Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Russian, Ukrainian human rights activists

- The Center for Civil Liberties, Memorial, and Ales Bialiatski jointly received the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize.

- All three recipients were applauded for defending democracy and fighting authoritarian rule in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus.

- Though the Nobel Committee claims the decision was not politically motivated, it sends a strong message amid the war in Ukraine.

The Nobel Peace Prize, the most famous and prestigious of all the awards that bear the name of Swedish chemist and dynamite-inventor Alfred Nobel, honors people “who have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” According to Reuters, this year’s contenders included nature filmmaker David Attenborough, environmental activist Greta Thunberg, Tuvalu’s justice minister Simon Kofe, Pope Francis, and the World Health Organization, among many others.

Of these contenders, three were considered especially likely to win the award: Volodymyr Zelensky, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, and Alexey Navalny. President Zelensky refused to leave Ukraine when Russia invaded in the spring, has united Western powers in their opposition against the Kremlin, and now presides over a counteroffensive that pushes ever deeper into illegally annexed territory.

Tsikhanouskaya, a lesser known figure to the average reader, is a Belarusian teacher-turned-politician who ran against incumbent Alexander Lukashenko in the country’s 2020 election. After she protested the rigged results, Lukashenko turned to his security forces to suppress Tsikhanouskaya and her supporters. In Russia, Navalny tried for years to achieve a democratic victory over Putin before falling victim to suppression himself. After being poisoned, he was arrested and imprisoned for violation of arbitrarily set probation terms.

Although none of these people were ultimately awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the members of the Nobel Committee clearly had their eyes fixed on Eastern Europe. To that end, they decided that the prize would be jointly awarded to the Center for Civil Liberties and Memorial, two human rights groups founded in Ukraine and Russia, respectively, as well as to Ales Bialiatski, a Belarusian activist who, like Tsikhanouskaya, has been a longtime critic of Lukashenko’s state.

The winners, the Committee declared:

“…represent civil society in their home countries. They have for many years promoted the right to criticize power and protect the fundamental rights of citizens. They have made an outstanding effort to document war crimes, human right abuses, and the abuse of power. Together they demonstrate the significance of civil society for peace and democracy.”

Center for Civil Liberties

The Center for Civil Liberties was created in 2007 by Oleksandra Matviichuk, a Ukrainian civil rights lawyer campaigning for democratic reforms. Ever since Ukraine became independent in 1991, the country — like other former Soviet states — has been plagued by civil unrest and political corruption. Because democracy dies in darkness, the Center’s day-to-day operations range from monitoring actions of law enforcement agencies to documenting war crimes in the Donbas and other separatist-backed regions. In 2019, the Center launched a “10 inconvenient questions” initiative that sought to publicly question Ukraine’s presidential candidates, including Zelensky, about their stance on important human rights issues.

The Nobel Committee has applauded the Center for Civil Liberties for its “efforts to identify and document Russian war crimes against the Ukrainian civilian population… In collaboration with international partners, the center is playing a pioneering role with a view to holding the guilty parties accountable for their crimes.”

Memorial

Memorial was formed in Moscow by Nobel Prize-winner Andrei Sakharov during the reign of Mikhail Gorbachev, a period that saw not just economic reforms but also expansions of freedom of speech and assembly. Initially, the organization focused on helping victims of Joseph Stalin: people who had been directly and indirectly persecuted during the Great Terror or imprisoned in the gulags.

Memorial organized the Last Address initiative, which placed commemorative plaques on the former residences of “non-persons” stating their name, date of birth, date of arrest, date of execution, and, if applicable, date of rehabilitation. Memorial also manages online databases where the public can contribute information about political dissenters, as well as access previously classified secret police files.

Aside from studying past war crimes, Memorial serves as a watchdog of present-day human rights abuses. In 2007, it helped produce and distribute a documentary film called The Crying Sun, about a Chechnyan village’s courageous but dangerous and to some extent futile attempt to preserve its own cultural identity in the face of Russian occupation. (Despite its historic struggle for independence, Chechnya was incorporated into Russia in 1993. Its current leader, warlord Ramzan Kadyrov, is a close ally of Putin in the war in Ukraine).

Like many human rights groups, Memorial was targeted by the Kremlin. Its Russian branch officially closed down in April 2022 after Moscow courts determined it had failed to comply with Russia’s “foreign agents” law, which holds that any organization receiving international funding has to mark its publications with a “foreign agent” warning — a trivial, contrived bureaucratic pretense not unlike the one that landed Navalny in jail. Memorial still operates abroad, mainly in Germany.

