Did war help societies become bigger and more complex?

- About 10,000 years ago, civilization began to develop at an exponential rate.

- Scholars have often explained this growth through two broad theories, one focusing on agriculture and the other on conflict.

- This year, researchers looked at statistics of ancient empires to determine which of the two was more important.

If you were to plot the development of human civilization — defined by population size as well as economic and cultural output, among other factors — you would find that development is not linear but exponential. For tens of thousands of years, people lived in the same basic social organization. But then, around 10,000 years ago, everything changed: In a small period of time, hunter-gatherers settled into villages. Those villages then grew into cities, those cities into kingdoms, and those kingdoms into nation-states.

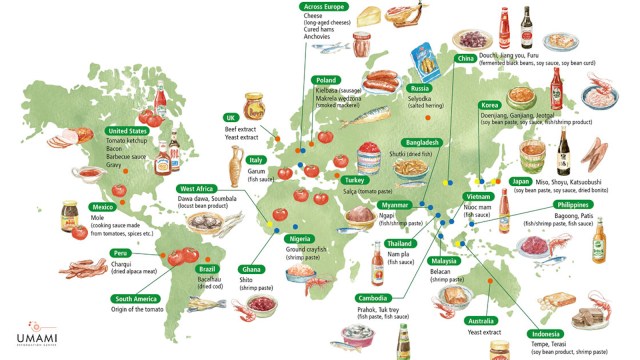

Scholars of various academic disciplines — including history, economics, and sociology — have long searched for the root cause of this development. Currently, they are divided between two theories: one functionalist, the other based on conflict. The functionalist theory, which emerged in the 1960s, focuses on a society’s ability to navigate organizational challenges, like the provision of public goods. According to this theory, trade, healthcare, irrigation systems, and, above all, agriculture were the key factors that allowed civilization to evolve into its current form.

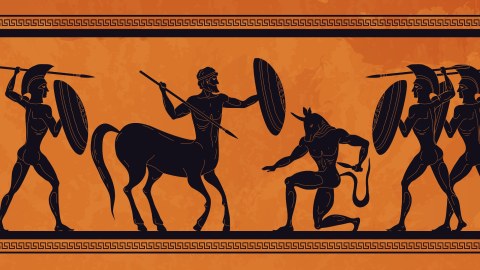

Conflict theory, which is much older than its functionalist counterpart, takes a different approach. It is concerned not with a society’s ability to solve problems related to food supply and public health, but its ability to fight internal and external threats in the forms of class struggle or war. Conflict theory is based on biology; just as the evolution of animal species is governed by that of their predators, so too is the sociological development of any given society kept in check by the military might of its closest enemies.

While scholars view agriculture as crucial to sociological development, they often don’t know what to make of war. “The majority of archaeologists are against the warfare theory,” Peter Turchin, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, told Science. “Nobody likes this ugly idea because obviously warfare is a horrible thing, and we don’t like to think it can have any positive effects.” Undeterred by this widespread bias, Turchin has spent much of his career researching the historical significance of war, including military technology.

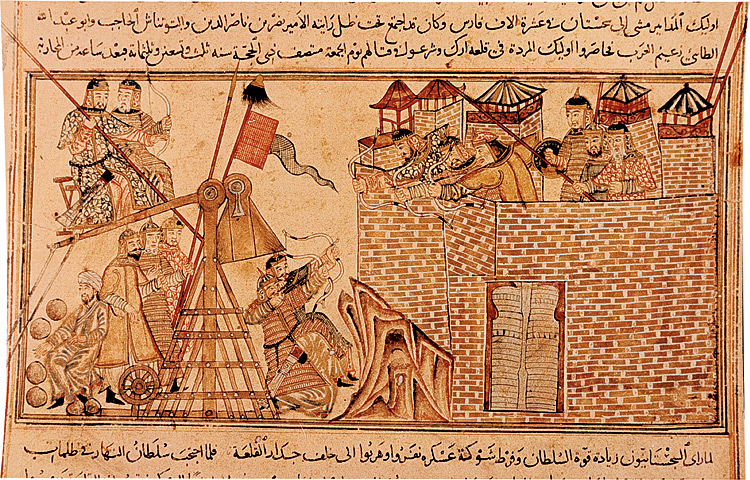

Earlier this year, Turchin put together an international team of researchers to find the most important factors in the rise of Earth’s oldest empires. The results of their study, published in the academic journal Science Advances on June 24, suggest that war — specifically, the use of cavalries and iron weapons — was just as, if not more, important than agriculture. This conclusion tosses a wrench into the functionalist framework, though not everyone is convinced.

