The sapient paradox: With brains like ours, why did prehistoric humans wait millennia to start civilization?

- If modern human intelligence evolved 60,000 years ago, why did civilization not develop until 10,000 BC?

- This question lies at the heart of the sapient paradox, one of the great mysteries of human existence.

- Potential explanations range from a reconsideration of prehistory to the power of collective learning to early humans getting stuck in “gossip traps.”

The most significant developments in society and technology have all occurred over the past 10,000 years or so. That includes the agricultural, scientific, industrial, and digital revolutions, not to mention the dawn of religion, money, and any of the other symbolic concepts that separate Homo sapiens from other species.

We don’t know much about human activities beyond 10,000 years ago. But we do know that prehistoric people were genetically and intellectually equivalent to modern humans; research indicates that the level of intelligence required for history’s major societal and technological advancements evolved as early as 60,000 years ago when our ancestors began migrating out of Africa.

This begs the question: What took us so long? Why did humans spend 50,000 years (or more) in seemingly uneventful prehistory — with hunter-gatherers living the exact same way across thousands of generations — before starting on the trajectory that took us from cave paintings to (almost) self-driving cars in the comparative blink of an eye?

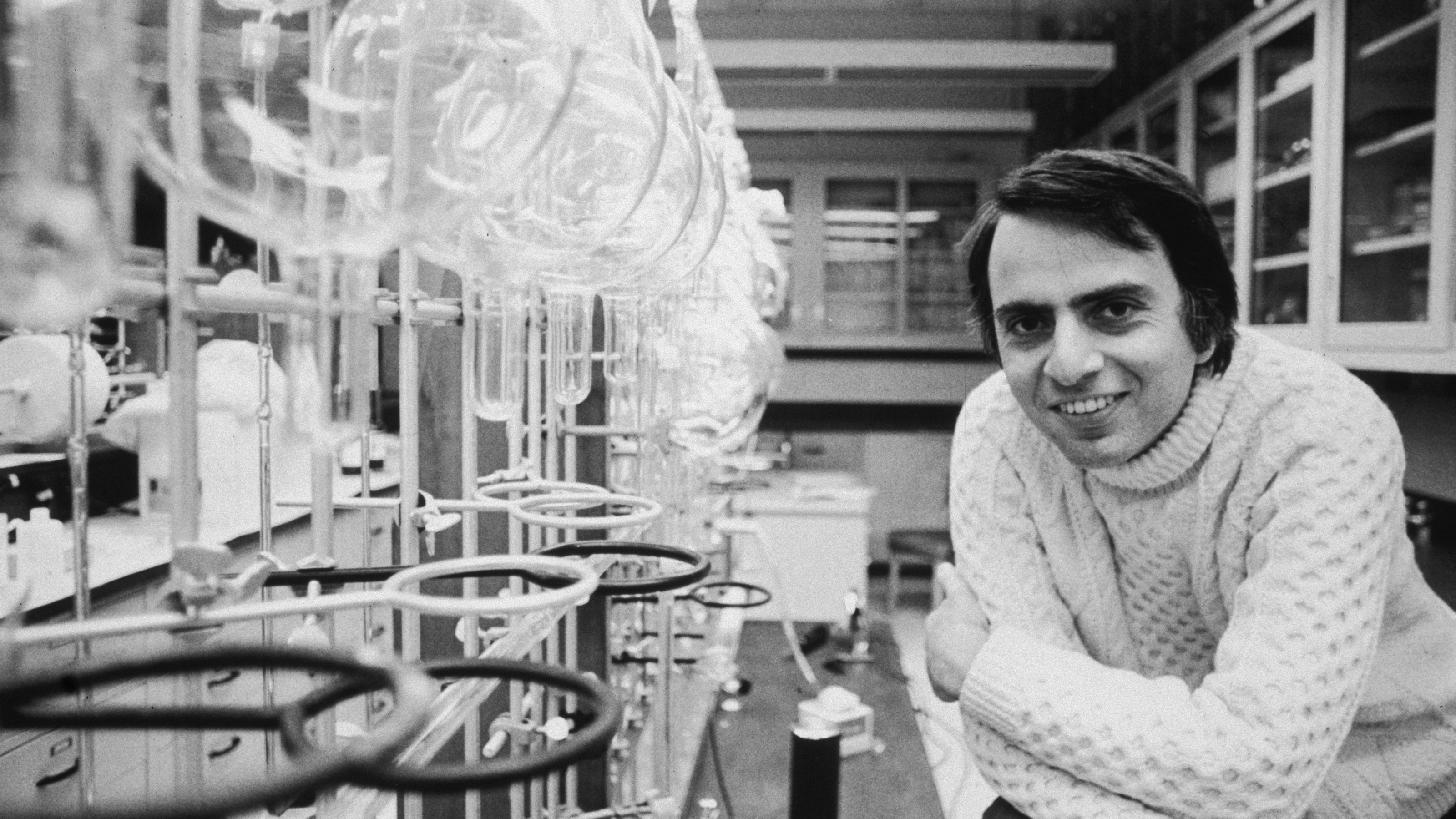

This question lies at the heart of the sapient paradox, a problem first formulated by the British archeologist and paleolinguist Colin Renfrew in a 1996 essay for Modeling the Human Mind titled, “The sapient behaviour paradox: how to test for potential?”