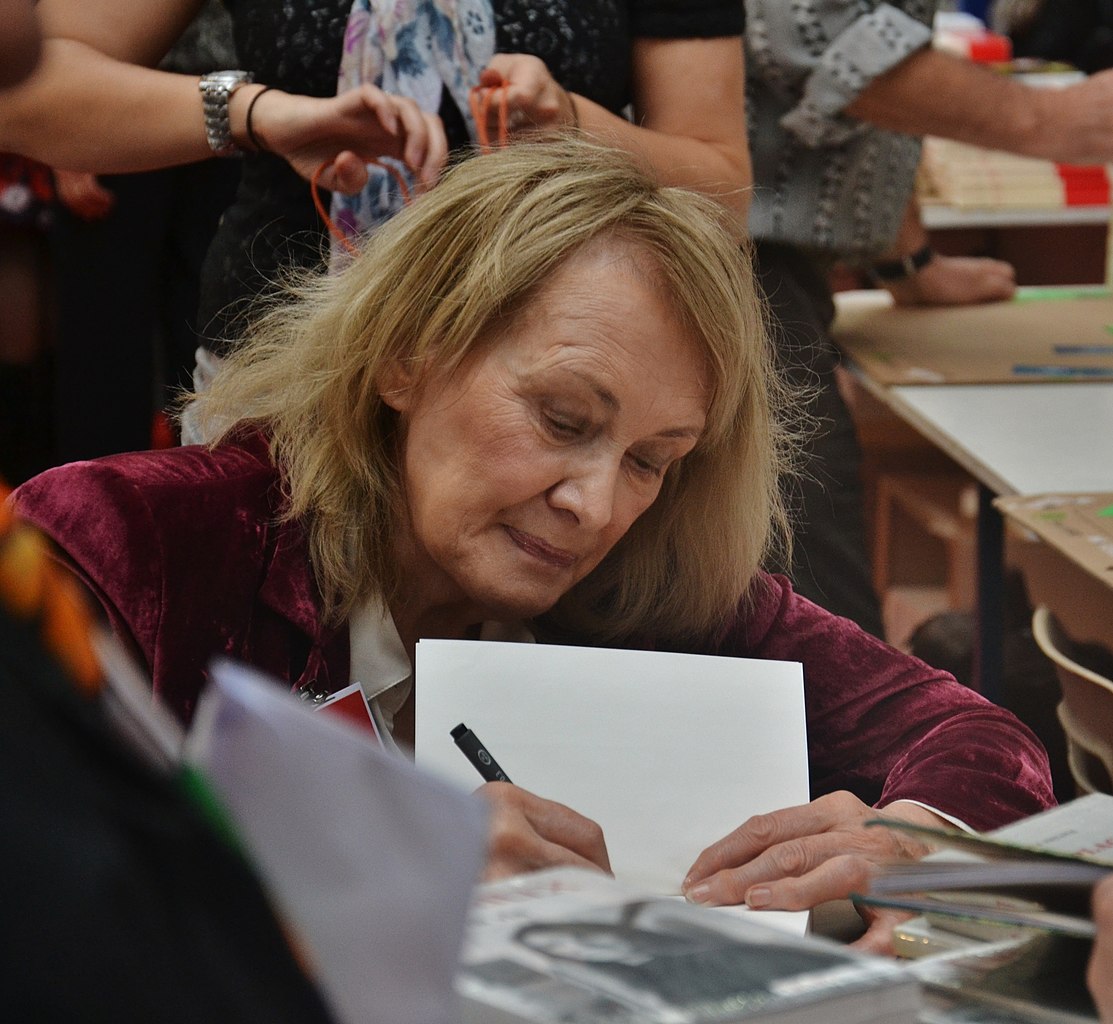

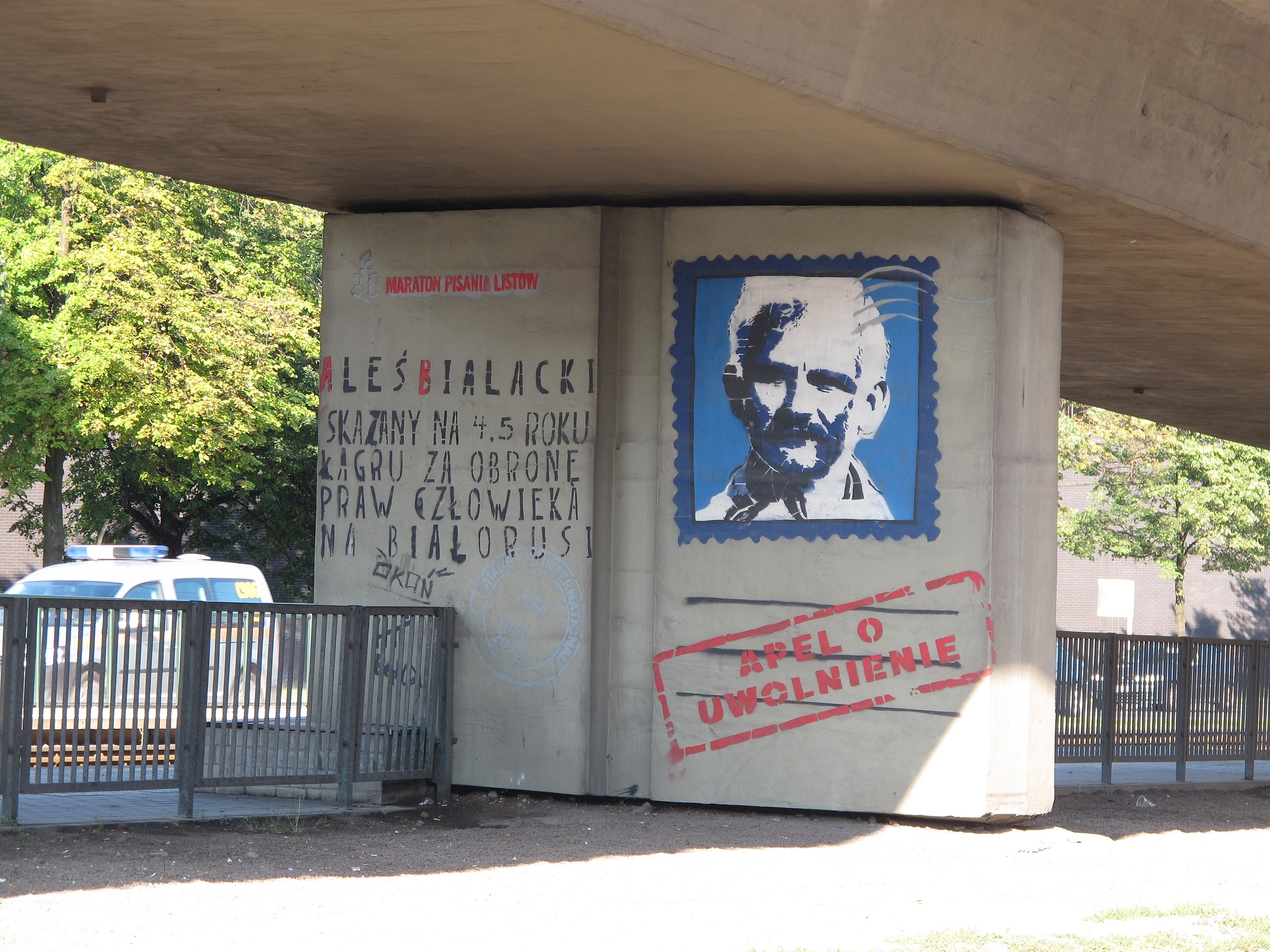

Ales Bialiatski

Ales Bialiatski had been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize five times before finally being awarded one. The Belarusian human rights activist may have won out over Zelensky, Tsikhanouskaya, and Navalny due to the fact that he is a civilian, not a politician.

Bialiatski, a former museum director and scholar of Belarusian literature, has been campaigning for political reforms in Belarus for over 30 years. In the 1980s, perceiving an opportunity presented by perestroika, he supported the republic severing its ties with the Soviet Union to form a sovereign, democratic country. Though Belarus did gain independence, it did not take long before Lukashenko came to power and turned Bialiatski’s would-be democracy into the “last dictatorship” of mainland Europe. In 1996, as demonstrations against Lukashenko’s entrenched regime grew bigger and bolder, Bialiatski helped found the Viasna Human Rights Center, a Minsk-based NGO that, like Memorial, offers assistance to victims of government persecution.

Viasna has achieved many great things over the years. Through persistent lobbying, it convinced the United Nations to place a Special Rapporteur in Belarus in 2012 to search for and gather evidence of human rights abuses. Viasna also has been involved in a global (though primarily European) effort to get Lukashenko to abolish the death penalty. Belarus is the last country in Europe that still executes prisoners, and Bialiatski’s organization provides government agencies with information on the ongoing practice.

