The famous Stonehenge monument near Wiltshire, England is one of the biggest architectural marvels and unsolved mysteries in history. In terms of its design as well as its construction, the stone structure — erected sometime between 3000 and 2200 BC — is unlike any other ancient monument built in northwestern Europe during that time.

Each stone weighs roughly the same as a juvenile hippopotamus, and to this day, researchers are clueless as to how the monument could have been assembled several centuries before the first archaeological evidence for the usage of wheels in Britain. The inexplicability of Stonehenge has undoubtedly contributed to its popularity, spawning numerous theories about its origins.

Researching Stonehenge has proven challenging, not only because its builders left no writing to explain their intention or procedures, but also because the monument has deteriorated significantly since its creation. Of the 30 standing stones that once formed Stonehenge’s central ring, seven have fallen over and six have somehow managed to go missing.

Stonehenge might have had multiple functions. Archaeological evidence suggests it was used as a burial site, perhaps for members of royalty. In addition, the monument may have also served as a destination for religious pilgrims or a memorial to long-dead ancestors. Recently, archaeologist Timothy Darvill argued Stonehenge actually may have been a giant calendar.

Keeping time at Stonehenge

The idea that Stonehenge was used as a calendar is not exactly revolutionary. It has been proposed several times in the past, though none of the researchers that did so have managed to agree on what type of calendar it could have been. This might seem trivial, but calendars were a huge deal to ancient civilizations, and there were many, many variations.

One of the first people to formulate this calendar hypothesis was British astronomer Norman Lockyer. In his book, Stonehenge and Other British Stone Monuments Astronomically Considered, Lockyer proposed that Stonehenge was designed to represent a “May Calendar” that relied on certain stars to determine and organize the passage of time.

Lockyer was succeeded by Gerald Hawkins, author of Stonehenge Decoded. Hawkins called Stonehenge a “Neolithic computer,” capable of tracking the movement of the sun as well as the moon. The computer’s main task, Hawkins argued, was predicting the occurrence of solar and lunar eclipses — phenomena that held spiritual significance in prehistoric times.

Next was Alexander Thom, a Scottish engineer whose book Megalithic Sites in Britain argued that Stonehenge represented a calendar of 16 months, and that the structure’s main purpose was not predicting eclipses but solstices, moments in the year when the sun reaches its maximum or minimum declination, heralding the change of seasons.

Darvill, whose scholarly article “Keeping time at Stonehenge” was published via Cambridge University Press earlier this month, labeled these previous interpretations “unsatisfactory, as they often use non-contemporaneous elements of the monument, reference astronomical alignments that do not withstand scrutiny, or perpetuate the discredited idea of a ‘Celtic Calendar.’”

In his article, Darvill tries to show that the numerology of the stones that make up Stonehenge suggest they formed not a May or Celtic calendar but a “perpetual calendar based on a tropical solar year of 365.25 days.” Darvill also speculates about the origins of this calendric system, concluding it either must have developed in northwestern Europe or was imported from the Mediterranean.

The structure of Stonehenge

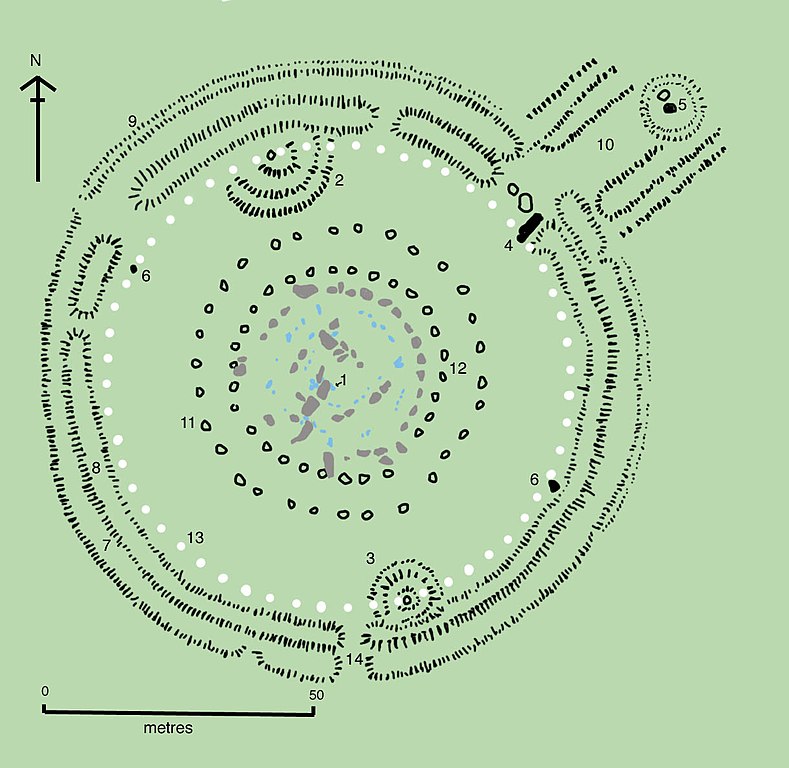

Darvill bases his analysis on remodelings of Stonehenge’s construction that reveal how the monument was put together. The structure’s main elements — the Trilithons, the Sarsen Circle, and the Station Stone Rectangle — are believed to have been erected between 2620 and 2480 BC. The stones came from a common source, and after they were set up, they were never moved again.

