Why do we so consistently underestimate progress?

This article is republished with permission of The Progress Network. Read the original article.

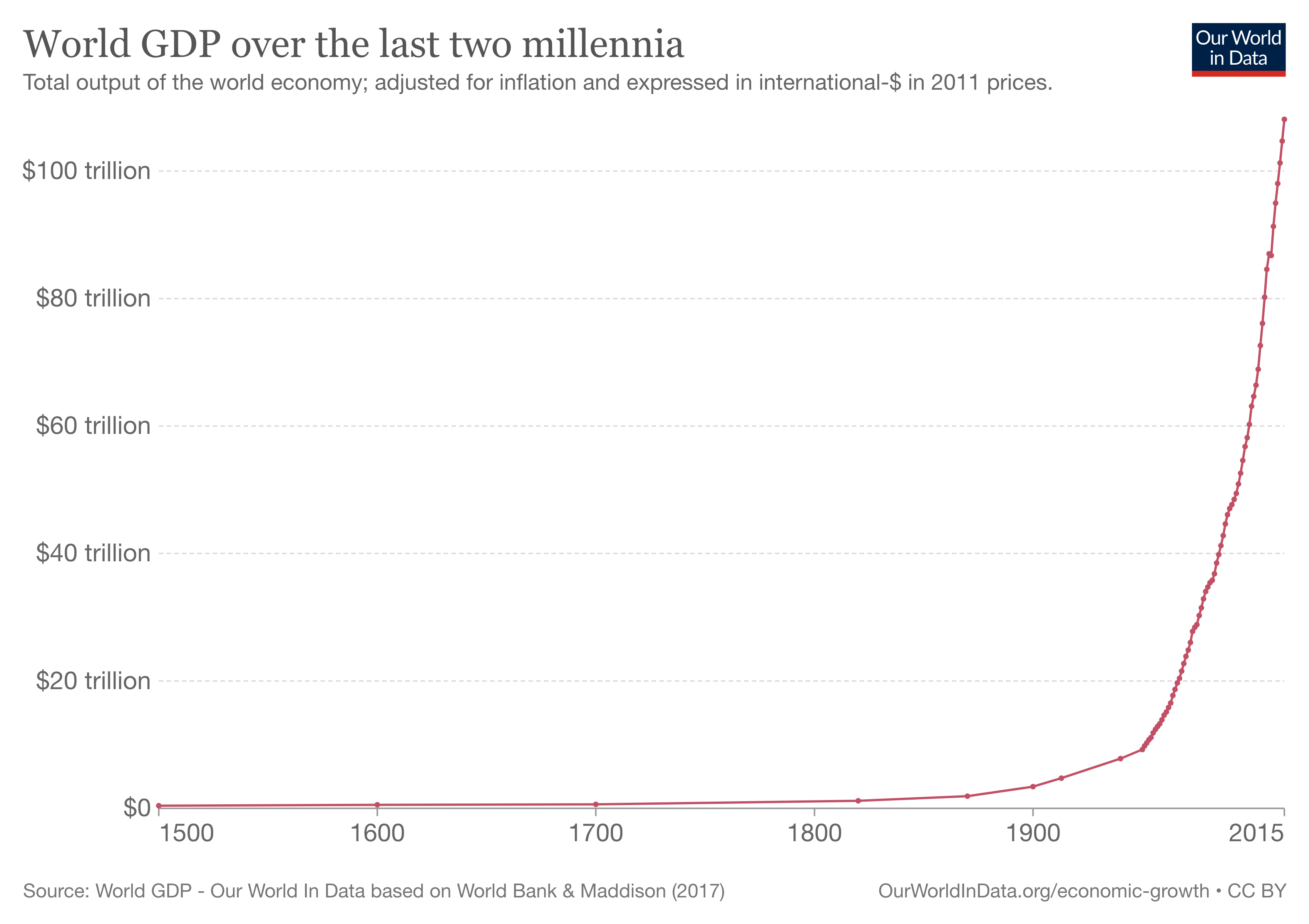

Progress that is both rapid enough to be noticed and stable enough to continue over many generations has been achieved only once in human history: right now. Around 1800, humanity made a stark turn from misery and stagnation to prosperity and progress. This is a truly unique moment in time, and yet one that most of us aren’t even aware of.

It’s not just GDP. Poverty and child mortality rates over the last two centuries have dropped while literacy and vaccination rates have climbed. Many more people live under democratic forms of government. The world today finds itself atop this upward march of progress, but we think we’re going the other way. When surveyed, only 6% of Americans think the world is getting better, while in Australia and France the figure stands at an even more ominous 3%.

