Today is the 50th anniversary of the Kent State shooting. Here’s what happened.

National Archive

- The killings marked the height of escalating tensions between protestors and police in Kent, Ohio, during the spring of 1970.

- Despite how the culture views the tragedy today, the majority of Americans sided with the National Guard shortly after the incident.

- To this day, nobody knows exactly why the guardsmen decided to open fire on the crowd of students.

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the Kent State massacre, in which the National Guard killed four students during a protest against the Vietnam War.

The killings on May 4, 1970 marked “the day the war came home.” The already-polarized nation was never the same. After the story broke, with John Filo’s famous Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph on the front page of newspapers nationwide, millions of students began organizing school strikes and protesting on a larger scale.

The massacre went on to shape public opinion of the Vietnam War, and some historians suggest it played a role in the downfall of former President Richard Nixon, and helped influence Congress to pass the War Powers Act in 1973, which limited the president’s powers to wage war.

In Kent, Ohio, the killings marked the bloody climax of an especially tense week between protestors and police. It started on April 30, when Nixon announced the U.S. would invade Cambodia — a move that came 10 days after the president had announced the withdrawal of 150,000 troops from Vietnam.

On May 1, about 500 students protested on the campus commons of Kent State University, where they buried a copy of the U.S. Constitution and posted a sign on a tree that read: “Why is the ROTC building still standing?” On May 2, the university’s ROTC building was set on fire. According to the report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest:

“Information developed by an FBI investigation of the ROTC building fire indicates that, of those who participated actively, a significant portion weren’t Kent State students.”

The National Guard arrived in Kent shortly after the building was set ablaze. On May 3, Ohio’s Republican Governor Jim Rhodes held a press conference where he pounded on a desk and called the protestors “the worst type of people that we harbor in America.”

May 4 fell on a Monday. Student protest leaders had called for a rally to be held on the campus commons around noon. Earlier that morning, the university had distributed thousands of leaflets declaring all rallies to be illegal, as the National Guard now controlled campus.

Around noon, hundreds of students had gathered on the commons, which was also occupied by about 100 guardsmen with gas-masks and M-1 military rifles. In total, there were approximately 3,000 people at the scene — 500 demonstrators, 1,000 “cheerleaders” who supported the active protestors, and about 1,500 spectators, according to Kent State University.

Here’s how Jerry M. Lewis and Thomas R. Hensley, Kent State professors of sociology and political science, respectively, once described what happened next:

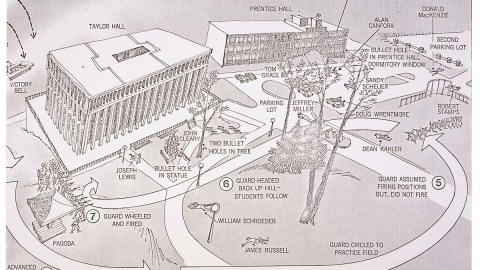

“Shortly before noon, General Canterbury made the decision to order the demonstrators to disperse. A Kent State police officer standing by the Guard made an announcement using a bullhorn. When this had no effect, the officer was placed in a jeep along with several Guardsmen and driven across the Commons to tell the protestors that the rally was banned and that they must disperse. This was met with angry shouting and rocks, and the jeep retreated. Canterbury then ordered his men to load and lock their weapons, tear gas canisters were fired into the crowd around the Victory Bell, and the Guard began to march across the Commons to disperse the rally. The protestors moved up a steep hill, known as Blanket Hill, and then down the other side of the hill onto the Prentice Hall parking lot as well as an adjoining practice football field. Most of the Guardsmen followed the students directly and soon found themselves somewhat trapped on the practice football field because it was surrounded by a fence. Yelling and rock throwing reached a peak as the Guard remained on the field for about 10 minutes. Several Guardsmen could be seen huddling together, and some Guardsmen knelt and pointed their guns, but no weapons were shot at this time. The Guard then began retracing their steps from the practice football field back up Blanket Hill. As they arrived at the top of the hill, 28 of the more than 70 Guardsmen turned suddenly and fired their rifles and pistols. Many guardsmen fired into the air or the ground. However, a small portion fired directly into the crowd. Altogether between 61 and 67 shots were fired in a 13-second period.”

Ultimately, four students were killed, and nine were injured. The dead were: Miss Allison B. Krause, 19, Pittsburgh, Pa.; Miss Sandy Lee Scheuer, 20, Youngstown, Ohio; Jeffrey G. Miller, 20, Plainview, N.Y., and William K. Schroeder, 19, Lorain, Ohio. Eight Ohio National Guardsmen later faced criminal charges, but all were acquitted.

“There is no evidence from which the jury could conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendants acted with premeditation, prior consultation with each other, or any actively formulated intention io punis or otherwise deprive any students of their constitutional rights,” a federal judge wrote in 1974.

Some details of that spring afternoon remain murky. But what’s clear is that America was violently polarized in 1970. The nation was five years into the Vietnam War, which had already killed thousands of young draftees and helped spawn the counterculture movement and its accompanying protests — some peaceful, some violent.

A culture war was escalating. Broadly speaking, it was between young Americans who felt disillusioned by the violence and status quo, and a more conservative swath of the country who felt the war was necessary, or even patriotic. After all, young Americans were dying abroad on behalf of their country: Was it all for nothing?

It’s worth considering this culture war when looking back at Kent State. After all, not all Americans viewed the incident as a misuse of state power, as it’s widely portrayed today. In fact, shortly after the killings, the majority of Americans (58 percent) supported the guardsmen. And that anti-anti-war sentiment sometimes manifested violently.

For example, during the “Hard Hat Riot” of May 7, construction workers in New York City beat student protestors who were trying to shut down Wall Street a day after marching through Manhattan for the funeral of one of the students slain at Kent State. Some of the “hard hats” even chased students back to Pace University and invaded buildings. The riot marked a symbolic turning point in which the Nixon administration was able to win over some working-class Democrats who had grown fed up with the anti-war movement. “These, quite candidly, are our people now,” top aide Patrick Buchanan told Nixon.

May 4, 1970: The end of the ’60s

May 4 was the day the ’60s died, say some historians. But the Kent State massacre wasn’t the only instance around the turn of the decade where police killed unarmed protestors. In 1968, during an anti-segregation protest on the campus of South Carolina State University, the South Carolina Highway Patrol killed three black student protestors, and shot more than 20 protestors as they tried to run away. In 1969, police shot and killed a 25-year-old protestor during a demonstration near UC Berkeley. And on May 17, 10 days after Kent State, police in riot gear killed two students during a protest at Jackson State, a historically black college.

To this day, nobody knows exactly why the guardsmen decide to fire on the unarmed students at Kent State.

“No one knew the national guard had real bullets. We were completely shocked. It just never occurred to anyone that they would actually have bullets to shoot people. It may sound naive but we talked about that for years afterwards,” said Lou Capecci, a former Kent State student who attended the May 4 protest.