10 of the most legendary rulers from ancient history

Karl Oderich, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

- We often dismiss ancient history and the people in it as too long past to be noteworthy.

- Some early rulers were so iconic that their names and works passed into legend and influenced others for centuries.

- Every person on this list contributed to the world you live in today.

A lot of people can be rather dismissive of ancient history, even using the term to refer to past events so remote as to be irrelevant. Nothing could be further from the truth, as the events and decisions made in antiquity continue to influence us to this day. To explore this, we’ll look at 10 of the most legendary rulers of ancient history, what they did, and why their decisions still matter.

For our purposes, “legendary” means “awesome” rather than “potentially not real.” A few kings and queens of old who may not have been real people, such as Gilgamesh, The Yellow Emperor, and the Queen of Sheba, are not included.

Additionally, what passes for “ancient” varies based on what area you’re talking about, so while all of the people on our list are long dead, a few of them were on the scene much more recently than others.

Hammurabi

Hammurabi was the king of Babylon who conquered all who opposed him and ruled with a code of laws assuring uniformity in justice. While his laws are not the oldest surviving ones and are not particularly good, they are among the earliest examples of a constitution known to man with an influence that is difficult to overstate.

After spending the early part of his reign strengthening Babylon’s walls and expanding the temples, Hammurabi took advantage of regional political intrigue and shifting alliances to conquer all of southern Mesopotamia—which came to be known as Babylonia—and forced the other power in the area, Assyria, to pay tribute.

He is most famous for his code of laws. The code, famously preserved on a monolith shaped like an index finger, shows Hammurabi receiving the law from the God of Justice. It goes on to describe 282 situations and prescribes legal action for each. It includes clauses for the presumption of innocence, the opportunity for both parties in a case to present evidence, and is the first known example of the eternally famous dictum: “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.”

Despite the attempts of the code to ensure equality, the harsh punishments are scaled based on who harms whom. A property-owning man would be punished less harshly than a slave, for example. Despite the disintegration of his empire after his death, his laws largely remained enforced at the local level and went on to influence the Romans, who wouldn’t barrow the idea of making the law publicly available until much later.

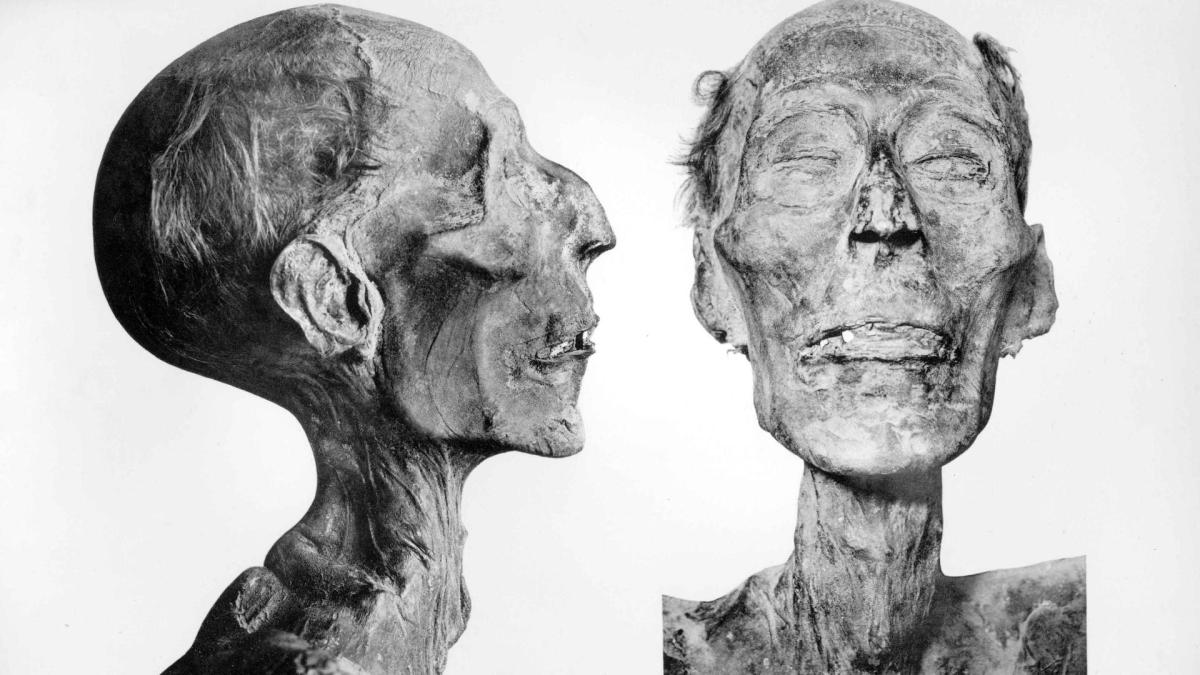

Hatshepsut

The second woman confirmed to rule as pharaoh and by far the most consequential, Hatshepsut had to overcome laws and traditions technically barring women from the role.

The wife, daughter, and sister of a king, Hatshepsut was also technically the wife of a God. Upon the death of her brother-husband, the pharaoh Thutmose II, Hatshepsut used her political cunning, regal background, and religious power to assume the title of pharaoh alongside her young son Thutmose III.