The sapient paradox has since cemented itself as one of the great unsolved mysteries of human existence. It stands alongside the Fermi paradox (named after Italian-American physicist Enrico Fermi), which asks why Earth appears to be the sole harbinger of life in our seemingly infinite Universe.

While there is no commonly accepted solution to the sapient paradox, several neuroscientists and archeologists have produced alluring hypotheses based on new discoveries related to ancient humans, as well as the brains that we inherited from them.

Preconceptions of prehistory

One possibility is that we haven’t given enough credit to examples of human development that took place in the distant past. Upon closer inspection, prehistory may not have been as uneventful or simplistic as it is often presented.

In their book The Dawn of Everything, anthropologist David Graeber and archeologist David Wengrow push back against the notion that hunter-gatherers lacked clearly defined social hierarchies, a notion that dates back to the Enlightenment-era rivalry between Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Instead, Graeber and Wengrow argue there is reason to believe that prehistoric social hierarchies were not only surprisingly complicated but also diverse, with some isolated pockets of people resorting to extreme egalitarianism while others organized themselves along the lines of chattel slavery.

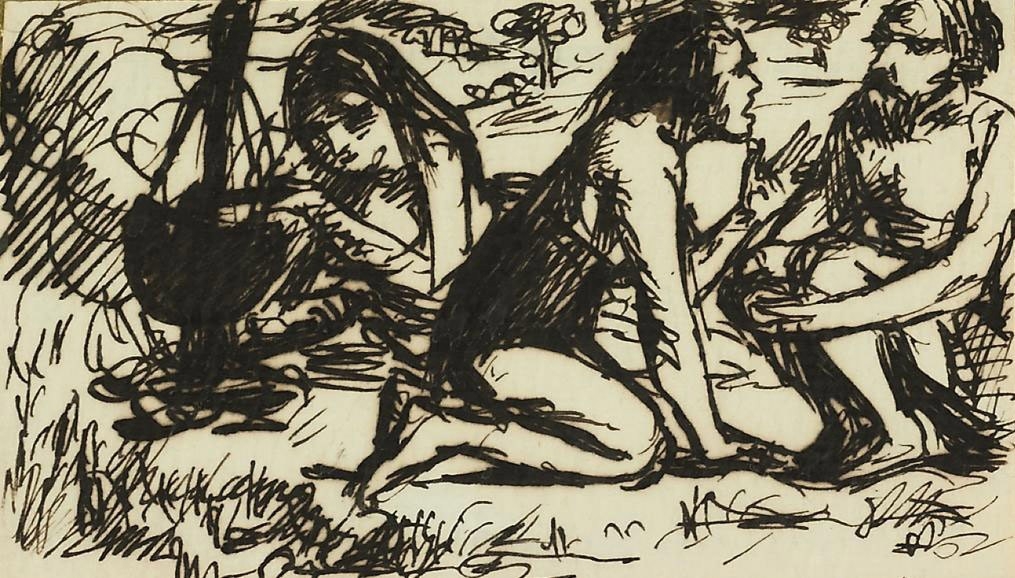

But that’s not all. Archeological studies have long suggested that complex speech and self-conscious reflection developed around 40,000 BC, which is also around the time Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis are thought to have coexisted in southwestern Europe.

These transitions were accompanied by a host of other new behaviors, including the refinement of stone tools from “flakes” to blades, the production of artifacts and personal adornments made from bones, antlers, and ivory, and the appearance of naturalistic art in modern-day France and Spain.

More recent discoveries suggest some of these behaviors occurred even earlier, in Africa. Evidence of symbolic expression in the form of intentional patterns of red ochre, found in Blombos Cave, near Cape Town, dates back to 70,000 BC, while some experts argue speech developed 200,000 years ago.

At a glance, the use of language and stone tools may not seem as impressive as the invention of, say, the steam engine or the internet. However, this could not be further from the truth, as the small steps taken by ancient humans allowed their modern-day descendants to run. When the oft-ignored developments of prehistoric times are given their due, the overall development of civilization starts to look more linear than exponential, making the sapient paradox less paradoxical.

