Controversy: Was the Caribbean really invaded by cannibals?

Theodor de Bry, 1596.

- Columbus and subsequent chroniclers wrote about native peoples in the Caribbean who described being attacked by Carib cannibals.

- One argument against the veracity of these reports has centered on a lack of archaeological evidence that Caribs ever migrated to the Bahamian islands described by these sources.

- A 2020 archaeological study of skulls suggest the Carib would have been well established in those regions by Columbus’ arrival. But some archaeologists disagree.

By October 1492, Christopher Columbus and his crew had been crossing the Atlantic Ocean for two months when they spotted an island on the horizon. The Spaniards were hoping to reach “the noble island of Cipangu,” or Japan — a land rumored to be rich with spices and gold. They instead landed in the Bahamas.

Columbus kept a diary of his trip to the New World. He documented interactions with the Arawak-speaking natives, describing how he and his crew forcibly took some of them on ships to help search for Japanese and Chinese riches. Besides the mistreatment of natives, one theme in his entries has long been the subject of debate: marauding cannibals.

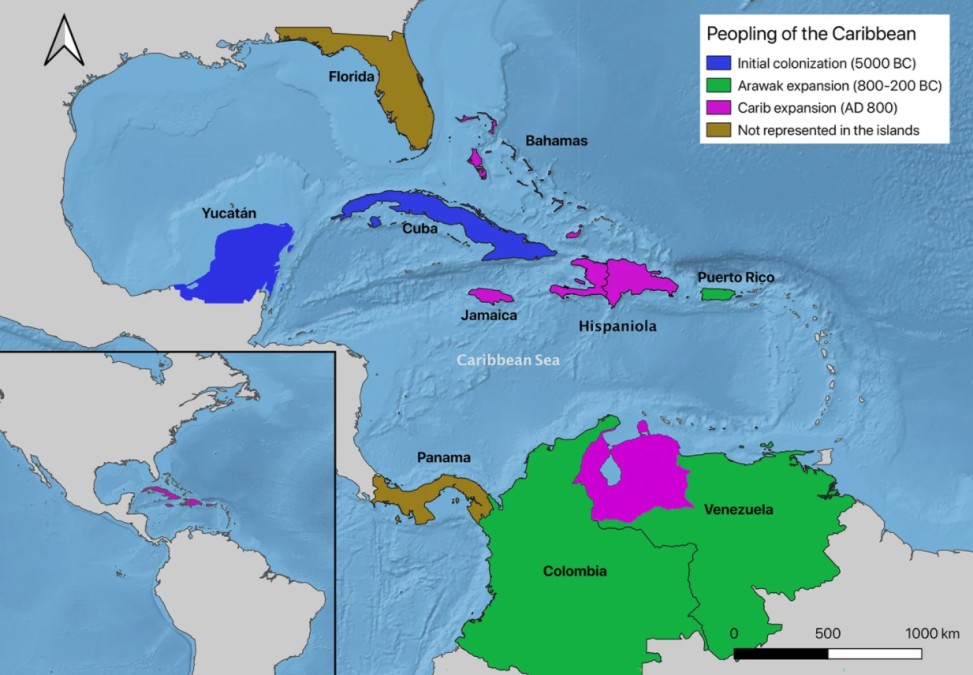

Columbus wrote multiple entries about Arawak natives who said they had been attacked by Caribs — a people originally from the Northwest Amazon who recent research suggests were some of the earliest settlers in the Caribbean.

“I saw [Arawaks] who had marks of wounds on their bodies and I made signs to them asking what they were, and they showed me how people from other islands nearby came there and tried to take them, and how they defended themselves,” Columbus wrote on his first day in the Bahamas.

Another entry describes how a group of Arawaks — who were traveling between islands on one of the Spanish ships — reacted when they saw an island they believed to be inhabited by Caribs:

“[The Arawaks] said that this land was very extensive and that in it were people who had one eye in the forehead, and others whom they called ‘Cannibals’. Of these last, they showed great fear, and when they saw that this course was being taken, they were speechless, he says, because those people ate them and because they are very warlike.”

A similar entry describes how, upon seeing a certain island, the Arawaks “were speechless, fearing that they would be eaten, and [a crew member] could not calm their terror; and they said that the people there had only one eye and the face of a dog.”

But despite these accounts, many researchers think there were no cannibalistic invaders, arguing that Columbus must have been mistaken, lied to, or perhaps even lying himself.

History or harmful myth?

At the dawn of the 16th century, the question of whether large-scale cannibalism was practiced in the Caribbean was tangibly important for the native peoples. After all, Columbus’ reports of Carib cannibals ultimately led Queen Isabella of Spain to issue a 1503 decree stating that natives could be enslaved for practicing cannibalism.

Researchers have argued that the law made it easier for the Spanish to enslave large numbers of native peoples by simply branding them as cannibals, and that it more broadly contributed to European conceptions that native peoples were “savages.” Justin Winsor, a historian of Columbus, wrote that the Spanish used stories of cannibalism to “overcome the earliest humane protests against the slaughter of the natives and their deportation for slaves.”

