The “deep state” secret police is full of uneducated, incompetent underachievers

- The Venetian Inquisition and the Russian Oprichnina are among the earliest secret police organizations to resemble their modern counterparts in design and function.

- Though secret police officers are often depicted as intelligent, the reality is that they are made up of underperforming, poorly educated people who are easily turned into willing enforcers.

- The character and nature of secret police organizations is the same today as it was in the Middle Ages; what’s changed is the way they do their job.

Secret police organizations like Germany’s Geheime Staatspolizei (Gestapo) or the Soviet Union’s Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti (KGB) have played clearly identifiable roles in history. The history of these organizations themselves, however, remains mysterious.

It all started in Venice

The first state-run intelligence agency that resembled its modern-day counterparts in design and function seems to have been the Venetian Inquisition. It was managed by the Council of Ten, a governmental committee established in 1310 to investigate a plot to overthrow the city’s ruler, Doge Pietro Gradenigo.

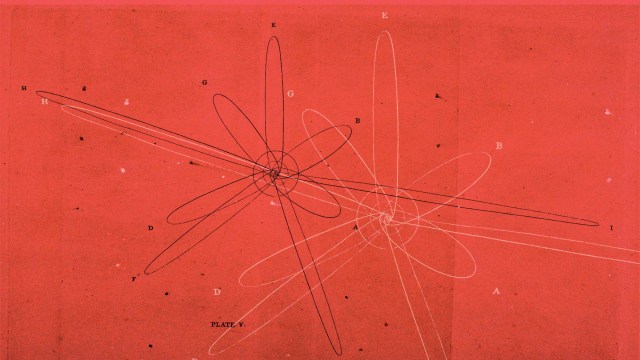

The Venetian Inquisition was larger and more centralized than any other espionage network in late medieval Europe. As the might of Venice grew, so did the responsibilities of the Inquisition. At first, members of the Council of Ten were tasked with protecting Venice itself. By the 15th century, they also kept an eye on Venetian dominions in northern Italy and the Levant — so much so that, when the Ottoman Empire invaded or the Portuguese tried to establish a new spice route, it was the Venetian Inquisition that formulated a plan of attack.

“Gradually,” Ioanna Iordanou writes in an article titled “The secret service of Renaissance Venice: intelligence organisation in the sixteenth century,” the Inquisition’s activities “encompassed all aspects of state security, including dealing with conspiracies, betrayals, and espionage.”

A state-within-a-state

Another contender for the first secret police organization is the Oprichnina of Imperial Russia. Compared to the Venetian Inquisition, the Oprichnina were small in size as well as in area of operation. They also stuck around for only a short time, being founded in 1565 and disbanded in 1572. But they were centralized, showing unquestioning loyalty to their creator: Ivan the Terrible.

The Oprichnina operated in a time when Russia was transitioning from a medieval society in which power was distributed among a collection of feudal lords to an empire ruled by one dynasty — Ivan’s — and several historians think the Oprichnina helped bring about this change.

His unparalleled (but by no means limitless) authority as the Grand Prince of Moscow was called into question by an exhaustive war with Poland and Lithuania. As a result, Ivan suspected other members of the Russian aristocracy — the boyars — were planning to betray him. The legend goes that when his leadership was needed most, he left the capital, set up camp at a royal hunting retreat, and informed the boyars that he only would return if they agreed to his hitherto rejected proposal to create the Oprichnina.

Described as a “private appanage, state-within-a-state” by Charles K. Halperin in “Contemporary Russian Perceptions of Ivan IV’s Oprichnina,” this organization of 1,000 members, eventually 6,000 strong, “became the instrument by which Ivan imposed mass terror on Muscovite society,” neutralizing the boyars through land confiscation and public executions.

Loyal but stupid

Secret service agents are often pictured in the media as highly capable individuals — think the multilingual SS officer Hans Landa from Quentin Tarantino’s film Inglourious Basterds. However, research suggests that most secret police organizations are staffed by people who are mediocre in skill and intellect.

Many members of Joseph Stalin’s NKVD — an organization that once arrested 1.5 million individuals in the span of just 16 months — were badly educated and performed unfavorably compared to other Soviet bureaucrats. Statistical analysis reveals that the same was true of Battalion 601, the central intelligence arm of the Argentine army tasked with identifying and arresting supporters of communist guerilla groups that tried to take over the country in the 1970s. Adam Scharpf and Christian Gläßel, authors of “Why Underachievers Dominate Secret Police Organizations: Evidence from Autocratic Argentina,” conclude that “officers who underperformed at the military academy were more likely to serve in the regime’s secret police unit.”

All this is somewhat strange. Secret police organizations are vital to the survival of authoritarian regimes, so why would their ranks be made up of incompetent people? The answer has to do with loyalty. Threatened with discharge and poor career prospects, underachievers are likely to join secret police organizations in search of future benefits — a situation their superiors are guaranteed to exploit. By providing employment to those who cannot find work elsewhere, Scharpf and Gläßel explain, authoritarians “produce willing enforcers and cement violent regimes.”

Another advantage of hiring uneducated, underperforming people is that they are less likely to think for themselves. They won’t question orders or conspire against their leaders, no matter how bleak things look for them. To make sure of this, secret police organizations control the lives and lifestyles of their employees in much the same way the regime exercises control over the general population.

This tradition traces back all the way to Ivan the Terrible, who handpicked his Oprichnina from the lower classes to ensure that they had no connection to the Russian aristocracy he was trying to uproot. Before being inducted into the organization, each member had to pledge allegiance to Ivan personally. They also promised, under threat of death, to stop associating with anyone who did not belong to the Oprichnina. Officers and their families were relocated to a separate part of Moscow, where they were completely isolated from the rest of society.

Secret police organizations in the 21st century

The essential character of secret police organizations is the same today as it was in the Middle Ages; it’s the way these organizations go about their job that’s changing. Digital surveillance technology is on the rise.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the People’s Republic of China. Since 1978, the year that Communist Party Chairman Deng Xiaoping announced a series of reforms turning the country’s planned economy into a mixed socialist market economy, the Chinese government has worked overtime to implement surveillance technology on an unprecedented scale. One big project was the so-called Great Firewall of China, which prevents internet users from accessing foreign websites.

When Xi Jinping assumed chairmanship of the CPC in 2013, the development of new surveillance technology started getting outsourced to private companies. On paper, these companies are supposed to publish reports detailing the products and services they provide to the government. In practice, records are distributed in such a way that makes them difficult to find and access.

Investigative work from the New York Times has brought the fruits of China’s socialist-capitalist partnerships into focus. Wi-Fi sniffers and IMSI-catchers can track people’s locations via their smartphones. It has been estimated that more than half of all the world’s surveillance cameras are located in China, where they are placed in busy areas to collect as much facial recognition data as possible. According to the investigators, this data is fed to analytical programs capable of identifying a person’s race and gender. Everything, which includes up to 2.5 billion facial images according to one estimate, is stored on state-owned servers. The goal of this video surveillance system, the investigators conclude, is “to achieve the ultimate goal of ‘controlling and managing people.’”

Centuries after the secret police were first invented, nothing has changed — but their new technological tools have made the job much easier for the underachievers who wield them.