“Unemployment for all”: The ideology of the anti-work movement

- The labor market is changing, and the pandemic changed how we view work. The anti-work movement represents a shift in how we view the workplace — where work should be fulfilling and not drudgery.

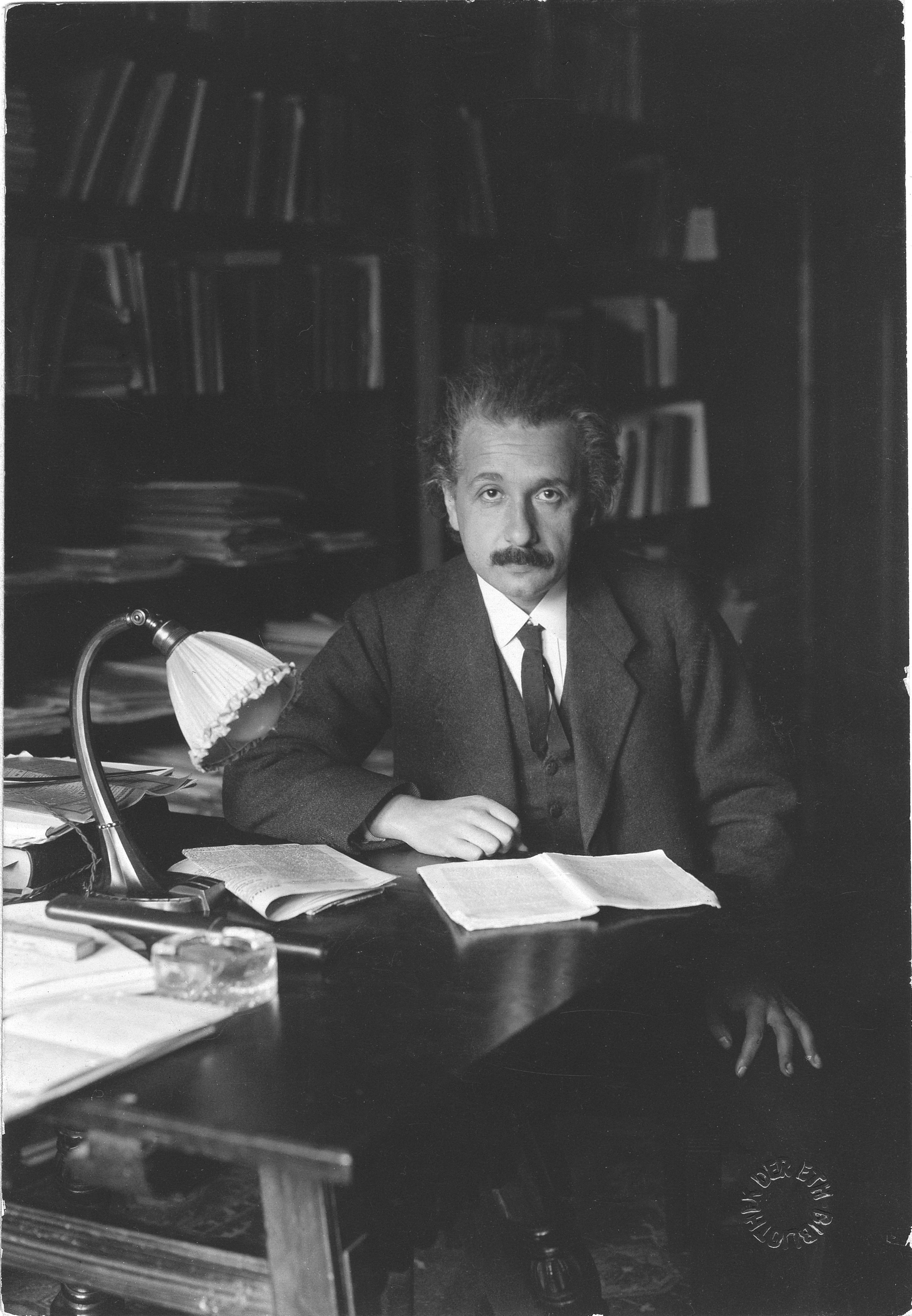

- Bertrand Russell argued that there’s no reason why we’re working so hard these days and that in “leisure” time humans create the most brilliant things.

- But is anti-work reflected in the general public or merely the indulgent whim of some privileged few who have the luxury of being able to quit their job?

The most common surname in Australia, Britain, New Zealand, Canada, and the U.S. is Smith. A smith is, historically, a job title — a gunsmith, blacksmith, or goldsmith. In Germany, the most common name is Mueller (miller). In Slovakia, it’s Varga (cobbler). All over the U.S., you will find Hunter, Skinner, Weaver, Barber, Cook, Mason, Brewer, and Gardener. Our surnames tell a fascinating etymological tale about our forebears. And what this particular tale tells us, is that occupations mattered a lot. They mattered so much that they defined who you are.