Today, some historians argue that tales of cannibalism in the New World are still used to obfuscate or justify the violent history of European colonialism and Columbus, a figure who exists in the public imagination between the poles of brave explorer and evil colonizer. Ideological persuasions arguably influence researchers’ bias when it comes to the question of Carib cannibalism.

So, what is the evidence? Beyond the Spanish accounts, other reports suggest the Caribs — who, to be sure, were a loosely defined group of multiple cultures that inhabited both the Caribbean and South America — did practice cannibalism in some forms. While visiting a Carib village in Venezuela near the Guarapiche River, the 17th-century French missionary Pierre Pelleprata described how a Carib came to him with a gift: “He passed me a basket, in which there was the hand and foot of an Arawak, and then invited me to eat.”

That was one of the accounts listed in Neil L. Whitehead’s 1984 paper “Carib cannibalism. The historical evidence,” which concludes by saying that “a close reading of the sources strongly indicates the existence of cannibalism among the Caribs.” But Whitehead was careful to distinguish limited ritualistic forms of cannibalism, such as eating a small amount of the cooked flesh of an enemy, from the more lurid descriptions from the Spanish, which he said mostly amounted to “imperial propaganda.”

As far as Columbus’ reports of Carib cannibalism in the Bahamas, critics have noted that neither he nor his crew ever witnessed a Carib practicing cannibalism; most of the accounts were based on stories they heard from the Arawaks. Columbus himself noted that he had “found no monsters.”

On the archaeological side, skeptics of the cannibalism narrative have argued that there is no evidence that the Carib people ever even made it to the islands Columbus said they inhabited. Therefore, according to these critics, the cannibalism story is most likely fiction.

But recent research suggests the Carib people did migrate to those islands, and generally migrated throughout the Caribbean earlier than previously thought. While the controversial results do not confirm that the Carib practiced cannibalism, they do support the possibility.

Examining Caribbean migrations

The goal of the study — published in Scientific Reports in 2020 — was to determine from where different groups of people migrated into the Caribbean. Prior archaeological research relied mainly on artifacts like pottery to establish migratory patterns. But the recent study looked at “faces, instead of islands,” using imaging software to analyze cranial features of more than 100 skulls from people who lived in the Caribbean from about 800 to 1542 AD.

The goal was to use the cranial data — which the researchers described as a “genetic proxy for examining” different populations — to determine how closely related the people were to each other and to uncover any patterns related to migration.

The results showed there were three distinct Caribbean groups, one of which was the Carib. The cranial analyses suggest the Carib would have been well established in the Bahamas by the time Columbus arrived, and therefore, they could have battled with the Arawak. The researchers noted that their overall finding is supported by previous discoveries of Carib-associated pottery on Bahamian islands.

“The big idea is that anthropologists thought there were two waves of pre-Columbian migration into the Caribbean,” Ann Ross, lead study author, told NC State University News.

“One that came up from South America into the Lesser Antilles, like Grenada and Guadeloupe, and another that came from the Yucatán up through Cuba. What we’ve found indicates that there was a third wave, separate from the others […] The Carib people were the third wave. Until now, it was thought that the Carib didn’t make it past Guadeloupe. But our work indicates they made it as far as The Bahamas.”

Controversial claims

The study — which briefly mentioned the debate over Carib cannibalism — sparked controversy among archaeologists. A paper published in August 2021 described the research as “limited by sampling issues; problematic methodological choices; poorly supported archaeological claims; and inappropriate conflations of biology, ethnicity, artefacts, and questionable historical accounts.”

The critics also called out the original paper’s mention of Carib cannibalism:

“We find this especially concerning as it may harm contemporary Island Carib descendant communities (the Kalinago of the Lesser Antilles and Garifuna [also known as the Black Caribs] of Central America) and South American communities, who, through either their connection with the Cariban language family or ‘Carib’ designation, are affected by claims of Carib cannibalism.”

The authors of the original study responded to the critics, accusing them of misunderstanding the study’s methodology and main goals. The response did not mention cannibalism, but the authors noted that their study was “a community collaborative project whereby archaeological research and excavations have been approved and provided by present-day community members in the Bahamas to elucidate the prehistory of the Caribbean.”

Christina Giovas, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University and one of the critics of the original study, said in a statement:

“The idea that ancient Caribbeans were cannibals still persists in popular imagination, but there has never been any scientific evidence showing they practiced cannibalism, despite the fact that we have really good archaeological techniques to detect this.”

Ross, lead author of the 2020 study, told The Daily Mail that the criticisms represent “gross misunderstandings” of the work and seem like “performative allyship.” To be sure, none of the authors of the original study claim their results prove that Carib people practiced cannibalism. But unlike writers and researchers who label the cannibalism narrative as outright false or in need of debunking, they leave open the possibility that the reports from Columbus and other chroniclers could contain some truth.

“Maybe there was some cannibalism involved [between the Caribs and Arawaks],” William Keegan, a coauthor on the 2020 study and curator of Caribbean archaeology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, told the Florida Museum of Natural History. “If you need to frighten your enemies, that’s a really good way to do it.”