What do we lose when we can’t get lost?

Photo by Helene Pambrun/Paris Match via Getty Images

- Science writer Maura O'Connor spent four years traveling the world to better understand how humans navigate their terrain.

- She writes "getting lost is a uniquely human problem," noting that other species don't have issues navigating.

- While the book is not anti-technology, O'Connor questions our reliance on GPS and self-driving cars.

In a recent episode of The Portal, filmmaker Werner Herzog says “the world reveals itself to those who travel on foot.” Author Rebecca Solnit dedicated an entire book to walking. In Wanderlust: A History of Walking, she writes that we generally live in a “series of interiors … disconnected from each other.” Walking connects us, to one another and the world itself. “One lives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it.”

Add science writer Maura O’Connor to the list of thinkers championing walking. Her new book, Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World, isn’t about the art of placing one foot in front of another, but about how humans navigate their terrain — and what is lost when we offload our hard-earned navigation skills to GPS.

Wayfinding is not a romanticized screed against technology, yet it does point to important consequences that a lack of landmarking has had on our brains. Toward the end of the book, she speculates on a topic I’ve written about often: the potential that technology and automation will increase cases of dementia. What is being sacrificed in our quest for convenience?

O’Connor is a brilliant writer, a refreshing voice in a deluge of misspelled tweets and Snapchat. (During The Portal, when asked what books have inspired him, Herzog replied that no single book would suffice as an answer; reading is what matters.) The book documents her travels dogsledding in the Canadian arctic and wandering through Australian deserts. Even if you had no interest in the subject matter, Wayfinding is simply a joy to read.

But we should all be invested in our future. I recently spoke with O’Connor, who was in her office in Gowanus, an area I spent years walking around aimlessly; every Friday I meandered from Tribeca to Park Slope to mark the end of my work week. New York’s grid-like structure and giant landmarks make it difficult to get lost in, yet I’d always walk along different blocks and cross various bridges over the canal to better understand my neighborhood. Getting lost forces you to think critically and problem-solve; there is simply no downloadable replacement for those essential skills.

We discuss GPS and driverless cars in more detail during our talk, which I’ll save for a future article on the topic. The first half of our talk generally centered on her fascinating experiences while wayfinding.

A dog sled team in Nunavut after a race.

Photo by Wolfgang Kaehler/LightRocket via Getty Images

Derek: What was the inspiration for this book?

Maura: I had not thought much about navigation before starting this book. A lot of writers tend to overestimate the importance of their subject matter. But I can genuinely say that navigation is a strange phenomena in the sense that it is something that every single one of us is engaged in every single day of our lives. But it is not something that many of us give much thought to or step back to think about.

The moment that my attention was drawn to navigation in my own life was after having used a smartphone with a GPS device in it for almost eight years. I was using it in a very rural part of New Mexico and it basically led me astray. I was trying to find a hot spring; I put the location into my phone and the GPS directed me to drive to the banks of the Rio Grande.

I was like, “Wow, why do I have such unquestioned faith in my GPS to tell me where to go?” I had that experience and then started thinking more broadly about how it is that gadgets infiltrate themselves into our lives in ways that we don’t necessarily question. In this case, what does it mean to outsource a cognitive skill to a gadget and what are the implications and effects of that? The book really grew out of that question.

Derek: You write that “getting lost is a uniquely human problem.”

Maura: If you consider how many species of animals depend on precise navigation to survive, you see how this is a phenomenon that is really critical to evolution. If there were species that were prone to becoming lost, they wouldn’t survive. Humans, on the other hand, do seem to have this ability, which is confounding. It seems to me that the reason for that is we really don’t have the same kind of biological hardware that a lot of other species have that can tell us almost instinctively or intuitively where we are at all times.

There are countless mysteries about how different species do what they do, but compared to humans, there’s no real doubt that we are pretty miserable navigators compared to even a butterfly or a lowly aphid, let alone leatherback turtles that travel 6,000 miles over an open ocean to get from one habitat to another.

We’ve created cultural traditions and ways of transmitting and teaching skills from one generation to the next. We use culture to make up for the deficit of biological mechanisms that other species seem to have.

Derek: I really appreciated your deep dive into maps as metaphors for the cultures that create them. It made me think of the very common world map that we grew up with in America. Our country seems as large as Africa even though we can basically fit inside of the Congo. What does the type of map that someone creates tell them about the culture?

Maura: I realized pretty quickly during my research and talking to different anthropologists and going to some of the places that you mentioned [the Arctic and Australia] was that maps, to my surprise, are not universal, whether a physical paper map or a cognitive map. There is extensive debate in anthropology and neuroscience and psychology over whether or not maps are culturally universal. What I found was, based on my own readings, they’re not. That raises this really interesting question: How could we possibly find our way without a map?

