Human migration: North America settled as early as 26,000 years ago

- While human migration from Africa into Eurasia is well-documented, when and how we arrived in North America is not.

- Now, fossilized footsteps unearthed in New Mexico suggest humans were present on the continent during the Last Glacial Maximum.

- Because glaciers would have rendered North America inaccessible at the time, the researchers suggest humans may have arrived here much earlier.

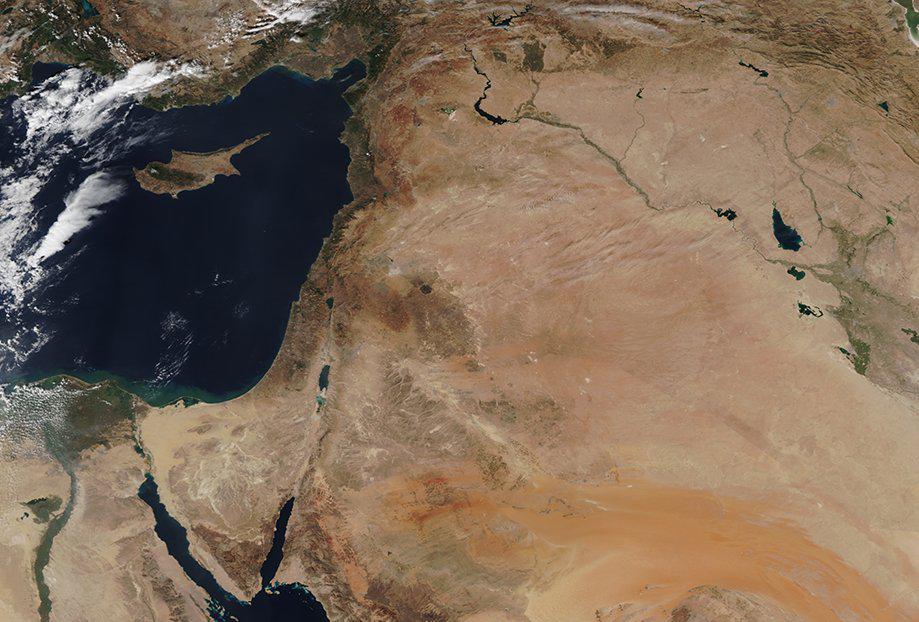

Human migration into North America marks the final step in our species’ journey out of its place of origin in Africa. Unlike the passage into Eurasia — which is well-documented thanks to fossils preserved in the Levant region on the eastern banks of the Mediterranean — our arrival into North America remains, to a large extent, shrouded in mystery.

Some paleontologists point to the so-called Clovis tribes — which settled near the eponymous town in today’s New Mexico around 13 thousand years ago and were known for the pointy ivory tools they left behind — as the earliest evidence of human occupation on the continent. Others, however, claim to have found traces that go back as far as 26 thousand years ago.

This period is also known as the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), a time when most of North America was covered in thick sheets of polar ice, and the only migratory routes our ancestors are known to have taken on their way onto the continent — the Ice-Free Corridor and the Pacific Coastal Route — probably would have been frozen over.

The idea that humans somehow could have managed to get to America in such an extreme climate seems unlikely. So unlikely, in fact, that the archaeologists who recently uncovered new evidence of humans in North America during the LGM were left with one conclusion: our ancestors must have made it to the continent before the ice sheets had been formed.

Tracing the footsteps of human migration

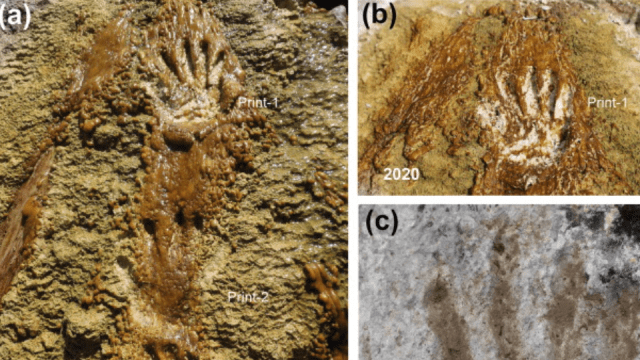

The evidence in question concerns a collection of human footprints in White Sands National Park in New Mexico, nearly 300 miles southwest of Clovis. Using reliable measurement tools, researchers report in the journal Science that they dated the footsteps to around 23,000 years, offering what they say is “definitive evidence of human occupation of North America south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the LGM.”

