California condor: How conservationists rescued a bird that was lost in time

- When the population of wild California condors dropped so low that it risked harming the species’ ability to reproduce, conservationists sprung into action.

- All remaining wild condors were captured and bred in captivity before being reintroduced into their natural habitats.

- The conservation mission, while both expensive and expansive, proved successful, effectively saving the ancient bird from the brink of extinction.

On April 19, 1987, biologist Jan Hamber was chasing the world’s last wild California condor through Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge in Maricopa. After an afternoon spent soaring at high altitudes, the bird eventually landed near the carcass of a stillborn calf, which Hamber’s team was using as bait. The bird observed the carcass but did not take a single bite. When it flew off to roost for the night, Hamber began setting up a trap.

Intimately familiar with the California condor’s feeding patterns, Hamber figured the bird would sleep first and feed later. She was right: When it returned to the carcass the following morning, one of Hamber’s colleagues fired a net over its head using a camouflaged, remote-controlled cannon. The bird, also known as AC9, had finally been caught. Next stop: the zoo.

Capturing AC9 was the last step of the first phase of what would become one of the most expensive and elaborate conservation efforts ever sponsored by the United States government. It involved catching the 27 California condors that were still alive in the wild so that biologists could manage and manipulate their reproductive cycles in a controlled environment.

Many experts, Hamber included, had their doubts. The rehabilitation program had no scientific precedent, meaning there was no way of knowing whether adult condors would actually reproduce. The experts also questioned whether their children, born and raised in captivity, would know how to survive in the wild after they were reintroduced into their “natural” habitats.

At the same time, the California condor had been declared a critically endangered species. Its existence was being threatened by a number of factors, from their own evolutionary history to the encroachment of human civilization. In many ways, the rehabilitation program, while drastic, was the bird’s last and only hope. Luckily, though, it was also a huge success, boosting the condor’s population and reintroducing it to places it had once occupied but no longer did.

The extinction of the California condor

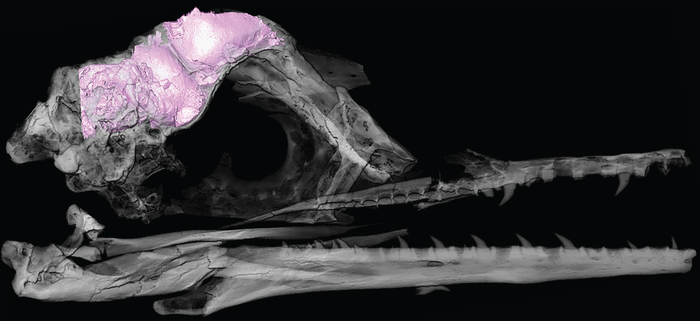

The California condor’s monstrous size may well be its greatest asset. Nobody knows how condors managed to get as big as they are — with a wingspan of roughly 9.5 feet — but a prominent theory holds it had something to do with the way in which they feed. Condors are scavengers that subsist on carrion, and they might have evolved to grow larger in order to scare off and steal from large predators, such as wolves and cats.

Where several other large birds eventually became landlocked as a result of their increasing body mass, the condor managed to stay airborne thanks to some clever tricks. Instead of flapping its wings to take off into the air, the California condor glides off cliff tops and uses updrafts to gain altitude. This allows the scavengers to preserve as much energy as possible — a luxury that birds of prey, which have to chase and hunt their meals, cannot afford.

These adaptations allowed the California condor to stick around for tens of thousands of years. When their numbers started to dwindle across the 19th and 20th centuries, researchers had a number of potential causes to choose from. Poaching and habitat destruction undoubtedly played a key role, as did collisions with power lines and exposure to agricultural chemicals like DDT.

Many condor corpses also showed signs of poisoning — lead poisoning, to be precise, derived from bullets human hunters left in their abandoned game. This game attracted condors, which — owing to their size — often swallowed bits of shrapnel without realizing it. That shrapnel would then be broken down by the bird’s extremely potent stomach acids, releasing chemicals that could poison their bloodstream.

