Lost Cities, Ancient Tombs: The cemetery of the golden chiefs

- In a grassy, sun-parched field in central Panama, gold was coming out of the ground.

- Archaeologist Julia Mayo and her team had uncovered the rich burials of great chiefs that belonged to a still unnamed culture.

- This site helps build the case for the existence of complex pre-Hispanic cultures in the forests of Central America and northern South America.

The following is excerpted from Lost Cities, Ancient Tombs, to be published by National Geographic Books on November 2. It is reprinted courtesy of National Geographic Books.

Part of the lure of archaeology is the unknown, the feeling that anything’s possible. But while archaeologists seek to answer questions scientifically, they’re not immune to the wonder of big discoveries. They might hypothesize that a field dotted with monoliths may hold the graves of warrior-chiefs, but are nevertheless awestruck when shovels and trowels suddenly reveal skeletons covered in gold accessories. The ruins of cities and settlements, rich in artifacts, can be just as stunning as the luxury-filled graves of elites — especially when new evidence overturns earlier notions of what we held true. But no matter how much evidence is unearthed, puzzles still cry out to the curious, enticing them to continue excavating, sifting through the clues, and searching for a meaning.

Panama, AD 700-1000

In a grassy, sun-parched field in central Panama, gold was coming out of the ground so fast that archaeologist Julia Mayo was tempted to yell, “Stop, stop!” For years she had been working for this moment, waiting for it. But now she was overwhelmed.

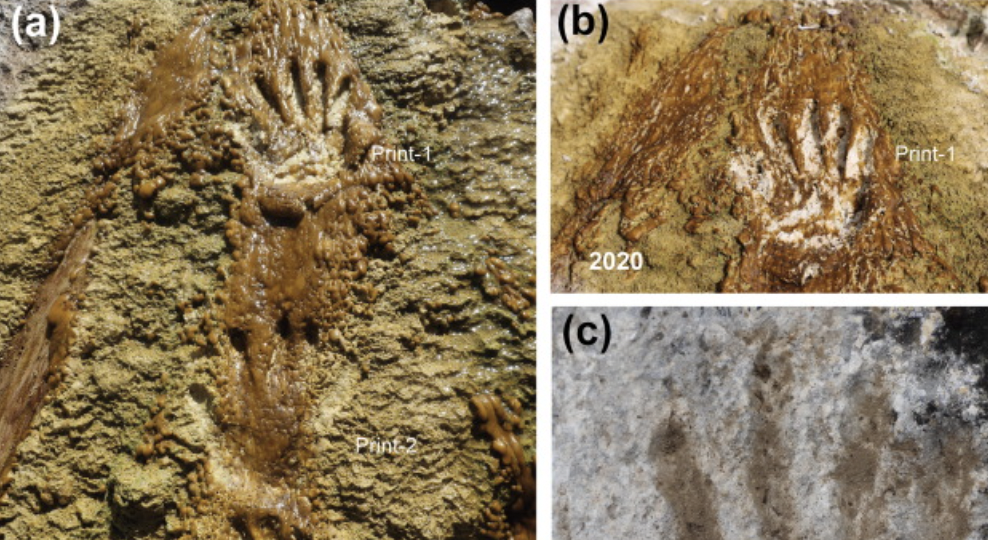

Determined to uncover new evidence of the ancient society she had been studying since graduate school, Mayo and her team began geophysical surveys in 2005 at a site known as El Caño, named for a waterfall on one of the area’s many rivers. The results identified a circle of long-forgotten graves. By 2010 Mayo and her team had dug a pit 16 feet deep and discovered the remains of a warrior-chieftain bedecked in gold — two embossed breastplates, four arm cuffs, a bracelet of bells, a belt of hollow gold beads as plump as olives, more than 2,000 tiny spheres arranged as if once sewn to a sash, and hundreds of tubular beads tracing a zigzag pattern on a lower leg. That alone would have been the find of a lifetime. But it was just the beginning. The archaeologists returned the following year during the January-to-April dry season and unearthed a second burial every bit as rich as the first. Bearing two gold breastplates in front, two in back, four arm cuffs, and a luminous emerald, the deceased was surely another supreme chief. Beneath him stretched a layer of tangled human skeletons — possibly sacrificed war captives. Radiocarbon tests would date the burial to about AD 900.

In field seasons through the spring of 2017, Mayo and her team uncovered the rich burials of great chiefs that belonged to a still unnamed culture and that date from about the eighth to the tenth centuries. Living in small, belligerent communities vying for control of the savannas, forests, rivers, and coastal waters, the chiefs covered themselves in gold to proclaim their rank. Tantalizing hints that fathers bequeathed wealth and power to their sons continued to turn up until finally, in 2013, Mayo found proof: the remains of a 12-year-old male wearing gold arm cuffs inscribed with images of the culture’s crocodile god. Close by lay the remains of a chief who wore gold breastplates, beads, bells, mysterious figurines in fantastical shapes, and arm cuffs also inscribed with images of the crocodile god.

Mayo is convinced that the pair attests to inherited power. This theory has great implications for El Caño. “One of the characteristics of complex chiefdoms is that social status is passed down from father to son,” she explained. That means this cemetery represents a society that was much more sophisticated than previously believed.

It also means that this site helps build the case for the existence of complex pre-Hispanic cultures in the forests of Central America and northern South America. Most of their material culture has rotted away in the heat and humidity — houses of wood and wattle, roofs of thatch, baskets, mats, animal skins, feathers — leaving mainly broken pottery and stone tools. But in this place, at least, people worked gold and other luxury materials with great skill — and the shimmer of the surviving treasures endures as a testament to the culture’s centuries of prosperity and accomplishment.

The preceding was excerpted from Lost Cities, Ancient Tombs, to be published by National Geographic Books on November 2. It is reprinted courtesy of National Geographic Books.