Like any good pharaoh, she embarked on a vast building campaign to legitimize her rule. No previous ruler (and perhaps only a few after) oversaw such an extensive series of building projects. Their vast scale suggests the country was particularly prosperous at this time.

Among these projects was her tomb, the extremely impressive Djeser-Djeseru.

Trade routes that had been disrupted prior to her reign were reestablished. This process included an expedition to the mysterious and wealthy Land of Punt. She also found the time to send military expositions to neighboring states. These ventures assured the prosperity which would define the 18th dynasty.

As with many pharaohs, there were attempts to erase any trace of Hatshepsut from the historical record. While these failed, they did cause some trouble for archaeologists a few thousand years later, who struggled to determine why some hieroglyphs referred to a queen.

Ramses II

Known to the Greeks, lovers of romantic poetry, and Alan Moore fans as Ozymandias, Ramses was one of the greatest rulers of Egypt, a country with enough great rulers to make that quite the achievement.

Like other great Egyptian rulers, Ramses’ reign featured monumental construction projects. Unlike most of his predecessors, his projects were on a scale not seen since the building of the Pyramids.

He built the new capital of Pi-Ramesses, a dazzling city and military base with which he kept an eye on his holdings in Canaan. Several massive temple structures, including the famous Abu Simbel temples, were dedicated at this time and featured colossal images, often of himself. He also ordered his artists to carve words and images deeper into stone than had been done previously to make them easier to see and harder to remove.

On the whole, his reign is considered by many art historians to be the high point of Ancient Egyptian culture.

Known as a great military leader, Ramses personally led his armies in Libya, Nubia, and Canaan. While his war with the Hittites didn’t go quite as well as his propaganda claimed, it did lead to the first peace treaty in human history.

During the Bronze Age Collapse, a period when most Mediterranean civilizations fell, Ramses was able to make Egypt one of two major civilizations to avoid failure and destruction at the hands of the mysterious “Sea Peoples” by defeating them in battle and securing the Egyptian borders. Without his leadership, Egypt may have suffered the same dark age as its neighbors and the world the poorer for it.

His reign was so long—he lived to be 96—that many Egyptians feared the end of the world at the time of his death. Nine later pharaohs would take his name in tribute to his legacy.

In addition to his impact in popular culture hinted at above, he is also frequently used as the pharaoh in film adaptions of the Exodus story, though there is no archaeological or historical evidence confirming such an event or that he was in charge when it happened.

The Duke of Zhou

One of the lower-ranking officials on our list is famous less for what he did and more for how he did it. The Duke of Zhou (pronounced “Joe”) was Confucius’ hero and laid the foundations for the first ruling dynasty in Northern China. As a result of Qin Shi Huang burning the imperial records, we don’t actually know much about the Duke, but his influence on Chinese history is significant.

The brother of the first king of the Zhou dynasty which ruled much of central China, the Duke became the regent for his young nephew after his brother’s death. Unlike most royal uncles in such a position, the Duke is famous for having not acted improperly. When his nephew came of age, the Duke gave up his power and went home.

During his regency, he put down a number of rebellions, expanded eastwards, codified Feudalism, established the holy city of Chengzhou, and legitimized Zhou rule with the idea of the Mandate of Heaven.

The mandate is an idea suggesting that rulers should be virtuous. When they are, heaven favors them and grants the nation prosperity. When they are not, natural disasters and other catastrophes will plague the nation. These disasters are a sign that heaven has abandoned a particular set of rulers and that they can, and should, be swept away by new ones who will do a better job. The Duke suggested that the Zhou, a new dynasty, had come to power this way and enjoyed heaven’s favor.

Confucius, the most influential thinker in Chinese history, later praised the Duke and claimed that his entire political philosophy was based on his life. The Mandate of Heaven, which would be refined by other philosophers, remained an important element in Chinese history and is still occasionally invoked to this day.

Pericles

The only member on this list to not rule as a king, Pericles was a general and the first citizen of Athens. While his command of the Assembly was firm enough that some commentators declared Athens “in name a democracy but, in fact, governed by its first citizen.”

While he was only ever elected as a general, Pericles was the leading member of the democratic faction of Athens for much of his life and dominated the political scene. After taking the reins of power, he oversaw the expansion of democratic rights, the issuing of salaries to those serving in government offices, the giving of land to the poor, and the creation of pensions for war widows.

This time span, known as the Age of Pericles, is considered the golden age of Athenian culture, when many playwrights, artists, sculptors, and philosophers were in Athens doing their finest work. It is this era that made Athens the leading city of ancient Greece.

His most famous act was technically one of embezzlement. He convinced the Athenians to use the treasury of the Delian League, a group of Greek city-states united for defense under Athenian guidance, to build a massive temple complex to replace an older temple for Athena. That complex, the Parthenon, remains a symbol of Ancient Greece and its golden era.

With his considerable oratorical skill, Pericles was able to maintain majorities in the Assembly even in the face of organized opposition. His famous “Funeral Oration” remains a landmark speech in the history of democratic leadership.