This is a sad state of affairs; we are lucky enough to have found ourselves living through this incredible point in human history, and yet we have no idea that we’re even here. Progress is rapid and powerful, and yet invisible—a “secret, silent miracle,” as Hans Rosling, the Swedish health professor and data visionary, put it. Why is progress so hard to see?

If we follow the long-term trendlines, we soon realize that we are living through a time of spectacular progress. It is not long-term trendlines, though, that shape people’s worldviews. It is headlines. And the deluge of them that we subject ourselves to daily leaves us drowning in negativity. Images of war, poverty, disease, and scandals fill the news, which is designed to inform us about aberrations from the norm, not the norm itself, and to appeal to our instinct for gossip and drama, rather than our desire to understand the world. (Rosling, for one, compared forming a worldview from the news to forming a view of himself by looking at his foot.) Progress, on the other hand, accumulates over time and thus is rarely dramatic enough to be covered by the media—even though, as the founder of Our World in Data, Max Roser, has said, the media could have run the headline “137,000 people lifted out of extreme poverty in the last 24 hours” every day between 1990 and 2015.

Humans are also linear thinkers. Our brains are wired to extrapolate data based on straight lines, not exponential curves, which leads us to dramatically underestimate progress, particularly in the long-run. In 1901, Wilbur Wright proclaimed to his brother Orville that manned flight would be at least 50 years away. Two years later, on October 19, 1903, The New York Times went further and published an article that said “to build a flying machine would require the combined and continuous efforts of mathematicians and mechanics for 1-10 million years.” Just ten weeks after this, on December 17, 1903, the Wright brothers achieved man’s first flight by airplane, stunning the world. Space exploration, too, was underestimated by The New York Times in 1920. One piece mocked a professor’s idea of sending a rocket to the moon, saying that he lacked “knowledge ladled out daily in high schools.” After the moon landing in 1969, the Times issued a correction.

To understand the difference between exponential growth and linear growth, consider this: If you were to place a drop of water in the middle of London’s Wembley stadium, wait for a minute, place two drops, wait for another minute, place three drops, then 4 drops and so on, it would take 11 years to fill the stadium. If instead the number of drops increased exponentially; in other words, you place one drop, then two drops after a minute, then four, then eight and so on, the stadium would be full by the 48th minute. Exponential growth is everywhere, powering progress over recent decades through Moore’s law, the observation that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles every two years, a pattern that now means we have more processing power on our smartphone than the entirety of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had for the moon landings.

Humans also have a predisposition toward negativity that is wired deep into our DNA. Until recent times, Homo sapiens were the underdogs of the savannah, under constant threat from the risks of predators, disease, and starvation. Being able to notice and pay attention to these threats was an evolutionary advantage—the pessimists survived, and the optimists died. We have since left the savannah and its perils and built civilizations. Yet a quick glance at the evening news will remind you how we are still plagued by this negativity bias.

The amygdala, a part of the brain dedicated to processing risk and fear, receives sensory information and stimuli before they’re sent to the cerebral cortex, meaning a fear reaction is initiated even before we can consciously process what is happening—an “amygdala hijack,” as the psychologist Daniel Goleman described it. Since today’s risks are, for many, no longer short-term dangers to the individual—think predators and starvation—but rather longer-term threats to the collective—like economic or political blowups and nuclear weapons—kneejerk fear and urgency, instead of helping us, may instead be a hindrance to assessment of and response to complex circumstances. Evaluating today’s risks often calls for sober judgment and consideration of the potential opportunities, imaginative fixes, and upside of a situation.

Biologist Paul Ehrlich claimed in his 1968 book The Population Bomb, for instance, that given growing population trends, the battle to feed humanity was over. He predicted that by the 1980s four billion people would die of famine, even claiming that India was so close to collapse that it should not even receive food aid, since this would only prolong the pain. This Malthusian fear mongering could hardly have been more wrong. World calorie supply per person has increased by over 25% since 1968 and the annual death rate from famine is now just 1% of what it was in the 1960s, all despite booming populations. Imagine if food aid to India had been cut off, as was suggested?

If there is any lesson to learn, it is this: a radically better future is far more likely than we often assume. The technologies and ideas that will take us there are ones that we cannot yet imagine. To believe in progress is to believe in the extraordinary, the unconventional, and the unknown. Perhaps this is the last reason we underestimate progress. We perceive it as naïve and fanciful to place confidence in yet undefined future breakthroughs. But sticking to the known and the proven will result in one thing with absolute certainty: undue pessimism.