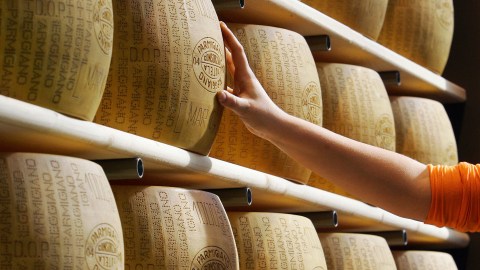

This bank in Italy accepted cheese as collateral. Here’s why.

FILIPPO MONTEFORTE/AFP/Getty Images

- When giving out a secured loan, most banks ask for a form of collateral to recoup their losses in case the borrower defaults.

- Most people put up their homes as collateral, but one bank in Italy accepts wheels of delicious, sharp, and valuable cheese.

- It might seem bizarre, but it’s not the first time unusual items have been used as collateral.

If you were to take out a loan for buying a home — a mortgage — you would offer up your house as collateral to the bank. If you can’t make your payments, the bank will take your house back to recoup its losses. If you were a farmer, your collateral might instead be the tractors and combines necessary to conduct your business. Normally, this stuff doesn’t exactly make for great party conversations.

However, if you were, say, a small business owner in the Italian city of Reggio Emilia, you could ask the bank Credito Emiliano for a loan. Credem — as the bank is informally known — will accept traditional assets as collateral as well as something a bit more unorthodox: wheels of Parmigiano-Reggiano, also known as “The King of Cheese.”

Photo credit: FILIPPO MONTEFORTE/AFP/Getty Images

The high cost of good cheese

Real Parmigiano-Reggiano can only be made in a few provinces in Italy, specifically Parma, Reggio Emilia, Bologna, Modena, and Mantua. Similar cheeses produced outside of those regions are known as parmesan, but they don’t hold a candle to the real stuff. The roughly 80-lb wheels of Parmigiano-Reggiano have a deliciously sharp, nutty, and fruity taste, produced according to a strict set of rules that define the cow’s diet, how fresh the cow’s milk can be, what ingredients can be used, how long the cheese can be aged, and other stipulations. The result is an incomparable taste and a lot of value: One wheel of Parmigiano-Reggiano can range anywhere between $900 and $2,500.

The trouble is, producing and aging the cheese is a delicate process. Parmigiano-Reggiano can take between 12 and 36 months to fully age, and a lot can go wrong in the interim. Under the wrong conditions, the cheeses can sweat, bubble, or crack. Too many cracks in the exterior of the wheel and the sharp and savory cheesy interior can spoil.

Considering their value, fragility, and the time they take to produce, farmers selling wheels of Parmigiano-Reggiano are often forced to sell their cheeses before full maturation in order to get an influx of cash. A lot of time and effort is wrapped up in the cheese, and if a farmer has a bad year selling other products, they might have no choice but to liquidate their cheesy assets before they had fully matured.

A worker inspects a wheel of Parimigiano-Reggiano by thumping it with a hammer. By listening to the sound it produces, he can determine if the wheel contains any internal fissures, which would reduce the value of the wheel. MARCO BERTORELLO/AFP/Getty Images

A win-win

Here’s where Credem comes in. Farmers supply the bank with their aging cheese wheels in exchange for loans amounting to 70 percent to 80 percent of the wheels’ total value. In this way, farmers have immediate access to the cash they would otherwise have gained a year or two or three later.

Not only that, but Credem stores the cheeses in the Tagliate General Warehouse. There, 300,000 wheels of cheese age under a carefully controlled environment and are regularly inspected by experts to assess the quality of the cheese. Outside of the Credem warehouse, about 10 percent of Parmigiano-Reggiano wheels degrade due to environmental damage, which is a fairly significant chunk considering their value and long maturation period. At Credem’s warehouse, only about 1 percent of the cheeses degrade.

“From the bank’s perspective, it becomes almost risk free,” said Harvard Business School (HBS) assistant professor Nikalaos Trichakis in an interview with Forbes. Along with Professor Gerry Tsoukalas, Trichakis authored a case study of the unconventional bank for HBS. “They have the collateral in their possession the whole time it is aging. So the moment they see some issues — like bubbles, for instance — they can say, ‘Oh, that collateral isn’t worth as much as we thought.’ And they can immediately call up the producers and say, ‘Listen, you’re under water here.'”

Overall, it turns into a much-improved scenario for farmers. Farming can be an extremely volatile industry, especially in Italy, where most farms are small- to medium-sized businesses and lack the resilience that consolidating into a larger entity might provide. “They remain fragmented due to Italian tradition,” says Trichakis. “Most of these families have been producing cheese for centuries and take pride in what they do, resisting becoming part of larger corporations.”

Other odd kinds of collateral

Credem might seem like an outlandish institution, but other banks have accepted unique forms of collateral before. Prior to Prohibition, banks accepted whiskey as collateral for many of the same reasons Credem accepts cheese: Whiskey needs to mature over time, is sensitive to its environment, and is worth quite a bit. Another bank in Hong Kong accepts designer handbags, several accept thoroughbred horses, and when one Spanish bank sought a loan from the European Central Bank, they put up Cristiano Ronaldo and a teammate as collateral.

Ultimately, anything that holds and retains value and can easily be liquidated (although I’m not sure how “liquidating” Rinaldo would work) can be used as collateral. It’s just that some banks interpret these requirements a little more flexibly than others.