Alexander

No discussion of great rulers of the ancient world is complete without a reference to Alexander. The son of the king of Macedonia, a Greek-speaking kingdom just north of what the Greeks considered the civilized world, Alexander took control of his father’s kingdom and leadership of the Greek world after the old king was conveniently assassinated.

After becoming king and assuring the cooperation of the other Greek states, Alexander set out to conquer Persia, the neighboring empire which stretched from Egypt to India. After ten years of campaigning, in which he never lost a battle, Alexander conquered Persia, attempted to invade India, and laid out plans for a cosmopolitan empire blending eastern and western cultures together.

He died at age 33 of a mysterious illness before he could do so. His empire was then split up among his generals.

His conquests ushered in the Hellenistic period and made Athenian Greek the Lingua Franca of the eastern Mediterranean world. Greek ideas on art, culture, city planning, and education spread into new areas and fused with local ideas. This all but assured the primacy of Greek culture over all others in that part of the world and would guarantee its endurance even long after Rome conquered most of the Hellenistic kingdoms that sprung up after Alexander’s death.

Qin Shi Huang

The first emperor to unite China and the initiator of several ideas later rulers would emulate, Qin Shi Huang technically ended what is thought of as ancient Chinese history and ushered in the imperial era.

After becoming king of one of the seven warring kingdoms during the aptly named “warring states period,” he united the seven under his rule through a brutal military conquest. Assuming the title of Emperor of China, he abolished feudalism, redrew the administrative maps, and replaced hereditary officials with ones selected for their merits.

He then began an extensive public works campaign, which included building the first iteration of the Great Wall and a canal linking the Yangtze and Pearl Rivers. His government also found the time to build extensive roadways, reform the coinage, and redistribute land to the peasants.

Qin Shi Huang also had a dark side. He famously burned the imperial library and all of its texts, which made him, or the legalistic philosophy his government followed, look bad. The flourishing of ideas that defined warring states era philosophy ended during his rule, though the ideas he sought to suppress, including Confucianism, merely went underground.

Toward the end of his life, the emperor began a search for immortality elixirs. It is believed that some of these elixirs contained mercury, which may have hastened his death. His tomb is the home of the famous terracotta army in Xian.

Boudica

Boudica was the queen of the Celtic Iceni tribe, famed for leading her people in revolt against the Romans. While she was defeated, her victories still inspire those fighting for freedom two thousand years later.

Her late husband had willed his petty kingdom to both Rome and his daughters in hopes that this arrangement would assure some form of independence. The Romans instead moved in and brutally suppressed the population. Appealed by this betrayal, Boudica led the Iceni and their neighbors in rebellion.

Their first stop was Colchester, which they systematically demolished. When the 9th legion was sent to put down her rebellion, she led her troops in battle against them. The 9th was almost completely annihilated, with only a few officers and horsemen escaping.

Her army advanced, burning Roman settlements in their wake. Roman officials fled as the city of Londinium, now known as London, was wiped off the map.

It was shortly after this that the Romans counterattacked with a large force somewhere outside of modern London. Boudica, having expressed her desire to win or die as a freewoman, led the rebels from her chariot and perished alongside them.

She is unique among the members of this list for being better known as a symbol of the fight against oppression than for the constructive elements of her reign. Her image returned to prominence during the English renaissance when England, led by Elizabeth I, faced invasion. The following centuries only added to her fame.

Today, statues of Boudica can be found in several prominent locations in London.

Trajan

The second of the “Five Good Emperors,” Trajan expanded Roman territory to its greatest extent, stretching from Scotland to Kuwait. Between his military successes and domestic policies, the Roman Senate found it proper to declare Trajan Optimus Princeps- the greatest ruler.

Adopted by a childless emperor as an adult, Trajan was the first Roman emperor to not be born in Italy. Coming to power during an era of relative prosperity, Trajan spent much of his time on public works projects and warfare.

On the domestic front, he rebuilt the road system which Rome is so famous for, gave the city of Rome—now home to a million people—a new forum and lovely column, financed vast infrastructure projects, and granted pardons to those persecuted under the reign of Domitian a few years prior.

On the battlefield, he led the legions in three large wars. These ended in the conquest of modern Romania, Armenia, Iraq, and Kuwait. In celebration of the Romanian conquest, he put on a festival featuring 10,000 gladiators.

Pacal

A Mayan king whose 68-year rule is the fifth-longest reign in history, Pacal turned a minor city-state into a powerhouse and built some of the great Mayan temples. Known as K’inich Janabb’ Pakal in his own language, his rule was one of the high points of the Mayan civilization.

Coming to power at age 12 after a period of regency under a mother who would later serve as his chief advisor, Pacal legitimized his rule with a series of massive building projects. These included the great Temple of the Inscriptions in his capital of Palenque, which would later serve as his tomb. He also forged alliances with other Mayan rulers that would bring Palenque to prominence.

His capital city, while a smaller Mayan urban center, features some of the finest artwork that civilization is known to have produced. The majority of the city has not been fully discovered, and what archaeological wonders lie waiting in the jungle is anyone’s guess.

This article was originally published in January 2021. It was updated in September 2022.