Illegal sand mining in India is fatefully hurting gharial crocodiles, Ganges River dolphins

Photo credit: Andrew Caballero-Reynolds / AFP / Getty Images

- India’s construction industry is booming, which means that demand for concrete is very high.

- Sand is a crucial ingredient in concrete, but mining it can cause significant environmental damage.

- The Indian government has, therefore, regulated the mining of sand — but doing so is an easy way for many Indians to earn some extra money. As a result, illegal sand mining has become a commonplace activity, leading to corruption and sometimes violence.

All across India, high-rise developers and construction companies are building hotels, businesses, and homes, turning the country’s horizon to a skyline. Over the next 20 years, $650 billion is expected to be invested in urban infrastructure alone. The construction industry employs 35 million people, the second largest sector in India after agriculture. All those buildings, after all, need people to build them.

However, the vast majority of those buildings are being constructed with concrete — and that’s a problem. One of the main constituents of concrete has become so valuable in India that the excess mining of this material is destroying local ecosystems, damaging crops, and drying out rivers.

Mining practices around this material is being carefully regulated, but it’s worth so much that loosely-formed criminal organizations have formed to skirt the government’s rules and extract this substance from the earth, regularly relying on violence to ensure its steady supply.

But this isn’t any particularly rare substance: it’s sand.

Kashmiri boatmen collect sand along the banks of the Jhelum River.

Photo credit: SAJJAD HUSSAIN / AFP / Getty Images

Surprisingly dangerous

At first blush, sand mining might not seem like it could do all that much damage. However, sand plays an important role in any environment with a river, lake, or coastline. As sand is removed from the environment, the water table drops lower and lower. This makes it difficult for people to get access to clean drinking water and it destroys the environments that various animals — and plants — need to survive.

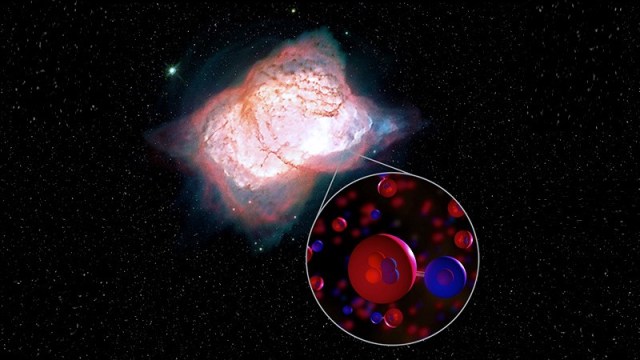

The gharial crocodile in India, for instance, is on the brink of extinction, partially due to sand mining practices that have destroyed its nesting sites. The same is true of the Ganges River dolphin. When dunes or other coastline barriers are mined for their sand, sometimes nearby communities can be flooded. Ironically, although deserts have an abundance of sand, the sand grains found in such environments have been rounded by the wind, causing them to bind poorly and rendering them ineffective for use in concrete.

Sand mining is regulated, but its difficult to enforce regulations when it is so easy for individuals to gather sand in their local river. For this reason, India’s sand mafia differs from a traditional mafia in the sense that its much more distributed and less hierarchical. Illegal sand mining can be carried out independently or as part of small group of sand miners. One can participate in the illegal sand mining industry by mining directly, transporting the material, accepting bribes to ignore the law, acting as a middleman between the miners and developers, and so on.

A Ganges River dolphin swimming near Bangladesh. Image source: worldwildlife.org

However, sand mining also includes individuals we would think of as more traditional gangsters. For instance, consider how one man who owned an illegal sand mining operation described encounters with the police in an interview with The New York Times: “If there are a lot of police and only a few men, then we run. […] If the police are few and the men are many, then we get into it with them. We fire shot for shot.”

Violence is not uncommon in the illegal sand mining trade. Another individual, Paleram Chauhan, 52, was shot dead after speaking out against the sand mining that was going on in his village. His son, Akaash Chauhan, decided to continue his father’s crusade against the illegal sand mining industry. “My father’s fight has become my fight,” he told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. “Sand mining is ongoing — my father was against it, I am against it and so is my family.”

Indian laborers extract sand from the Meshwo river bed, near Mahemdabad.

Photo credit: SAM PANTHAKY / AFP / Getty Images

A lucrative industry

There’s good reason illegal sand mining is so violently defended. Conservatively, the illegal sand mining industry is worth $250 million a year, which translates to significant sums for workers who would only receive poor wages elsewhere. One individual who had worked at a bank was paid 400 rupees per day, or $5. Working in the middle of the night, mining and carting away sand netted him five times that amount, a sum of money that goes a long way in impoverished Indian communities.

Sand mining is a necessary practice that will continue so long as there are buildings to be made. In India, there is enough sand to do so in a sustainable way when mining is targeted at the right areas, but corruption makes enforcing industry regulations quite difficult. At humanity’s current population and industrial scale, even extracting something as ubiquitous as sand can have drastic environmental consequences, underscoring the need for effective regulation.