History in numbers

The origins and purpose of war have usually been studied by artists and philosophers — people who work through experience and logic. Turchin prefers to use data. Raw, concrete, and empirical data. The data for this study was pulled from Seshat: Global History Databank, a digital resource that compiles numerical entries on more than 400 societies. These range from basic details, such as population size and agricultural production, to highly specific metrics, like whether the society in question employed full-time bureaucrats.

Think of the Seshat databank as world history distilled into numbers. From this point, Turchin and his team constructed a complicated but fairly straightforward statistical analysis. They chose social complexity (defined by population size, social hierarchy, and specialization of governance) as their dependent variable and tested its relationship to 17 independent variables. One of these variables was the provision of public goods, which in turn was aggregated from other and smaller variables, like the presence or absence of water supply systems, bridges, and storage sites.

Some of the independent variables, like the one described above, were formulated to test the functionalist hypothesis. Others, like the sophistication and variety of military technologies used by a society, evaluate conflict theory. Another conflict-related variable is the variety and sophistication of a society’s means to defend itself, defined by the amount of resources invested in things like weapons and armor. The role of this variable, according to the study, is to reflect the “cooperative investment in strengthening the group’s military preparedness and effectiveness in the face of existential threats.”

Two variables were found to have a particularly strong correlation with social complexity. The longer a society practiced agriculture, the more likely it was to become socially complex. The same went for military technology, especially the use of mounted combat and iron weapons. Conventional historians had already suspected as much, but now their words are reinforced with statistics. According to Turchin’s study, cavalry increased the maximum size of civilizations by one order of magnitude, from 100,000 to 3,000,000 square kilometers.

This pattern emerges across the world, and is even repeated at certain points of history. When Spanish colonizers brought horses into North America during the 16th century, the average size of native American civilizations increased just as it had in Eurasia centuries ago. Chief among these civilizations was the Comanche Empire, which ruled over the Great Plains as well as parts of Texas and Mexico. Unlike in Eurasia, the so-called “cavalry revolution” did not come to full fruition because it was soon overtaken by another technological innovation: gunpowder.

The role of war, questioned

While Turchin’s study has received a lot of attention from the academic community, not everyone is equally convinced. William Taylor, an anthropologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, told Science.org that he agrees horses were “an agent of social change.” At the same time, he reminds readers that archeologists are still unsure when people first began riding them, and that, as such, the variable may produce a large margin of error when applied to civilizations of the distant past.

Monique Borgerhoff Mulder, a professor of anthropology and human behavioral ecology at the University of California, Davis, also has a bone to pick with the study. Talking to the same publication, she applauded Turchin and his team for “taking an innovative, macrolevel, quantitative approach to history.” But can we really feel confident claiming that variables like cavalry had a noteworthy impact on social complexity when said complexity did not emerge until 300 to 400 years after cavalry became widespread?

The study’s shortcomings are also addressed by the authors. Focusing purely on social complexity, they evidently failed to consider a society’s cultural or even economic complexity. This is no trivial matter, as expressing human development in terms of social relations only means turning a blind eye to the people of sub-Saharan Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific islands — people who lived in communities that, though small in numbers and lacking vertical hierarchical organization, were nonetheless sophisticated in their own right.

On top of all that, Turchin’s statistical model is not foolproof. His conflict-related variables, for instance, fail to explain the rise of the Inca Empire, which managed to encompass a large territory and complicated government structure despite having neither iron weapons nor horses. They did, however, have a domesticated transport animal in the form of a llama. The taming and riding of lamas, the authors speculate, could have given the Incas an edge over other societies in South America, allowing them to grow as large and prosperous as they did.

It’s not that Turchin and his team do not think variables like agriculture, religion, or economy do not contribute to social complexity. Instead, they feel that these variables alone are not sufficient to explain the exponential growth of civilizations that took place over the past 10,000 years. They also suggest that the importance of war to that process need not be interpreted as a bad thing. “The crucial ingredient in this evolution,” explains the aforementioned story from Science, “was competition (…) not violence.”