According to Darvill’s research paper, “Understanding the sarsen elements as a unified group and recognizing the numerical significance of the elements in each component opens up the possibility that they represent the building blocks of a simple and elegant perpetual calendar based on the 365.25 solar days in a mean tropical year.”

Of the 30 upright stones, only six support lintels: horizontally-placed stones that link the uprights together in a circle. The missing lintels hint at the possibility that Stonehenge was never completed. However, the discovery of empty sockets where these missing lintels would have been placed suggests that this is not the case and that Stonehenge once formed a complete circle.

Once Darvill had sketched an accurate picture of the original construction, he then asked how the elements of that ensemble could have fit together as the “physical expression” of an ancient calendar. His article rejects previous claims that Stonehenge was a lunar calendar, mainly because the structure’s central axis appears to align with the winter solstice.

Different elements of the structure correspond with a different part of the calendar. The Sarsen Circle, Darvill explains, is the core part of the year: each of the 30 upright stones represents a single day within a repeating 30-day month. Twelve rotations of the Circle makes 12 months, which together form a complete solar year.

Of course, a solar year consists of 365.25 days, not 360. To account for this inconsistency, Darvill argues that the Trilithons inside the Sarsen Circle may have represented an intercalary month that rounds up the year. In leap years, the Station Stones — four stones that form a rectangle inside the Sarsen Circle — might have been added to this month, creating a perpetual calendar that can keep track of seasonal changes across extended periods of time.

Midwinter and the purpose of calendars

Darvill’s interpretation of the Stonehenge calendar converges on the winter solstice. This cosmologically significant day, which takes place during the month of December, marks a point in time when the sun reaches its minimum declination. The day of the winter solstice is therefore the shortest day in the year (in the northern hemisphere), heralding the onset of winter.

Calendars organized around the summer and winter solstices were way more common in the past than they are today. In his 725 treaty, The Reckoning of Time, Saint Bede, a Northumbrian monk, states that the pre-Christian New Year used to begin with the midwinter festival of Yule, which in turn corresponded with a midsummer festival known as Litha.

Archaeologist J.P. Mallory and linguist D.Q. Adams provided additional evidence for Bede’s claims, stating that the proto-Indo-European language knew two different words for “year” that expressed the notion of “new season.” This is especially significant considering proto-Indo-European would have been spoken around the time that Stonehenge was erected.

Why did the civilization that constructed Stonehenge feel the need to create a calendar to begin with? Many scholars have argued that ancient civilizations made calendars so that people could plan and keep track of their everyday routine, though this makes little to no sense.

“Although archaeological accounts often rehearse the notion that early farmers needed time-reckoning systems to know when to plant and when to harvest,” Darvill writes in his article, “no self-respecting farmer needs to be told to do these things — their skill and experience dictates how they work the land.”

Instead of organizing everyday activities, Darvill believes the Stonehenge calendar would have informed early farmers when to celebrate their harvest festivals, “or when to please the gods with their presence at key ceremonies.” While early farmers knew how to harvest, they required calendars to tell them when the summer and winter solstices would take place.

Calendars also provided a way for ancient leaders to solidify and legitimize power within their communities, with several studies indicating that this was the case. Darvill expresses the underlying logic: “Not only did elites control people and life on earth, but they also controlled the cosmos.”

Last but not least, time-reckoning systems helped civilizations conceptualize their cosmologies in an easily understandable and accessible manner. Just as some Hellenistic scholars posited the early Greek calendars coordinated interactions with the god Apollo, so too does Darvill speculate some elements of Stonehenge served as personifications of ancient deities.

Local versus external influences

Once Darvill collected enough evidence to argue that Stonehenge was, possibly, meant to function as a perpetual solar calendar, he was faced with another question: How did the society that built this enduring monument learn how to make such a calendar to begin with? There were two options: either they had figured it out themselves, or they had received help from far away.

“It is entirely possible,” Darvill states, “that communities living in north-western Europe during the late fourth and third millennia BC developed a solar calendar of the type suggested here on their own initiative.” Darvill points at passage graves in Newgrange, Ireland and Maes Howe, Orkney, which appear to align with celestial events during the winter solstice.

However, the sheer uniqueness of Stonehenge as an architectural and calendrical construction suggests that the builders were influenced by cultures that were geographically separated from their own. Darvill looks at the Eastern Mediterranean where, during the fourth millennium BC, cultures created lunar-stellar calendars that also reconciled the seasonal cycles of the sun.

In ancient Egypt, an increased interest in solar deities like the sun-god Ra kickstarted the development of a 365-day solar calendar. Like at Stonehenge, this calendar, also known as the Civil Calendar, comprises twelve months. Each month consists of 30 days, divided into three 10-day weeks, plus an intercalary month of five epagomenal days.

Though it would have been limited, there is evidence that contact between Northern European and Eastern Mediterranean and Egyptian cultures did occur. Darvill points to the Amesbury Archer, a body buried five kilometers southeast of Stonehenge. The grave, which dates back to around 2300 BC, contains several burial items, some of which have been traced back to continental Europe. What’s more, isotope analysis has revealed that the Archer himself was born in the Alps and did not come to Britain until he was a teenager.

The evidence does not stop there. Toby Wilkinson, an Egyptologist working at Fiji University, has documented Egypt’s export of stone vessels to distant places like Crete and, yes, Britain. Given that archaeologists found glass beads from Egypt less than three kilometers from Stonehenge, it is not unthinkable that the monument itself is of a partially foreign origin.