That instrument is so central to anybody who’s grown up in an urban environment or in Western culture that it’s almost inconceivable to think of other strategies for navigation. But actually there’s this astonishing range of human navigation systems that use observation, memory perception, environmental cues, and different types of language to describe space.

Some may not use a God-like bird’s eye view of space, but actually use a different type of strategy. Sometimes it’s called route-finding: “Here is the tree and, after the tree, there will be a mountain, and after the mountain there will be a lake.” You’re really navigating from the perspective of the individual on the ground moving through space. That’s one of the most satisfying revelations that I discovered through writing the book because it just deepens the mystery and diversity around human culture.

GPS and the Human Journey – M.R. O’Connor | The Open Mind

Derek: Our brains have this very unique paradox in that we are attracted to novelty and new situations, but at the same time we will default to the easiest possible way if it’s going to conserve energy. We want speed and efficiency. Did anyone in the course of your book discuss what is lost when they transition to more convenient tools for navigation?

Maura: Yes. I went to Nunavut, which is a sovereign part of the Canadian Arctic. You kind of expect to just show up and say, “Which hunters can take me out on their dog sleds?” I discovered this was like showing up in New York City in the 21st century and being like, “Hey, who can take me on a ride on a horse and carriage?” It was quickly explained to me that hunters are not very romantic. If there is a practical advantage of using a rifle over a harpoon, then that is a choice they will make because the necessities of hunting in the Arctic are so challenging and extreme.

I found that a lot of hunters, even those using traditional navigation skills, use snowmobiles. Some of the hunters told me is that the biggest difference between being on a dog sled and a snowmobile when you’re trying to navigate is speed and how much you can actually attend to when you’re traveling 60 miles an hour versus 15 miles an hour. Traditional Inuit navigation relies on this attention to detail because the landmarks in the Arctic are so different from what anyone from the south would consider a landmark.

What I also saw was a tremendous effort on the part of community leaders and hunters in those communities to preserve these skills and pass them down to the next generation. It’s not just about hunting; navigation is extremely crucial to Inuit identity and culture. It ties into language, it ties into oral storytelling, it ties into their relationship and the stewardship of the land itself.

Derek: You also write that narration may have begun in hunting society. You were talking about how a tracker in Australia imagines being in the mind and body of the author of the trackway and then creates a narrative.