Still, there’s another side to this coin — one concerning the nature of knowledge itself.

Dormant mechanisms

Although our genetic intelligence has changed little over the past 60,000 years, the way in which we apply that intelligence clearly has changed. The agricultural revolution, which took place between 12,000 and 9,000 BC, after the end of the last ice age, played a crucial — and even catalytic — role in that transformation.

Before agriculture, it was difficult for hunter-gatherers to preserve the knowledge they accumulated over the course of their individual lives. Because they lived in small groups, often got killed while hunting, and had little contact with other tribes, information rarely spread to another tribe or generation.

David Christian, a scholar of Big History, has referred to modern-day primates as an analogy. When a skilled hunter in a troop of baboons dies, his hunting techniques are not passed down after his death. As a result, the troop — and, by extension, the species — does not expand.

In retrospect, the agricultural revolution matters not only because it allowed humans to live in larger groups, live longer, and establish sustained contact with other communities, but also because all of these things made it easier for us to preserve and transmit knowledge.

In their work, scholars like Christian refer to the ability to preserve and transmit knowledge as collective learning. In addition to being the key to solving the sapient paradox, it may well be the overarching theme of human history in general.

Christian certainly seems to think so. As does Renfrew, who in one of his many essays on the subject writes that, because civilization emerged long after the biological basis for intelligence, emphasis must be placed on “the aspects of the socialization process of shared experience.”

The centrality of the agricultural revolution is reflected in the archeological record, which shows that monetary systems and organized religion — two cornerstones of society — did not come into existence on any large scale until after ancient humans began farming.

It’s worth noting the link between population density and human development stretches back into prehistoric times as well, with the same record showing that Homo ergaster toolmaking improved in quality and variety in periods when early humans lived closest together, but stagnated when they spread out.

Renfrew, for his part, concludes that the agricultural revolution — which would usher in the first large-scale societies — must have activated “special mechanisms” of intelligence and behavior whose potential, though “inherent in the genome,” had hitherto laid dormant.

The gossip trap

Scholars are constantly coming up with new ways of looking at the sapient paradox. One original perspective was recently outlined by American neuroscientist Erik Hoel in his prize-winning essay The gossip trap, itself a review of Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything.

In his essay, Hoel also questions assumptions about the distant past. The discovery of prehistoric developments like the creation of beads and cave art, he argues, does not solve the sapient paradox, but only makes subsequent developments more perplexing. He also doubts the agricultural revolution was delayed by the last ice age, as early farmers worked in extreme environmental conditions.

For his own solution to the sapient paradox, Hoel turns to the aforementioned comparisons with the Fermi paradox. Since the latter is often explained by the existence of a “Great Filter” — i.e. if aliens exist, they will not contact us until humanity becomes more advanced — the former may have something to do with a “Great Trap” that kept civilization from escaping prehistory.

As implied by the title of his essay, Hoel identifies this trap as humanity’s propensity for gossip, which would have played an important role in small hunter-gatherer tribes where everyone knew each other personally. In anthropological literature, gossip is described as a “leveling mechanism” that prevents individuals from obtaining too much power.

Demonstrations of this mechanism can be found in prehistory, when, according to Graeber and Wengrow, “talented hunters [were] systemically mocked and belittled,” as well as in modern times, when, in an example cited by Hoel, well-to-do Haitian peasants will buy several smaller fields instead of one large plot of land so as not to antagonize their peers.

Once people started living in larger groups, informal relationships based on gossip and popularity made way for formal institutions whose authority is not merely vested in their social reputation. Civilization, Hoel concludes, is really “a superstructure that levels leveling mechanisms, freeing us from the gossip trap.”

However, Hoel suggests that social media might be pulling us back into the gossip trap. The basic idea is that social media is resurrecting “our innate form of government,” which is raw social power. Social media is able to do this because it facilitates the transmission of gossip like no other technology has before, enabling virtually anyone to gossip about anyone else. This echoes the nature of humanity’s small-group beginnings.

“One obvious sign you’re living in a gossip trap is when the primary mode of dispute resolution becomes social pressure,” he writes in his essay. “And almost everywhere you look lately, it’s like social media is wearing a skin suit made of our laws, institutions, and governments. Does it not feel, just in the past decade, as if raw social power has outstripped anything resembling formal power?”

He adds later: “…with the advent of social media, and the resultant triumph of the spread of gossip over Dunbar’s number, we might have just inadvertently performed the equivalent of summoning an Elder God.”

Alongside collective learning and its relationship to the agricultural revolution, the gossip trap provides yet another piece to the puzzle of the sapient paradox.