The 12 high-school cliques that exist today, and how they differ from past decades

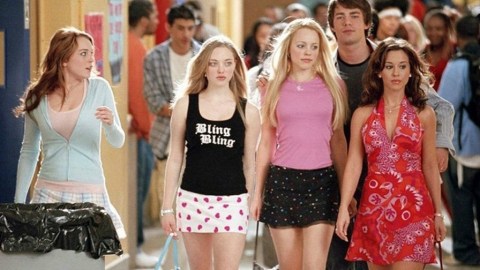

Still from Mark Waters' 2004 film "Mean Girls"

- Researchers conducted focus groups with students who recently graduated from high school to ask them about their experience with peer groups.

- Altogether, the participants identified 12 distinct “peer crowds” and ranked them in a social hierarchy.

- The results show that, compared to past decades, some groups have risen or fallen in the hierarchy, and a couple new groups have emerged.

How do modern high-school peer groups compare to the familiar cliques of past decades — jocks, stoners, brains? A new study explores that question and highlights a few new groups that have formed in the high-school social hierarchy, offering insights into adolescents’ changing attitudes that stem, in part, from the increased pressure to obtain a college degree.

The findings, published in the Journal of Adolescent Research in December of 2018, come from a series of focus groups that researchers conducted with recently graduated and ethnically diverse students who were born between 1990 and 1997, and enrolled in one of two U.S. universities.

To get an idea of students’ recent high-school experiences with peer groups, the researchers, working at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the University of Texas at Austin, asked their focus groups to write down the various cliques that existed at their schools, and then to try to agree upon common groups that existed at all of the schools. After, the researchers asked the students questions, like:

- Which groups was most popular?

- How well did they do in school?

- What kinds of clothes do they wear?

- What race, gender, income are they?

- How good looking are they?

- Where do they hang out after school?

- What do they do on weekends?

The students identified 12 general “crowds” in modern high schools: populars, jocks, floaters, good-ats, fine arts, brains, normals, druggies-stoners, emo/goths, anime-manga kids, and loners. The researchers also classified these crowds into two groups: conventional and counterculture, with “conventional crowds embracing the values typically rewarded by the U.S. educational system and counterculture crowds opposing and/or providing alternatives to them.”

Differences of modern cliques & the pressures of getting into college

In many ways, modern cliques seem to reflect the high-school peer groups of past generations. For example, the top of the modern social hierarchy is occupied by familiar and conventional crowds such as jocks, talented students and popular kids — not exactly a surprise.

However, the “brains” crowd, located in the middle of the social hierarchy, seemed to differ from past decades. Characterized by getting good grades, students often remarked how this crowd seemed overly consumed by academics and the desire to get into a top-tier college, a preoccupation not observed by past researchers.

“Participants identified academic anxiety in more specific terms, even suggesting that students in the ‘brain’ peer crowd ‘were less mentally healthy’ due to a fear of upsetting their parents,” Rachel Gordon, lead study author and professor of sociology at UIC, told UIC Today.

Competition to get into good colleges seems to have shaken up the high-school hierarchy in other ways, too.

The fine arts crowd, for example, has been around for decades, but now it seems to be growing in status and prevalence, a rise the researchers attributed to the importance of participating in extracurricular activities for college admissions. Meanwhile, the researchers identified a new crowd: the so-called “good-ats,” who, as the name implies, are well-rounded and exceed at academics, sports and extracurricular activities.

Of course, past generations had similar kinds of students — researchers called them “athlete-scholars” or “beautiful brains.” But the good-ats differ from these groups, according to the researchers, because of their drive to achieve in several different fields at once. Again, the researchers suggested this drive likely reflects “the need for college-bound students to appear ‘well-rounded’ in college applications.”

Another new group identified in the study is the anime/manga crowd, which participants characterized as “being unattractive, outlandish, and socially awkward.”

“They probably wear clothing that represents video games and anime,” said one participant. “Yeah, a lot of fandom stuff and cosplays [dressing as anime characters],” said another student. “Colored hair. . . . You have to have weird colored hair and headphones.”

This group “resembled geeks, dorks, nerds, and dweebs in past U.S.-based studies,” and their social life exists mainly online, the researchers noted.

Photo credit: Jerry Kiesewetter via Unsplash

Low-status cliques reflect changing times

The study suggests lower-status crowds are more heavily influenced by current events, popular culture and social media. Gordon provided several examples of this apparent connection to UIC Today, among them:

- The emergence of the “anime/magna” peer crowd, which she said is a modern-day incarnation of a classic “computer geek” crowd that is likely promoted by a sharing of cultures on the internet.

- The “emo/goth” crowd, who share with past decades a focus on countercultural behaviors, but focus on today’s music and aesthetics.

- The expressed fear of “loners” as potential perpetrators of violence, something that Gordon described as “new and unique to adolescents today, potentially reflecting the prevalence of school shootings over the last 20 years.”

White students perceive crowds differently

The study found that crowds at the top of the social hierarchy were often characterized as white, and that white students were likely to describe racial-ethnic crowds as monoliths, and they did so in “racially-coded language.” However, students of color tended to observe much more variance within racial-ethnic groups, as one black student described:

“… there’s so much variation. You have good-looking black people. You have not good-looking black people. You have smart black people and not so smart, you have healthy and then not healthy.”

Students of color generally said that, unlike white students, they were inextricably tied to the members of their racial-ethnic group. Because of this, a 12th group was included in the researchers’ new hierarchal pyramid. The researchers wrote:

“When students of color identified racial-ethnic crowds, they saw them as home bases to which they were automatically members, in a positive way. One focus group participant described how a student of color could not be ‘completely in another group because they were in [a racial-ethnic] community by default [because] that’s just who they are.'”

Still from the 1993 Richard Linklater film “Dazed and Confused.” Image source: Gramercy

Why do cliques form?

Most people frame cliques in a negative light, and it’s no wonder: They often lead to social exclusion and isolation, and also, in case you’ve never seen a Hollywood high-school movie, some pretty obnoxious behavior. Still, cliques are likely just a result of human nature — the desire to sort ourselves into groups for reasons of familiarity and certainty, control and dominance, and security and support, as Mark Prigg wrote.

Or, more simply, we form cliques because we want to surround ourselves with people like us, a preference that’s as deep-rooted as “our anxieties about people who are different and our ambition for status within our community,” as Derek Thompson wrote for The Atlantic.

In any case, studying cliques could help scientists and educators find ways to make schools safer and better places to learn.

“Adolescent peer crowds play an important role in determining short-term and long-term life trajectories on social, educational and psychological fronts,” Gordon told UIC Today. “Understanding how adolescents navigate their environments and perceive themselves and others can help us advance research in many areas, from how we can successfully promote healthy behaviors, such as anti-smoking or safe sex messages, to how we develop effective curriculums or even mediate the effects of school shootings.”