Global emissions slowed down in 2019, but still reached a record high

Shutterstock

- A series of studies concluded that the growth in emissions have slowed to 0.6 percent in 2019.

- Despite this, 2019 was another record year, with 37 gigatons of CO2 released into the atmosphere.

- The U.S. and E.U. actually reduced their emissions in 2019, but this was offset by the growth in emissions from the developing world. The findings highlight the importance of developing renewable energy infrastructure in these countries.

New research offers the very dimmest of good news in the global effort to restrict the rise in temperatures to below 2°C in accordance with the Paris Agreement: The growth in emissions in 2019 slowed down to an estimated 0.6 percent, as compared to 2018’s 2.1 percent and 2017’s 1.5 percent.

Regrettably, this modest growth rate in emissions still meant that 2019 was another record year, with around 37 gigatons of CO2 released into the atmosphere. Although the reduced growth rate could indicate a turnaround, the researchers anticipate that the further growth of developing countries will ensure that further rises in emissions are likely in 2020 and beyond.

The findings are discussed in three new articles in Earth System Science Data, Environmental Research Letters, and Nature Climate Change. While the results are disappointing, they do provide insight into where further reductions need to be made and there are small morsels of good news tucked away within the data.

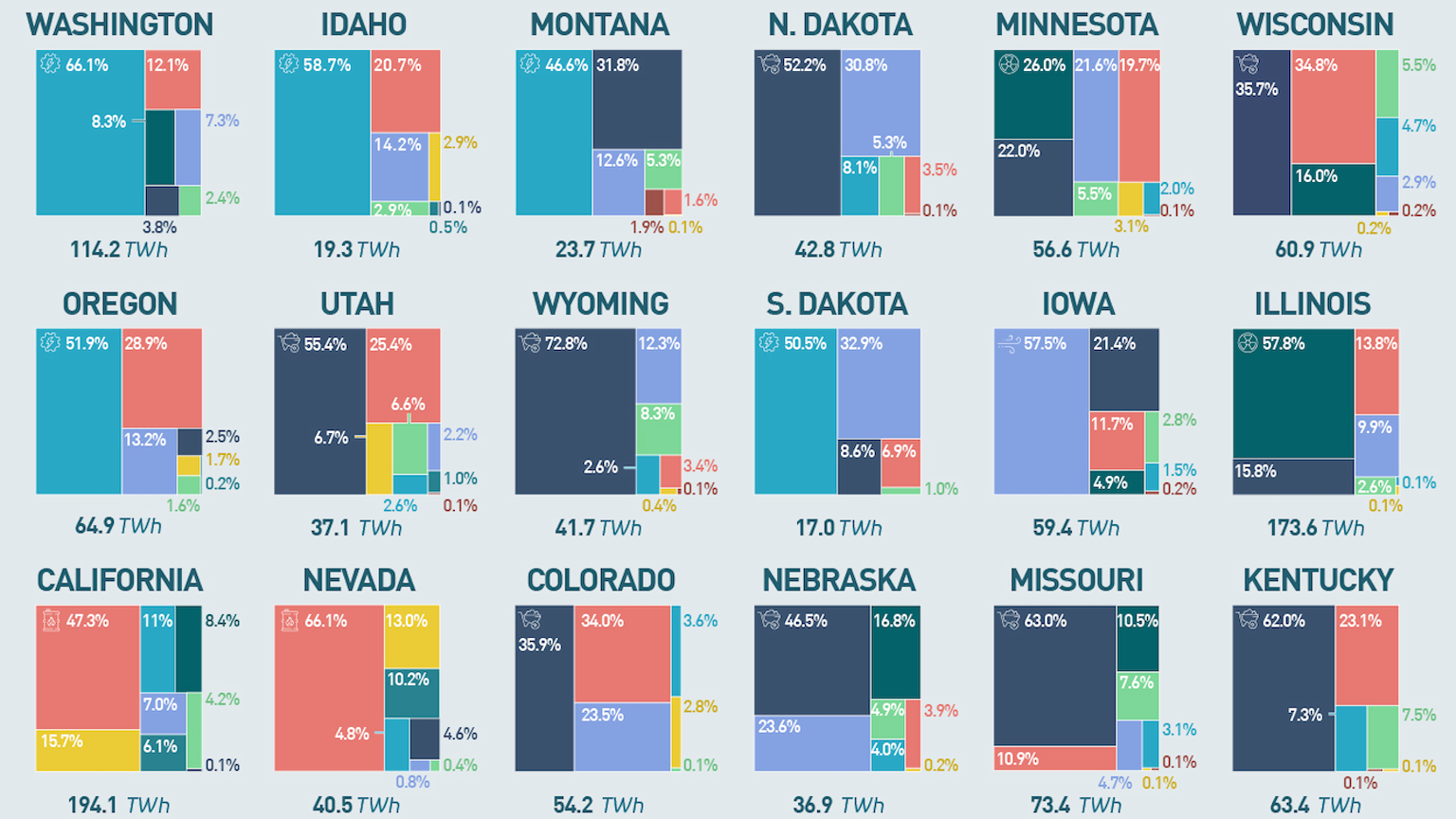

For instance, emissions from the U.S. actually decreased by 1.7 percent in 2019. While there is no such thing as a clean fossil fuel, some are worse than others. The U.S. has done a tremendous job moving away from the use of coal, a particularly dirty form of fuel. Since peak usage in 2005, the U.S. has cut its coal emissions by 50 percent down to levels not seen since 1965. Coal plants are increasingly retiring, and no new coal plants are being constructed.