When the population of wild California condors became so small that the genetic diversity among future generations would be put at risk, the decision to catch all 27 remaining specimens was made. Their numbers would be replenished in captivity, where researchers could facilitate reproduction at a rate faster than Mother Nature did. Once replenished, the freshly bred condors would then be reintroduced into their natural habitats.

Help from the Andes

The 27 birds were split between two institutions, the San Diego Wild Animal Park and the Los Angeles Zoo, where their species continues to be bred in captivity to this day. The program, which didn’t begin releasing birds into the wild until the early 1990s, cost more than $35 million, making it one of the most expensive conservation projects that the U.S. government has ever financed. By 2007, the program had an annual cost of more than $2 million.

The project had a number of ambitious goals. It not only tried to increase the population of California condors in general, but also aimed to reestablish wild colonies in two distinct areas: California and Arizona. By the time that species reintroduction rolled around, each state would be given 150 birds, which included no less than 15 breeding pairs.

These ambitious goals, however, were quickly offset by the California condor’s complicated reproductive system. Condors produce less frequently than other birds, and in fewer quantities. The condor’s incubation period can last up to 60 days, and young birds — due to the size of their eggs — typically don’t have any siblings. Condors also have long lifespans, which means the young take longer to reach sexual maturity. For the California variety, this happens between the ages of five and six.

Ultimately, experts were able to speed up the bird’s reproductive rate, saving the program a handful of years and millions of dollars. Here’s what they did: Whenever a condor laid a new egg, they quickly removed the egg from her nest. Noting its absence, the condor would be stimulated to lay a second clutch. As the condor raised her second child, caretakers would then raise the first using a hand puppet that looked and smelled like its mother.

Before the newest generations of the California condor could be reintroduced into the wild, the program had to make sure the ecosystem could support their reinforced numbers. Fortunately, they were able to test it with a flock of Andean condors. The California condor’s closest living relative, the Andean condor, keeps to South America. Although also considered a vulnerable species, their numbers have improved significantly thanks to conservation efforts and educational programs — so much so that a portion of their global population could be spared for the experiment.

In order to make sure that this North American flock remained under control, the researchers released only females. When, after more than a year of observation, the population seemed to have stabilized and even acclimated to the new environment, the Andean condors were captured and returned to their native countries. Once they had vacated, the reintroduction of the California condor could officially begin.

Current condor populations

The program proved to be a huge success. By 2010, the population of wild California condors had increased from 27 to 100. The following year, that number climbed to 205. In 2014, the number of wild condors surpassed the number of condors in captivity. The year 2015 marked yet another milestone: In the wild, the number of condor births now exceeded the number of deaths. The California condor had at long last been saved from genetic meltdown.

When the rehabilitation program was first conceived, people wondered whether condors raised in captivity could survive once they were released into the wild. In order to make sure they would, the caretakers kept human contact to an absolute minimum. They only interacted with the chicks by way of the hand puppet, and were quickly transitioned to aviaries so they could acclimatize to the living conditions of their final destination.

Starting in 1994, the program’s caretakers also began training captive condors to stay clear from humans and powerlines. (Powerlines, so they wouldn’t land onto them and accidentally electrocute themselves. Humans, so the likelihood of contracting lead-poisoning from a hunter’s kill would lower.) In 2008, California passed a law prohibiting hunters from using lead bullets whenever they were hunting in or near a bird’s known habitat.

Rehabilitating California condor populations in North America was a global enterprise, requiring the expertise of scholars from various fields located across the world, and involving precise coordination with another, equally complex and internationally minded conservation attempt conducted in South America.

Because of its dinosauric size, the California condor almost looks as if it has gotten lost in time. However, this is not the case. While most of the species that they originally lived alongside have gone extinct, the condor continued to exist. Its resourcefulness as a scavenger allowed it to survive for thousands of years, and should theoretically enable it to survive into the near future.