Scientists pretend to be Neanderthals to catch birds

- Neanderthals are often misunderstood to be dimwitted and brutish cavemen who went extinct for lack of intelligence.

- However, evidence shows that they made complex tools, had basic medicine, cared for their vulnerable, and even performed burial rites.

- In a new paper, Spanish researchers experimented with various methods of catching crows during nighttime with bare hands to study how and where Neanderthals might have done the same.

Imagine you are transported back in time 200,000 years ago to live among Neanderthals. Assuming you are not instantly killed for your strange looks and clothing, do you think you could live and function alongside our closest ancient relatives?

To succeed, you would need not only cunning and bravery, but also a pair of quick hands.

That’s one of the key takeaways of a study recently published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. The results suggest that Neanderthals were agile experts at catching birds at night, a finding that builds upon a growing body of research showing how Neanderthals were far more socially and cognitively intelligent than previously thought.

Tricks of the trade

In many ways, Neanderthals demonstrated behaviors and social patterns that were similar to our Homo sapien ancestors. For example, archaeological evidence shows that Neanderthals developed rudimentary medicine: Tooth and jaw fossils have been found packed with painkilling plants, like poplar. Bones have been found knitted together and healed, suggesting communities had basic medical skills, not to mention a sense of compassion.

At multiple sites, such as La Chapelle-aux-Saints, researchers have discovered the remains of toothless, infirm, elderly Neanderthals who were years, or decades, past being able to care for themselves. This implies that these prehistoric communities had some sense of duty, care, or honor that belies the idea that Neanderthals were mere stone-bashing idiots.

Neanderthals also seemed to perform certain burial rites, pointing towards quasi-religious beliefs. At the very least, Neanderthals buried their dead when they didn’t need to, and in some cases they left behind displays and offerings of flowers (although it’s possible those were the work of burrowing rodents).

Tooled up

Impressive, sure. But we are still dealing with a primitive species — barely a step up from large primates, right? Well, not only does that slightly undersell our primate friends, but Neanderthals were far more technologically advanced than commonly thought.

Neanderthals made and used fairly sophisticated tools. They could twist together three strands of tree fibers to make a basic string. They could make spear points, knives, harpoons, engraving instruments, skinning tools, and hammers. Sure, it’s not quite nuclear fusion, but it’s far more than any other non-human primate can do, and it’s similar to what Homo sapiens were capable of when they existed contemporaneously with Neanderthals.

What’s more, Neanderthals were strategic. Many successful predator species have evolved the abilities needed to hunt as a group — they have the social awareness and teamwork required to track, attack, kill, and eat large prey. Neanderthals were no different: Archaeological evidence suggests they worked together to take down large animals.

However, paleoecological research suggests that hunting large game probably would have been an uncommon occurrence for Neanderthals. Large animals, after all, would have been fairly hard to come by, and hunting them was physically demanding and dangerous. The recent study suggests Neanderthals might have spent more time honing a different but equally impressive hunting skill: catching birds in the dark with their bare hands.

Just winging it

The researchers behind the recent study noticed there was a disproportionately large amount of bird remains found in sites where Neanderthal fossils were also discovered. One particular bird species is especially likely to be found near Neanderthal remains: the chough, a type of crow that’s common in Eurasia and was within “easy access of Neanderthals”.

But how, exactly, did the early hominins capture and kill these cave birds? Finding out required some testing. The team hypothesized that it would be easiest to catch choughs at night while the birds were roosting. To find out, the researchers tried it themselves.