Many cultures have a version of a “good works” philosophy. This is the idea that the jobs we do, and the sweat and toil we put into a thing, define who we are. If the devil makes work for idle hands, then good, old-fashioned hard work will make us saints. We give life meaning in what we do and are most contented after a job well done.

Yet, there’s a growing portion of society who didn’t get the memo. With the rise of the “Anti-work movement”, the surnames of tomorrow might well be Mr. Quitter, Mrs. Resign, and Dr. Remote.

The anti-work Movement

The Antiwork subreddit has 2.5 million subscribers. It’s a place for people who, “want to end work, are curious about ending work, [and who] want to get the most out of a work-free life.” If you read what some of the old timers on the forum have to say, you’ll see them complain about how it’s a far cry from what it once was. Today, it’s mainly a depository of memes, rejection letters, and, “my boss is an A-hole” threads. When it first started, it spawned an entire movement.

The very term “anti-work” is somewhat misleading. The anti-work philosophy is one which is not against working or effort, but rather the exploitation of the labor force. It rejects the fact that we all need to work ourselves to the bone – risking burnout and cardiac arrest – to fuel some constantly growing, omnivorous system. It’s not even against capitalism, per se, but rather the kinds of jobs (and the kinds of bosses) that see humans as resources. Anti-work is about imagining a world where we do not have to sell our labor to survive. We’ve all internalized a narrative that we “must” exchange hours of tedious employment for the means by which to pay rent, buy food, to pay for electricity. In many ways, anti-work is better understood as pro-fulfilling work.

In praise of idleness

If ever there were a philosophy of anti-work, it’s found in Bertrand Russell’s essay, In Praise of Idleness. In the essay, we can identify three distinct points:

The first is to take on the idea that “work will make you better.” Workaholism is a pernicious hangover of old Calvinistic theology. According to the sociologist, Max Weber, the reason that so much of the Western world (and its imitators) insist on working so hard, goes back to the Protestant idea that good works will save your soul. If only a finite, select elite will be going to heaven, working hard and being seen to be hard-working, will get you into God’s good books. But, as Russell puts it, “A great deal of harm is being done in the modern world by belief in the virtuousness of work.” The idea that we should work ourselves to death is one which will only ever destroy us. As Russell argues later, this morality of work is no different from the morality of slavery, and, “the modern world has no need of slavery.”

Second, Russell raises the point that the most meaningful work a human can do is one which is born of leisure. When we have time to pursue the hobbies and activities we want, humans can create breathtaking works of art, design world-bettering inventions, and compose incredible music. “Leisure is essential to civilization,” Russell argues, and if we cram a person’s week and headspace with mindless drudgery, we lose the greatness of human creativity.

The final point is to argue that society is so far advanced now, and technology so efficient, that no one needs to work 40-hour weeks, anymore. As Russell puts it, “Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all…What is needed is a new revolutionary movement, dedicated to the elimination of overwork and to the reduction of work to a minimum.” And this was written in the 1930s. Today, we have computer-operated factory lines and artificial intelligence. We have remote working and 5G. It beggars belief that we’re working the same hours our forebears were.

The times, they are a-changin‘

When the pandemic hit, almost all of us were suddenly out of the office and wallowing in the pajama-clad luxury of video calls and Spotify on loud. The entire way we did work changed. When the foghorn signaled the return to the factory, it turns out that a lot of people simply didn’t come back. The vast majority of these were those at or near retirement age. But the number of people ages 16 to 25 with no jobs, education, or training increased markedly. Between 2004 and 2022, there was a 16% reduction in 16- to 19-year-olds working, and nearly 7% among 20- to 24-year-olds.

The ease of working from home has stuck. According to one Gallup poll, more than half of workers would look for a new job if their current employer asked them to work in the office. The great shift to remote or hybrid working has people recognizing how important it is to be at home with the family, how long that commute actually was, or how unnecessary being at a desk in a distant district really is.

But, in many ways, anti-work and “The Great Resignation” are born of luxury. With unemployment rates dropping around the world, there will be fewer well-paid jobs, so job-hopping might become harder. What’s more, not everyone will have the savings — or a parents’ home — to fall back on as they wallow “in between jobs.” On the antiwork subreddit, when someone announces they’ve quit their job, invariably the first comment is, “Sign on to social security.” While working to survive might be an awful way to run a society, a lot of people will find resorting to benefits a little galling. And finally, with an energy crisis and a looming recession, many people will be returning to the “work to survive” mindset that Russell attacked. A job, any job, is good in the current economic climate.

So, where do you stand on the anti-work movement? Are they the feckless, lazy children of privilege or the brave vanguard of a utopic upheaval?

Jonny Thomson is our resident philosopher and the author of The Well, a weekly newsletter that explores the biggest questions occupying the world’s brightest minds. Click here to subscribe.