Herodotus’ mystery vessel turns out to have been real

(Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation)

- In 450 BCE, Greek historian Herodotus described a barge that’s never been found.

- When the ancient port of Thonis-Heracleion was discovered, some 70 sunken ships were found resting in its waters.

- One boat, Ship 17, uncannily matches the Herodotus’ description.

Artist’s concept of Thonis-Heracleion in its heyday. Yann Bernard © Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation

From [the acacia] tree they cut pieces of wood about two cubits in length and arrange them like bricks, fastening the boat together by running a great number of long bolts through the two-cubit pieces; and when they have thus fastened the boat together, they lay cross-pieces over the top, using no ribs for the sides; and within they caulk the seams with papyrus.

Herodotus wrote these words in his 450 BCE Historia to describe a kind of ship, called a “baris,” which he claimed to have seen under construction during his travels in Egypt. (Above is an excerpt — the entire passage is a bit longer at 23 lines.) His description constitutes an odd way to build a boat, and since no evidence of such a vessel had ever been discovered, some wondered if the esteemed Greek historian had made it up or got it wrong.

In 2000, though, the ancient port of Thonis-Heracleion was discovered at the western mouth of the Nile in an expedition led by maritime archeologist Franck Goddio. Thus far, his team has found about 70 ships dating from the eighth to the second century BCE, and guess what? Herodotus knew what he was talking about: Among the ships discovered in recent years was a baris, built just they way he’d described.

(Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation)

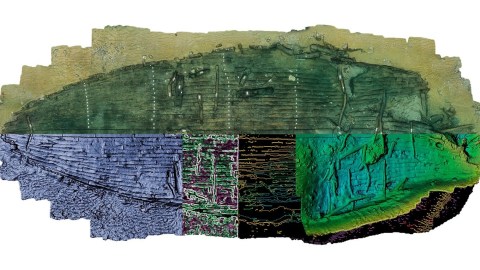

Ship 17

The vessel, dubbed Ship 17 by archeologists, dates to somewhere between 664 to 332 BCE. It’s been submerged in Nile silt for nearly 2,500 years, but is in amazingly good shape, allowing archeologists to uncover about 70 percent of the hull. Their research is being published by Oxford University’s Centre for Maritime Archaeology as a book, Ship 17: a baris from Thonis-Heracleion, by Alexander Belov, a member of Goddio’s exploration team.

Director of the Centre, Dr. Damian Robinson, tells The Guardian, “It wasn’t until we discovered this wreck that we realized Herodotus was right. What Herodotus described was what we were looking at.”

Exploring the sunken port. Image source: Christoph Gerigk © Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation

Word for Word

Making the identification a bit tricky were errors made in translation from the original Greek, probably since translators had no archeological materials on which to base their interpretation of Herodotus’ words. Explains Robinson, “It’s one of those enigmatic pieces. Scholars have argued exactly what it means for as long as we’ve been thinking of boats in this scholarly way.” For example, the long internal ribs Herodotus described had never been seen before, leading to confusion as to what he was talking about. “Then we discovered this form of construction on this particular boat and it absolutely is what Herodotus has been saying,” says Robinson.

Belov reports that a close comparison of the Historia text and the find shows Herodotus’ description matches “exactly to the evidence.” In his 2013 paper analyzing the baris’ navigation system Belov wrote, “The joints of the planking of Ship 17 are staggered in a way that gives it the appearance of ‘courses of bricks'” Herodotus described. Belov suggests it’s possible this baris came from the very shipyard Herodotus visited, its details fit so closely. However, this 27-meter baris is a little longer than Herodotus’, which may explain what few differences are evident, such as the Ship 17’s longer tenons, and the presence of reinforcement frames absent in the historian’s accounting.

Still, the find reveals Herodotus knew exactly what he was writing about.