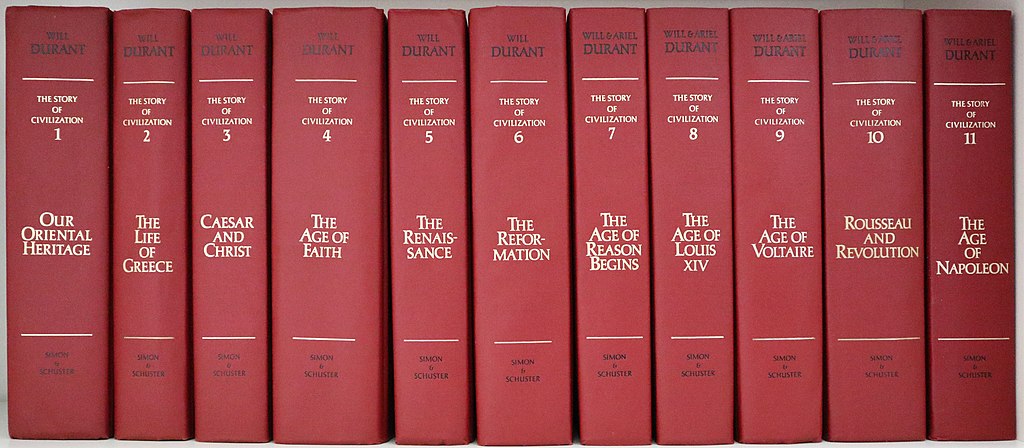

Together, Will and Ariel Durant wrote more than 53 surveys on human existence. Many of these, including The Story of Philosophy and the eleven-volume series The Story of Civilization, became national bestsellers. The latter garnered the couple a Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction as well as a Presidential Medal of Freedom, which they received from Gerald Ford.

As academics, the Durants were renowned both for the breadth of their knowledge and the digestibility of their writing style. Tracing the evolution of concepts like morality, religion, and war across centuries and throughout different societies, the husband and wife team wrote in a manner that was captivating and easy to understand — even for people who never studied at the college level.

This interest in writing for the “common man” as opposed to other scholars stemmed from their upbringing: Will grew up in a large family of French-Canadian Catholics whose patriarch was an illiterate factory worker; Ariel was born in a Jewish ghetto in the Ukraine and arrived in the U.S. with nothing but the clothes on her back.

The Durants were, for the most part, fiercely independent thinkers. During a time when people’s impression of reality was heavily influenced by social, political, and economic movements like capitalism, fascism, and communism, Will and Ariel attempted to survey history in its totality. Along the way, they came closer to writing an unbiased history of civilization than any academic before or after.

The view of the whole

Though the Durants are typically referred to as historians, they were in fact much more than that. Their writing not only outlines the history of past events but also attempts to understand their manifold causes and consequences. In any given essay or text, readers are treated to lectures in philosophy, religion, economics, science, and the arts.

The biggest of big picture thinkers, the Durants perceived so many connections between academic disciplines that they saw little to no use in separating them. The couple treated philosophy not as the pursuit of knowledge or the means by which that knowledge is attained but the study of reality — a subject which, so they thought, ought to be studied in its entirety.

“By and large, human nature does not change in the historic period. The meaning of history is it is man laid bare. The present is the past rolled up for action. The past is the present unrolled for understanding.”

Will and Ariel Durant, The Lessons of History

In one of his essays, Will Durant defined wisdom as “total perspective — seeing an object, event, or idea in all its pertinent relationships.” The term he used for this, sub specie totius or “view of the whole,” was itself adopted from Baruch Spinoza’s maxim, sub specie eternitatis, which placed intellectual emphasis on eternity or timelessness instead.

In the opening of their 1968 book, The Lessons of History — itself a condensation of and commentary on The Story of Civilization — the Durants reiterated yet again that their aim had never been originality but inclusiveness: to identify the significance of past events and figure out how they weave together into the grand and infinitely complex tapestry of human history.

The historian as lover

Where lesser academics often fall prey to egotism, the Durants remained humble in spite of their success. To them, the true philosopher was not a “possessor” of wisdom so much as a “lover” of it. “We can only seek wisdom devotedly,” wrote Will Durant in the aforementioned essay, “like a lover fated, as on Keats’ Grecian urn, never to possess but only to desire.”