For these reasons and others, both Viasna as a whole and Bialiatski in particular are considered enemies of the state. In October 2003, the Belarusian Supreme Court cancelled Viasna’s registration for observing the country’s rigged presidential elections, something it continues to do until this day. Bialiatski himself has been arrested over 25 times. When fines and administrative penalties were unable to get him to withdraw from public life, he was — again, like Navalny — jailed for trumped-up charges of tax evasion. Miklós Haraszti, the then-Special Rapporteur whose office Viasna helped create, called his imprisonment “a symbol of the repression against human rights defenders.” Bialiatski was released in 2014, after serving a total of 1,052 days, but was taken into custody again in 2021, again for alleged tax evasion.

Bialiatski was still in prison when the Committee declared him a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, and it is unknown whether he is aware of his award. Natalia Satsunkevich, a fellow member of Viasna, told NPR that he will probably not hear the news until he is finally allowed to meet with his lawyer. “He is still detained without trial,” the Committee commented. “Despite tremendous personal hardship, Mr Bialiatski has not yielded an inch in his fight for human rights and democracy in Belarus.”

Tsikhanouskaya congratulated Bialiatski in a tweet. “The prize is an important recognition for all Belarusians fighting for freedom & democracy,” she wrote. “All political prisoners must be released without delay.”