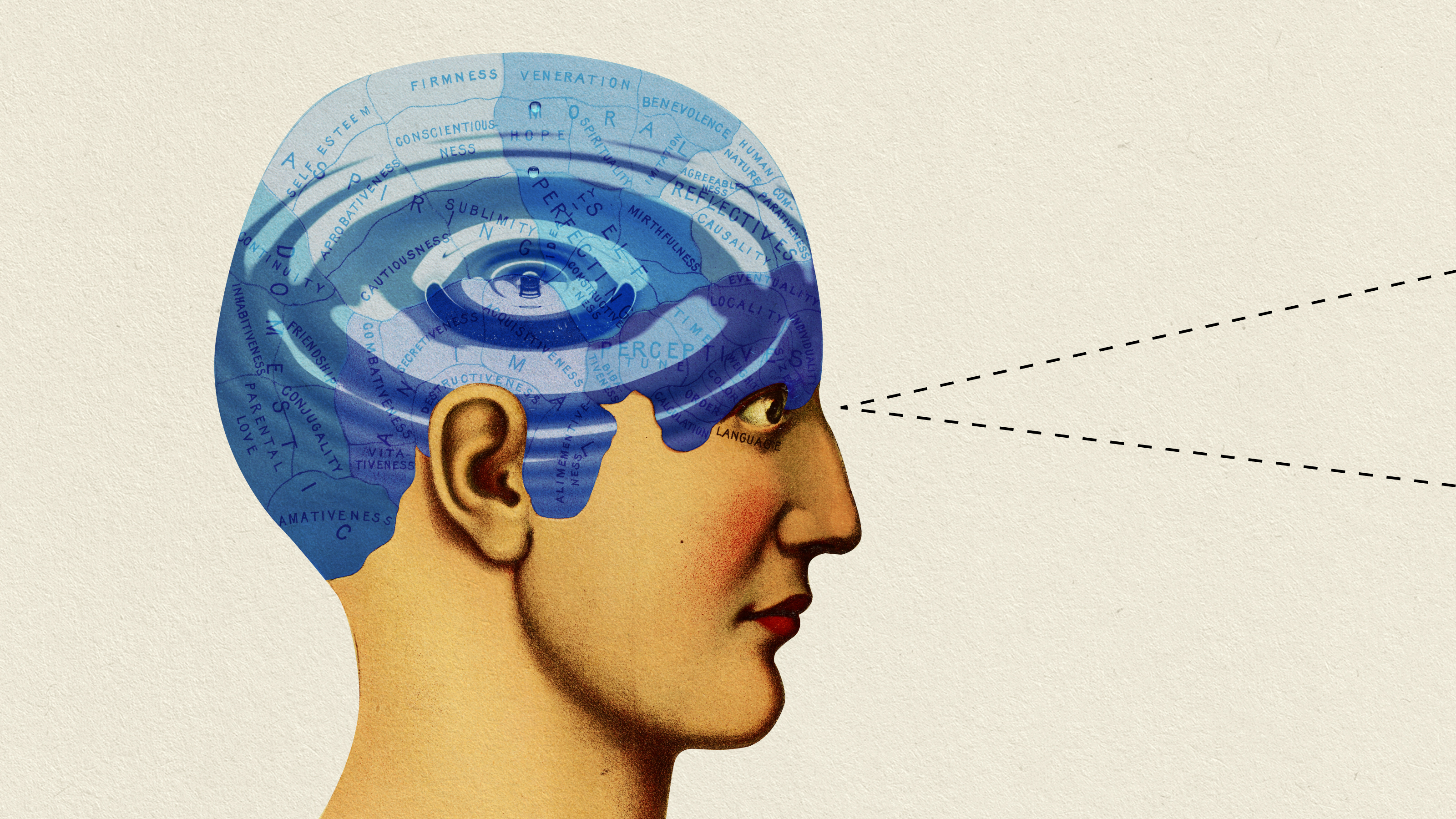

Maura: I think this link between navigation and storytelling was also something that was unexpected to me. We are the only species that seems to have so thoroughly used memory to assist us in the task of navigation. That’s what’s called episodic memory, which is our ability to recall events that happened in the past based in the hippocampus, which is the same exact area of the brain where navigation and spatial orientation takes place. Interestingly, the hippocampus is also this part in the brain that allows us to imagine ourselves in the future.

It seems that the hippocampus is intrinsic to this ability to develop narratives and stories about where we were in the past, how we came to be, where we are now, and where we are going in the future. It is really interesting that navigation may have helped us to develop this narrative capacity.

Different cultures have used this narrative capacity as a sort of mnemonic device; they’ve used stories as devices to encapsulate topographic information. The best example of that, as you mentioned, is aboriginal Australians, who have tens and tens of thousands of years of history of using songlines. Those are essentially stories about how aboriginal Australians ancestors created the topography of the landscape through their travels in a time called the dream time. The journeys of those ancestors are recorded in songs and stories that people learn and memorize.

Songlines are not just repositories for incredible environmental ecological knowledge, aboriginal law, and history, but that they’re also navigation aids. These journeys are actually routes that people could literally follow through the landscape to get from one place to the other.

Kata Tjuta at Sunrise, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, Australia.

Photo by: Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Derek: I initially reached out to you after your book was excerpted in The Washington Post. The excerpt focused on how GPS is damaging our brains. What do you think is being lost when we’re using devices like GPS?

Maura: The psychologist James Gibson came to the conclusion that this whole idea of Cartesian dualism, that we’re not actually interacting directly with the world around us because the brain is this mechanistic process that’s creating images of the world for us and we’re never in direct contact, wasn’t really satisfying. He created all these tests to test the idea of a theory he called ecological psychology.

The idea is that the brain is just part of a complete visual system and that natural vision involves eyes in our heads connected to a body which is walking on the ground. Unencumbered exploration is really about us looking at things from all perspectives moving forward. I don’t think it was his main objective, but he created this alternative theory of navigation, which is that navigation really depends on us directing our attention and directly perceiving the environment.

I won’t argue that GPS is not an incredibly powerful tool that has many positive benefits for us to use. But I think there’s no debate that it really changes the way we direct our attention. It seduces our attention downward, whereas what Gibson was talking about is this very powerful directing of attention, giving attention to the environment and paying attention to what we see as we move through the environment. Those two things are just really different practices and perhaps we can argue the benefits of one over the other in different contexts. But I do think that using a gadget really changes that process a great deal.

Derek: You cite a 2008 study about people walking while using GPS (as compared to experience or paper maps) walk more slowly and make greater direction errors; it was also tougher for them to find their way. I personally believe that we’re going to see a massive uptick in degenerative diseases.

Maura: This is a pretty nascent field of study, but there are studies coming out of different areas of cognitive disease, aging memory, and navigation, as well pointing at an interesting relationships between spatial orientation strategies, the hippocampus, and cognitive disease. They’re not showing a direct relationship between using a device to find your way and turn-by-turn directions. But what they’re showing is that our attention really changes when we use those devices.

We’re finding out about how the hippocampus changes as we’re using different technologies. There’s lots of information about diseases like Alzheimer’s, dementia, PTSD, and even depression that shows that atrophy in the hippocampus is in many cases universal among those afflictions, particularly Alzheimer’s disease.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.