectively improving their situation.

How do they propose we fix this problem?

The report does not merely complain without offering a way forward. The authors point to the places where progress is being made on these issues and conclude that increased funding to public services financed by taxes on the super-rich will go a long way in solving them.

For example, a wealth tax placed on the top 1 percent of income earners would provide 418 billion dollars each year, enough to ensure that every child on the planet has access to an education – a necessity if global poverty rates are going to be reduced.

They propose universal health care and education, an end to privatizations of public services, public pensions and child care, and investments in public utilities to help fix inequality. They advise that all of these policies must be implemented in ways that “also work for women and girls” if they are to be successful.

What do Big Thinkers have to say about all this?

Anand Giridharadas, an author who has written extensively on inequality, took to Twitter to comment on the report. He has argued in his books that inequality prevents society from making progress on certain problems because the people with the most wealth will use that wealth to keep the system that made them wealthy in place, even at the cost of inhibiting social reform.

In line with his previous comments on inequality, he argues that these figures are a sign that:

“The tremendous gains that government action, markets, aid, labor unions, philanthropy and other things have made in improving the human condition are now imperiled by the wealth concentration those improvements have left unbothered.”

He also takes aim at those who think this is a glitch in the system or that the problem will solve itself. In one particularly scathing tweet, he warns: “Don’t be Pinkered into everything’s-getting-better complacency.”

Stunning new data:

The world’s 2,200 billionaires grew 12 percent wealthier in 2018. Meanwhile, the bottom half of the world got 11 percent poorer.

Don’t be Pinkered into everything’s-getting-better complacency.

The few are monopolizing progress.https://t.co/89ZZWFpz6S

— Anand Giridharadas (@AnandWrites) January 21, 2019

What’s Steven Pinker got to do with it?

Giridharadas’ tweets mention Steven Pinker, a Canadian psychologist and author, who has yet to comment on the report publicly. Pinker is known for taking a nuanced but controversial attitude toward inequality.

In his book Enlightenment Now, Pinker explains why he doesn’t think inequality is inherently bad. Instead, he argues that we should focus on questions of poverty and unfairness which are tied to the discussion around inequality. In one section he cites philosopher Harry Frankfurt to explain his stance:

“Frankfurt argues that inequality itself is not morally objectionable; what is objectionable is poverty. If a person lives a long, healthy, pleasurable, and stimulating life, then how much money the Joneses earn, how big their house is, and how many cars they drive are morally irrelevant. Frankfurt writes, “From the point of view of morality, it is not important everyone should have the same. What is morally important is that each should have enough.” Indeed, a narrow focus on economic inequality can be destructive if it distracts us into killing Boris’s goat instead of figuring out how Igor can get one.”

How he would feel about a report which argues that massive inequality is itself causing an increase in poverty is an open question since it does move beyond viewing inequality as bad in itself and focuses more on how that inequality causes other problems. In the past, Pinker has critiqued those who say inequality is doing that by pointing to absolute improvements in living conditions over time, but he might not be able to do that for much longer.

Anand Giridharadas’ above-mentioned “everything’s-getting-better complacency” is a reference to Pinker’s view that the world is getting better due to the scientific and humanistic worldviews that gained prominence during the Enlightenment. In his words, “the Enlightenment worked,” and we are living in one of the better parts of human history because of it. He isn’t blind to today’s problems, he is just optimistic that those problems can and will be solved.

He also takes the view that the negative side effects of the systems that created these benefits, effects like the building of the atomic bomb, imperialism, and world wars, are “glitches” rather than the results of endemic problems. He has a history of giving various metrics for how the world is improving over time and is likely to continue to do so as long as we keep our Enlightenment worldview.

The global tendency to cut taxes and public services came at a high cost for the poorest. Now, inequality is so high that it threatens to cause progress in poverty reduction to stall or even reverse. While the question of how lousy inequality is in itself remains open, the fact that it has reached a level where it is causing other problems has been settled. What we do next may prove definitive in the battle against poverty or it may halt the progress of the last few decades.