While the regions our ancestors must have passed to get to White Sands would have been dangerous and inhospitable, the place they ultimately chose to settle was not. Ancient layers of sediment reveal that the park sits on top of a 14,000-square-mile basin that once encompassed an ecosystem of wetlands filled with Pleistocene flora and fauna around Lake Otero.

The inside of the basin, it turns out, is covered with footsteps — not just from humans, but canines, too. Footsteps of proboscideans — a branch of the afrotherian family tree that includes elephants and mammoths — were also found. All in all, the researchers collected as many as 61 distinct footprints from the site at White Sands.

Many of the footprints had been exquisitely preserved, complete with heel impressions, longitudinal arches, and toe pads. Consequently, researchers were able to compare the footprints of these original American settlers with both the footprints of modern-day humans and index fossils that were collected in Namibia.

Piecing the past back together

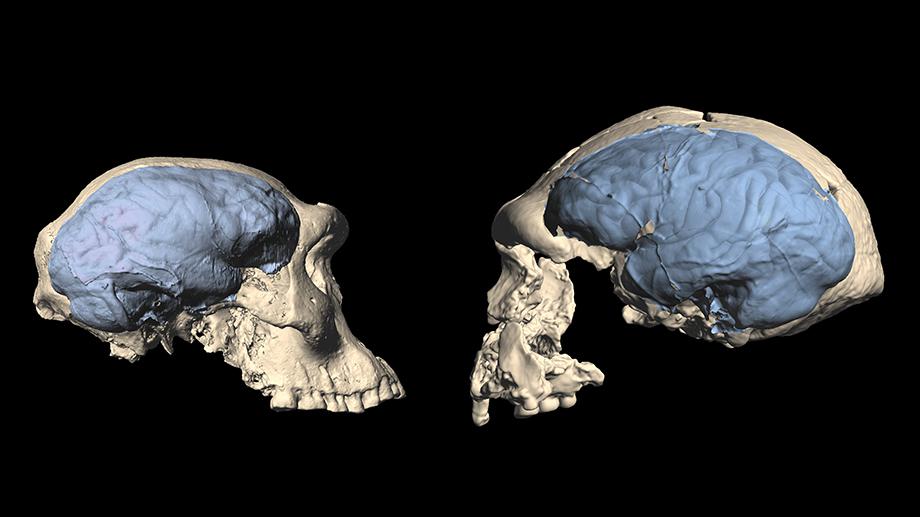

The differences and similarities between each print tell us a number of things. For starters, similarities across the board tell us that we are dealing with members from our own lineage, not some other hominin species. Like the Namibian prints and unlike ours, the American ones are flat, indicating our ancestors did not yet sport footwear when they came to the continent.

The same goes for the placement of each footprint. At the digging site, researchers quickly noticed that many if not all of the trails they had uncovered were noticeably smaller than the other tracks. The researchers suggest this could be the result of a common prehistoric “division of labor,” one where adults remained stationary while children carried and fetched things for them.

Last but not least, the irrefutable presence of humans in this area during this time period allows us to get a clearer picture of what the climate and ecology of that time might have looked like. The fossils found at White Sands, for instance, tell us that the North American climate during the LGM must have been forgiving enough to allow humans to survive.

To a certain extent, it probably was. Around the time these footprints were made, the Earth was slowly starting to warm again while the glaciers were getting ready to melt away. According to the researchers, a series of dry spells must have lowered the water levels of Lake Otero to allow human and megafauna populations to briefly flourish.

An unknown road

Meanwhile, the Ice-Free Corridor and the Pacific Coastal Route remained frozen, leaving the researchers to propose that their fossils prove our human ancestors must have settled in America much earlier than we originally thought, early enough for them to have traveled into the continent before the LGM rendered their only points of entry inaccessible.

The fossils have led them to other conclusions, too. They show, for one, that humans were able to live alongside megafauna for as long as two millennia before hunting many species to extinction. Considering that relationships between early humans and megafauna remain poorly understood, this is no small discovery.

In the end, though, the White Sands fossils raise more questions about human migration than they answer. “Exactly when people first arrived in the Western Hemisphere and when continuous occupation was established are still uncertain and contested,” the researchers conclude. “What we present here is evidence of a firm time and location when humans were present in North America.”