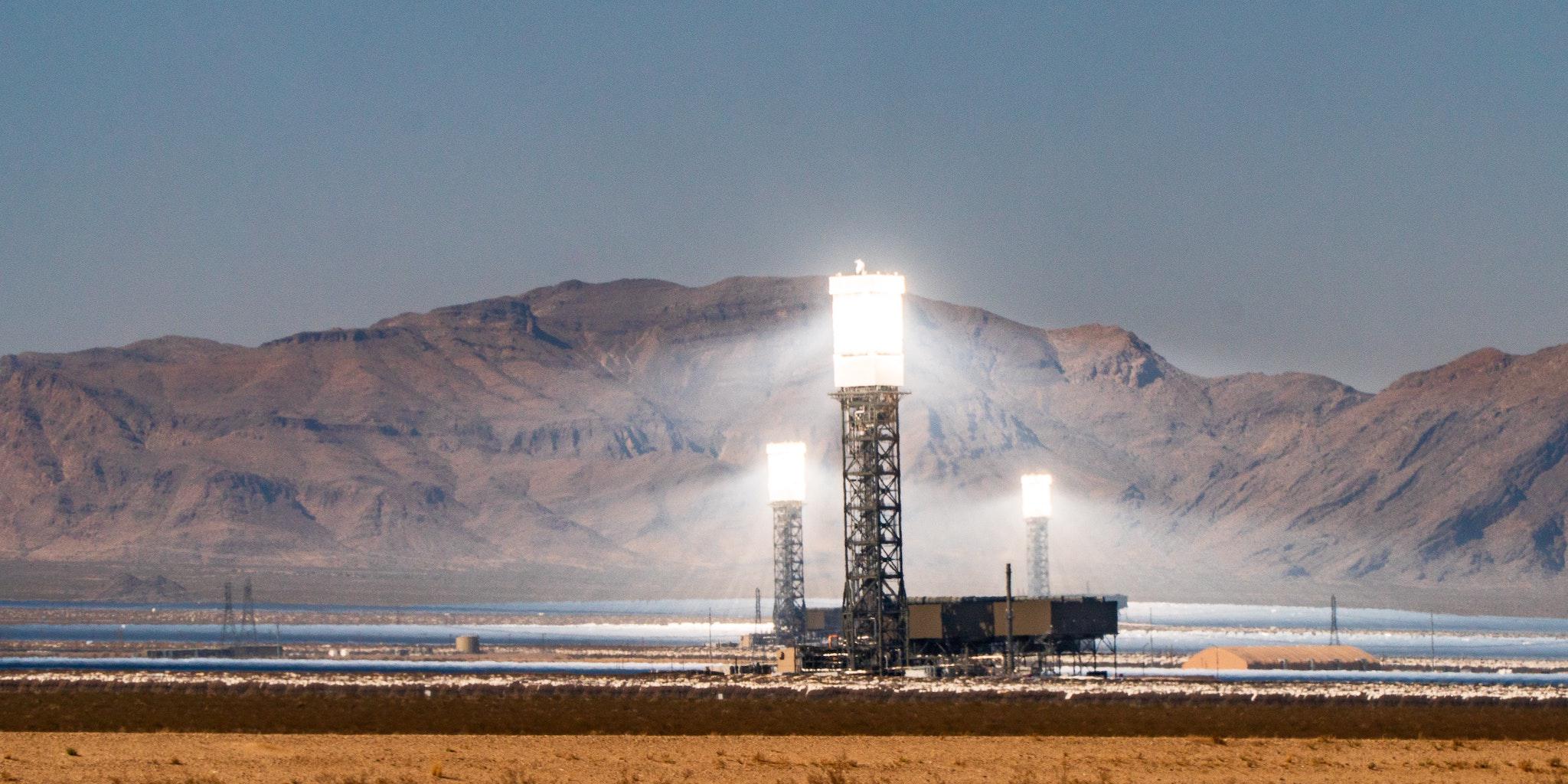

However, coal usage in the U.S. is not being replaced by renewable energy for the most part; rather, natural gas is stepping in to take its place. Natural gas is sometimes construed as a “bridge fuel” that countries can rely on during their transition to renewable energy, but it only serves that role if that transition actually occurs. Fortunately, wind and solar generation in the U.S. did grow by 8 percent and 11 percent in 2019.

The U.K. and E.U. is doing even better: E.U. emissions dropped by 1.7 percent and reduced coal emissions by 10 percent. But while the U.S. has primarily replaced coal use by natural gas, the U.K. has made up the difference with a 50-50 split between natural gas and renewable energy.

Developing countries like India and China have offset these reductions, however, increasing their emissions by 8 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively. It’s important to remember that the U.S., E.U., and China together account for more than half of all global emissions in CO2, so any reductions in emissions from these three countries is excellent news.

Solar panels are installed outside of Mumbai.

Pramod Thakur/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Transitioning to renewables across the globe

Developing countries face a particular challenge in reducing greenhouse gas emissions — their people want a decent quality of life, and the easiest way to deliver the energy that quality of life requires is through fossil fuel usage, especially coal.

In developing countries, the infrastructure and technology necessary to support renewable energy isn’t always in place. Developing and maintaining the kind of infrastructure necessary for renewable energy is far more demanding than it is for the infrastructure needed to exploit coal as an energy source.

When regions like the E.U. and U.S. were developing, however, renewable energy didn’t exist. Thus, reducing emissions from developing countries is feasible, although it will likely require international support. In fact, despite their on-going development, both China and India are developing their renewable energy capacity at an incredible pace — China is actually the world’s largest producer, exporter, and installer of solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and electric vehicles. These developments are good, but more effort is needed. In order to preserve ecological diversity and avoid civil unrest in the face of climate change, both developed and developing countries will need to realize greater reductions in their emissions and a more rapid transition to renewable energy.