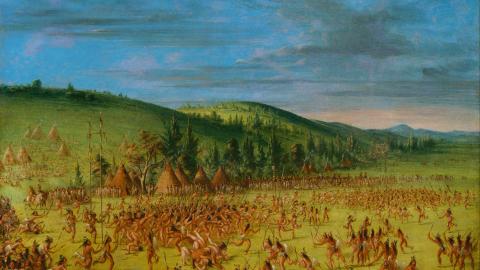

The little brother of war: The history of lacrosse

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

Lacrosse, North America’s oldest sport, goes far beyond the contemporary idea of a team sport.

For the Iroquois, it was a type of military training, and a way to honor the gods.

Long, long ago, only the quadrupeds played lacrosse, against the birds. The leaders of the first team were the bear, the deer and the turtle; of the second, the owl, the hawk and the eagle. One time, not long after a match, the mouse and the squirrel visited the birds and asked whether they could join their team.

“Why don’t you ask the quadrupeds?” the eagle asked.

“We did. They laughed at us because we’re small,” the mouse and the squirrel replied.

After long deliberations, the birds decided to accept the players, but they had to be equipped with wings. One of the birds suggested finding a drum, taking off the skin and attaching it to the mouse’s legs. And thus was born the bat. Wanting to test their new player, they threw the ball up. It turned out that the bat could keep it in the air, with great control. The owl, hawk and eagle decided that the new player would strengthen their team. There was no skin left for the squirrel, and no time to find another drum, as the match was about to start.

“And maybe we could stretch the squirrel’s skin?” the owl suggested.

And the birds pulled with all their might, from every direction, until they made the flying squirrel.

The bear and the eagle started the match. The flying squirrel got the ball and passed to the hawk, who kept it in the air for a while, but made an error in the end, and it was almost stolen by the deer. At the last moment, the eagle took the ball. He faked a pass to the flying squirrel, but in the end passed the ball to the bat, who scored the winning goal.

This legend (in slightly varying versions) has been told for centuries by the Indigenous peoples of North America. The moral of the story is that regardless of size and strength, one day anybody can come in handy.

Sticks like crosiers

We don’t know what exactly the French Jesuit Jean de Brébeuf saw when in 1637 he travelled through what is now the Canadian province of Ontario. He saw people behaving strangely – neither fighting nor playing. His attention was drawn to the sticks they held. They reminded him of a bishop’s crosier – in French, a crosse. That’s the name De Brébeuf gave to this activity, unknown in Europe. But he didn’t devote a great deal of space to it in his memoirs. There was no information on the rules, the number of players or gameplay. It’s possible that the reason was simply the missionary’s approach to foreign games – he treated them with contempt, and believed them to be anti-Christian. Additionally, the games were an occasion for increased alcohol consumption, and gambling for horses, weapons and clothes; it even happened that the losers were left with nothing at all.

Another source of doubt concerning De Brébeuf’s discovery is that the Indigenous North Americans played many games in which a ball and stick were important; they differed only in the details. The Cherokee played to 12 points; the Menominee to four; the Great Lakes tribes to three; and the Iroquois required different scores depending on the circumstances and the stakes. Usually the matches happened on land between villages, and lasted from sunrise to sunset (though there were also multi-day games). The pitch could be several kilometres long, and the goals hundreds of metres wide. Sometimes as many as 1000 people took part. The goal of the players equipped with sticks was to put into the net a ball made from wood, clay or deer skin. The detailed rules were set by the elders the day before each match.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

Power of muscles, power of ritual

The Shawnee let women play, but only with their hands. Only the men used sticks. The Dakota didn’t have any such prohibitions. They even allowed mixed matches, but for each male player there had to be five females (the women also competed among themselves). But these were exceptions; in most tribes, women were prohibited from coming near the pitch. Men whose wives were pregnant weren’t considered for the team, as it was believed that they had transferred all their strength to the child and were greatly weakened. For three days before the match, the players were required to refrain from sex. Before the team left the village, the shamans sent scouts to make sure the way was clear – enemies could leave something along the path that would weaken the players.

Before the match began, the players marked their bodies with charcoal; they believed this gave them strength. In clouds of sacred tobacco thrown onto a fire, they asked for supernatural strength to give them the eyesight of the hawk, the agility of the deer, the strength of the bear. But the most important were the sticks. The players paid them the same respect as they did to weapons. Before entering the pitch they smeared them with magical ointments, festooning them with amulets prepared by the shamans. The sticks were also placed in players’ coffins so that they’d have equipment to play with in the afterlife. The reasons for playing a match were legion. It could be about maintaining relations with neighbours (after a game ended, a rematch was immediately agreed); rendering honour to the heavens, e.g. on behalf of an ill person (whose fate depended on the result); commemorating the dead. Matches could also be part of a funerary rite.

Lacrosse was also used to solve conflicts; the game was seen as a great method of keeping warriors in shape. Sometimes, during a match, the players stopped worrying about the ball and focused on each other. Confrontations switched instantly into wrestling or fistfights. Hence the Mohawk-speaking tribes called their version of lacrosse begadwe, or the ‘little brother of war’, and those who spoke Onondaga, dehuntshigwa’es: ‘small war’.

The most spectacular example of using lacrosse during a battle was a manoeuvre by Ojibwa chief Minweweh in 1763. At that time, several tribes rose up against British rule, starting what became known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. Since the springtime, the Sauks and Ojibwas had been passing through the Mackinac straits to Fort Michilimackinac, one of the strongest fortresses in the region, and one of the most difficult to capture. On 2nd June, unexpectedly for the British, a lacrosse match began. The tribes played outside the fort for several hours, when suddenly the play turned into an attack, and the players into warriors. The fort fell; 35 British soldiers perished. The capture of Michilimackinac turned out to be one of the most effective victories of the rebellion; the Europeans retook the fort only a year later.

Ball and identity

Men’s teams have 10 players; women’s have 12. The men play four quarters; the women, two halves. The men wear helmets and gloves, while the women have protective goggles. All of them carry sticks with a pouch-like net on the end. The object is to put the ball (slightly larger than a golf ball) into a square goal. That’s how lacrosse looks today.

In 1860, the Montreal dentist William George Beers recorded the rules on paper for the first time. Since then, of course, many things have changed, but lacrosse has proven resistant to the disease of modernity. It hasn’t been corrupted by money, as there’s never been any. The best players are semi-pros, earning about $30,000 a year in America’s Major League Lacrosse. Not a small amount, but compared to the millions that basketball, soccer, baseball and American football players cart off the field, it’s nothing.

The presence of an Iroquois team at the world championships shows how lacrosse hasn’t completely lost its character or its consciousness of its roots. The team can’t compete in the Olympics or the World Cup (not that they have particularly tried); those events are only for nations with their own territory, recognized by the international community. The lacrosse world championships are different. It’s the only event where the Iroquois can send a team, sing their anthem, show their colours. For them, this is probably even more important than sporting success measured by scores and medals (over three decades, they’ve only taken home two bronzes).

In 2010, the world championships were organized in Manchester in the UK. Right before they started, the British government announced that it wouldn’t let players enter the country on their Iroquois passports (which the Confederation has been issuing for almost 100 years). When the team got stuck in New York, then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton proposed express issuance of American documents for the players; with US passports, they wouldn’t have any problems at the border. The Iroquois deemed the idea an attack on their identity. They preferred to withdraw from the championship rather than taking part with passports from another state.

Translated from the Polish by Nathaniel Espino.

Reprinted with permission of Przekrój. Read the original article.