What value does the word “millennial” actually have?

Americans have heard the term ad nauseam by now. In politics, public relations or marketing, it’s a buzzword.

But millennial doesn’t hold nearly as much meaning as Americans pretend it does. Here’s why.

It doesn’t mean what we often say it means

A recent news story in Fox News was an example of a common problem – though any examination of news coverage would likely show that such a story is not unique.

The segment, which aired Sept. 12, featured a discussion about the teenage vaping crisis. A health expert asked, “Why is the attraction for the young generation, why the attraction for the millennial population that is using these products?”

Similarly, my university students frequently say, “Well, you know us millennials like or do ‘x.'” I’ll ask for clarification on who they’re talking about. They’ll say, “I don’t know, 18- to 24-year-olds.”

The problem? The use of the term in such a context is wrong. The term millennials has become synonymous with “young people,” “college students” or the like.

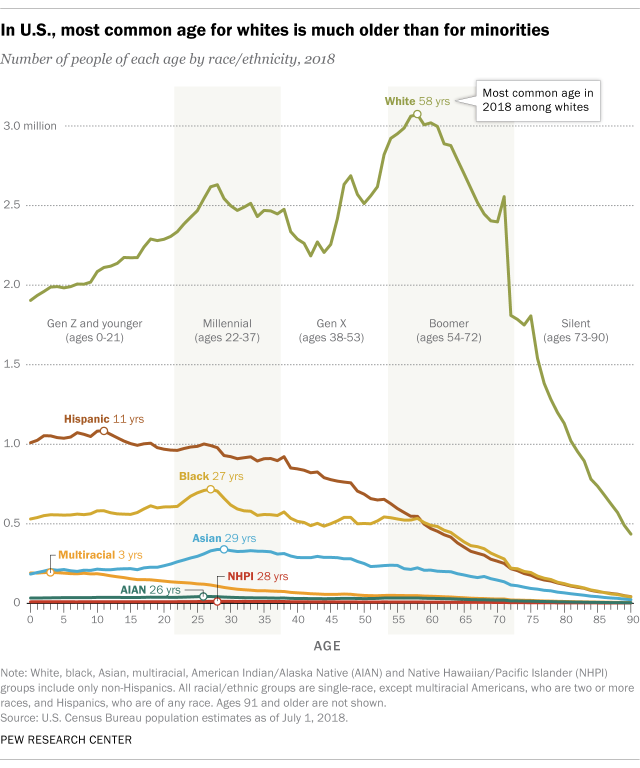

But, while the term has arguably been used the same way for years, the generation is of course aging. While definitions may vary, according to Pew, one of the nation’s leading research organizations, the term applies to those born between 1981 and 1996. As a new generation label is applied about every 15 to 20 years, millennials are now between about 23 and 38.

It’s important to use the right term for the right group. A reference to teens or a typical college student is now a reference to Generation Z, not millennials.

A big, diverse group

Okay, fine. If you get the definition correct and use it properly, then you’re good, right? Millennials are still this collective of young working adults, you say.

No. The term is often meaningless because of the group’s size and diversity. As of this year, millennials have become the largest population group in the country, over 70 million. That’s roughly equivalent to the number of Americans living in the Pacific and Mountain West time zones combined.

Large numbers of people – be it “millennials” or “Americans” – are put into categorical buckets to simplify and make sense of a large amount of information. But that may lead to troublesome characterizations in light of the diversity within such a big group.

For example, the generation is far more racially diverse than previous American generations, as it’s just over half white.

You may have heard some of the stereotypes about millennials. They’re broke college graduates loaded with school loans living with their parents after school. And they’re all single and not having kids.

Perhaps my favorite story that summarized these stereotypes was titled “Millionaire to millennials: Lay off the avocado toast if you want a house.”

Myth-busting

Even a surface-level review of the data busts many of these broad myths.

While millennials are more educated than any previous generation, the majority – about 60% – don’t have a bachelor’s degree.

In the 2020 election, campaigns and news coverage focus on student loan debt among more educated voters, but data actually show that credit cards are the more common type of millennial debt.

Pew has shown that millennials with bachelor’s degrees are actually doing quite well financially – to the tune of over US$100,000 household incomes. This number is just below Gen X and above late boomers with a similar education.

Meanwhile, households led by millennials with a high school education are making less than $50,000. So income inequality based on education differences continues to be a major problem, just as it was with previous generations.

While it is true that millennials are much more likely than other generations to live with their parents, 90% of those with a college degree do not.

The data are similar on the dating and family front. While there is again truth in the broader trend – fewer millennials are married or have kids than the previous generation – about half of millennials are already married or have children.

And, let’s think practically about the age range. How different is one’s life between 23, or the start of the generation, and 38, the end of it? Be it home ownership, family life or job situation, broad discussions are often talking about people in entirely different situations.

Trust me – as an older millennial who has spent most of my university career teaching younger millennials, this becomes clear rather quickly.

The takeaway

So, if use of such broad terms can be misleading or inaccurate, why use them at all?

Use of a broad term in a proper context does allow one to make sense of a large group of people. There can still be meaningful trends that are accurate, such as the fact that nearly 60% of millennials lean toward the Democratic Party.

But, even then, that means about 30 million millennials are not in that category. In a world where tens of thousands of people can decide who is president, any broad summaries miss important points.

I think that the further away industries – like public relations, advertising or political campaigns – can get from lumping people into generalized demographic buckets, the better. Otherwise, they’ll continue to miss useful insights into the nation’s largest group of people.

Joseph Cabosky, Assistant Professor of Public Relations, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.