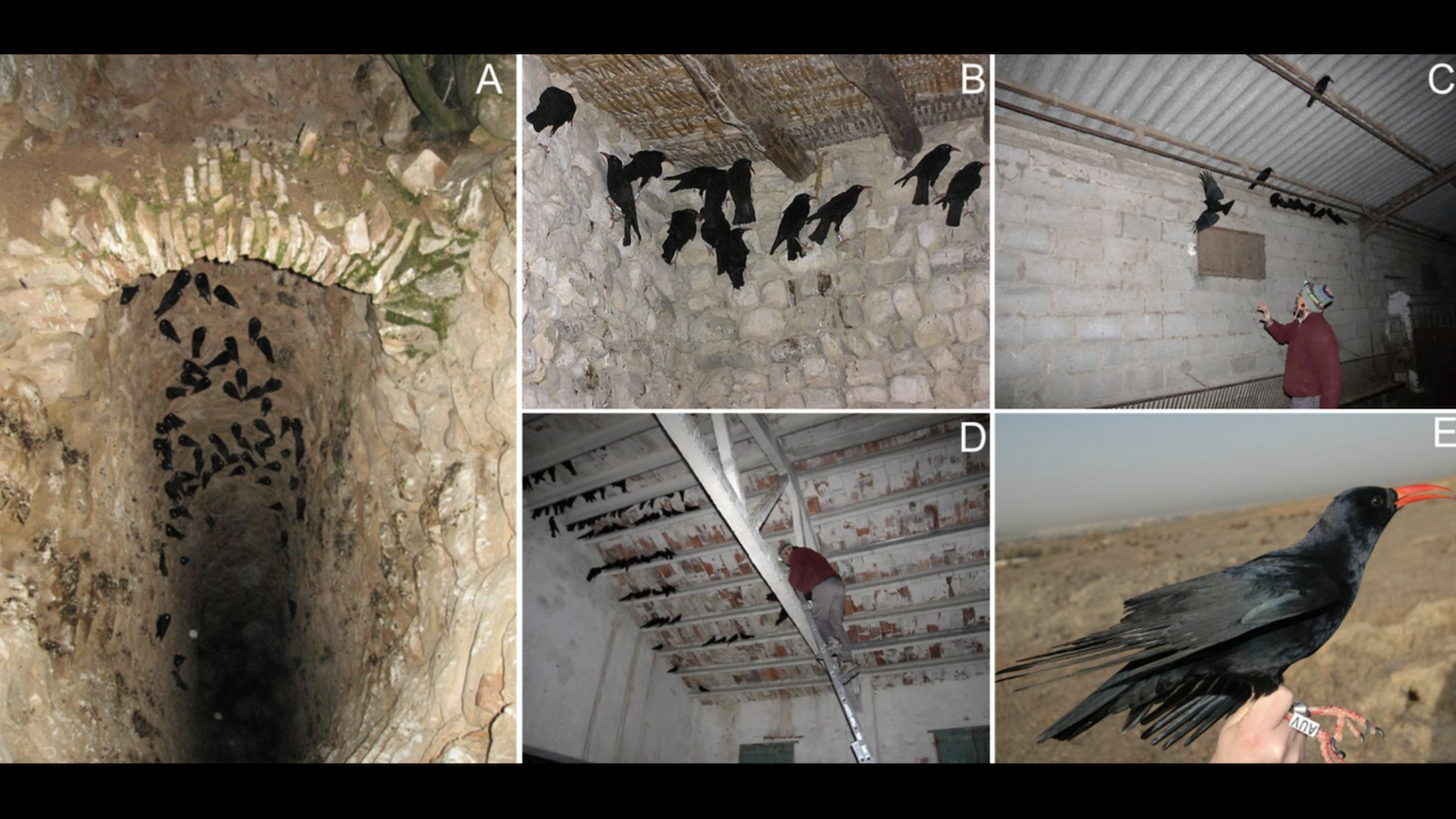

Like any good bank heist, they scouted out chough behavior during the night to examine how the birds dealt with nocturnal predators. Then the researchers experimented with a variety of different bird-catching techniques to determine which approach worked best. For example, they varied up the team size, tried different tools, and changed up how they entered the roosting sites (which were located in places like caves, tunnels, and quarries). The researchers measured the efficacy of each approach and recorded how the birds reacted.

The results showed that the most effective strategy was to have a four- to five-person team enter the roosting site through a “silent night-time approach,” dazzle the birds with a bright lights, and corner them in “vertical cavities like wells” where they could be easily netted or handled. Some of the researchers became skilled bird-catchers; the study noted that on many occasions “the dazzled choughs were captured by bare hand in flight.” In the name of science, these paleoecologists were displaying superhero-like powers in an attempt to mimic Neanderthal behavior.

Don’t bad mouth a Neanderthal

The unconventional study highlights the growing body of research that shows Neanderthals were not unintelligent half-beasts who succumbed to the intellect and reason of brilliant Homo sapiens. Instead, Neanderthals made and used sophisticated tools, cared for their vulnerable, and demonstrated basic burial rituals.

The recent research suggests they also spent a lot of time raiding caves full of crows — creeping in at night, wafting about flaming torches, and catching the dazzled birds midflight. It makes me happy to think that a team of 21st-century scientists managed to recreate the ancient craft.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.