Their inquisitive attitude was similar to that of Socrates, a thinker who — at least in the very first dialogues which Plato devoted to him — was more interested in questioning the premises of his contemporaries than proposing any ideas of his own. Socrates also likened philosophy to a beautiful man or woman, and he fancied himself their greatest and most subservient admirer.

To render their analyses as objectively as possible, the Durants took great pains to remove themselves from the equation. Will, for his part, is often commemorated as the “gentle philosopher.” He wrote and studied not to find justifications for his personal beliefs but out of a genuine interest in the world around him. As a result, his work combines a mature sense of reservation with childlike wonder.

In a sympathetic retrospective on the Durants and their career, the conservative columnist Daniel J. Flynn pinpointed this lack of personal aspiration as the thing that separated Will and Ariel from their colleagues. “The Durants’ style of cutting to the point,” he wrote in the National Review, “made them anathema to academics who saw clarity as a vice. Their critics wrote to be cited; the Durants wrote to be read.”

The perils of macrohistory

In spite of their “inclusiveness,” the Durants remain sympathetic to the great man theory, a compelling but outdated method of historical analysis that interprets past events as having been disproportionally dependent on the actions and ideas of noteworthy individuals. “The real history of man,” wrote the couple in The Story of Civilization, “is in the lasting contributions made by geniuses.”

The Durants grew up at the start of the 20th century, a period of unparalleled positivism when faith in the great man theory was still growing strong. This faith was eventually shattered by the catastrophes that were the First and Second World War, after which it was further questioned by scholars, who noted the accomplishments of these “great men” could not be considered a product of their genius alone.

“History repeats itself, but only in outline and in the large. We may reasonably expect that in the future, as in the past, some new states will rise, some old states will subside; that new civilizations will begin with pasture and agriculture, expand into commerce and industry, and luxuriate with finance; that thought will pass from supernatural to legendary to naturalistic explanations; that new theories, inventions, discoveries, and errors will agitate the intellectual currents; that new generations will rebel against the old and pass from rebellion to conformity and reaction; that experiments in morals will loosen tradition and frighten its beneficiaries; and that the excitement of innovation will be forgotten in the unconcern of time.”

Will and Ariel Durant, The Lessons of History

Race, class, and gender also played an important role in deciding who became a historical actor. And while the Durants consistently looked beyond the individual, taking into account both social and economic factors, the feats of great men — from their military victories to literary accomplishments — seemed to have been of greater interest to the couple than the systemic injustices on which these hinged.

Where the Durants were once praised for their ability to condense, they are now accused of oversimplification. In an article published in the Vanderbilt Historical Review, Crofton Kelly argues that “in order to make their books accessible and interesting for ordinary people, the Durants de-emphasized important historical debates, and over-emphasized both the influence of famous individuals and the extent to which ‘history repeats itself.'”

The legacy of Will and Ariel Durant

Although they aimed for impartiality, the Durants were by no means passive observers. Outside of their writing, the couple frequently became involved in current events. They implored Woodrow Wilson not to become involved in the First World War and asked Franklin Roosevelt to stay out of the Second. During the rebellious phases of their youth, they went as far as to identify as anarchists.

At the end of the day, the Durants were and always will be a product of their time. While their texts seldom fall prey to any single ideological worldview, the narratives contained within them are most certainly presented through the lens of 20th century positivism and the unwavering conviction that history, in spite of its horrors, was an exceedingly beautiful thing.

Despite these criticisms, the legacy of the Durants has largely remained intact. The fact that the couple’s books continue to be read by intellectuals on both sides of the political spectrum is a testament to their integrity as historians, writers, and human beings. To say they have achieved their goal of bringing historical understanding to the common man would be an understatement.

Where other historians rush to defend themselves against external attacks, the Durants welcomed criticism as it made them conscious of their own biases and shortcomings. “Obviously we can only approach such total perspective,” Will wrote in What is Wisdom? Omniscience will always be unachievable, but the Durants showed that it can still be of use to academics as a guiding principle.