Archaeologists Might Have Discovered St. Nick’s Remains in a Hidden Tomb

The port city of Bira, Italy has long been considered the final resting place of Saint Nicholas, the fourth-century saint whose life inspired the story of Santa Claus. His remains are located in the Basilica di San Nicola, a church that was erected after Italian merchants smuggled his bones to the city from present-day Turkey in the 11th century. The Basilica di San Nicola is now a popular tourist spot that attracts thousands of visitors every year.

Except, those merchants might have snagged the wrong bones.

Archaeologists using CT-scanning and geo-radar technology claim to have discovered a hidden tomb located beneath the St. Nicholas Church in Demre, Turkey that could contain the authentic remains of the saint. Before unearthing the tomb, an excavation team will have to carefully remove mosaics on the church floor.

“We have obtained very good results but real works start now,” said Cemil Karabayram, Antalya Director of Surveying and Monuments, to the Hurriyet Newspaper. “We will reach the ground and maybe we will find the untouched body of St. Nicholas. We appointed eight academics of different branches to work here.”

If their prediction is correct, the Demre district will see a massive boost in tourism, Karabayram added.

Damaged tomb in the St. Nicholas Church in Demre.

As researchers shed light on the life and death of Saint Nicholas, it begs the question: How did we take the story of a real-life man and turn him into the jolly, chimney-scaling Santa Claus we know today?

Saint Nicholas from Man to Myth

The details of St. Nicholas’ life are scant, but most accounts agree on some key points: He was born in Patara, Lycia near present-day Turkey around 280 A.D. He lost both parents at a young age and became a devout Christian, and he used his inheritance to help the sick and poor. After returning from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, St. Nicholas was imprisoned during the persecution of Diocletian. He was eventually freed and served for decades as the Bishop of Myra, even attending the Council of Nicea in 325 A.D.

Russian icon depicting Saint Nicholas with scenes from his life.

What gave rise to the legend of Santa Claus, though, were the tales of his good deeds. One such story tells of three sisters who were destined for slavery because their father couldn’t afford dowries to offer any prospective husbands. (Life was considerably less jolly in the times of real Santa.) But then, on three separate occasions, bags of gold mysteriously fell through the chimney of their home and landed in stockings left near the fireplace to dry. The women could now marry and avoid slavery, all thanks to Saint Nicholas.

Saint Nicholas died in 343 A.D., but he lived on to be one of the most revered saints in Christianity — by Catholics and Protestants alike. Sailors claimed him as their patron saint. Churches were named after him in the East and the West, including 300 in Belgium alone. His tomb in Myra became a popular pilgrimage site, until 1087 when Italian merchants stole his remains and brought them to Bari.

It wasn’t until the 16th century that he became known as “Father Christmas” in Europe. Then, in the 18th century, the story of St. Nicholas – or Sinterklass – sailed to the U.S. by way of Dutch immigrants. A New York newspaper reported in 1773 and 1774 that a group of Dutch families had congregated to celebrate the anniversary of Saint Nicholas’s death on December 6.

Washington Irving

In 1809, the lawyer-turned-writer Washington Irving published his first book A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, in which he satirized the traditions of Dutch Americans and their patron saint, Saint Nicholas. In the book, a Dutch official sees a vision of Saint Nicholas in a dream:

And the sage Oloffe dreamed a dream—and, lo! the good St. Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees, in that self-same wagon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children. And he descended hard by where the heroes of Communipaw had made their late repast. And he lit his pipe by the fire, and sat himself down and smoked; and as he smoked the smoke from his pipe ascended into the air, and spread like a cloud overhead. And Oloffe bethought him, and he hastened and climbed up to the top of one of the tallest trees, and saw that the smoke spread over a great extent of country—and as he considered it more attentively he fancied that the great volume of smoke assumed a variety of marvelous forms, where in dim obscurity he saw shadowed out palaces and domes and lofty spires, all of which lasted but a moment, and then faded away, until the whole rolled off, and nothing but the green woods were left. And when St. Nicholas had smoked his pipe he twisted it in his hatband, and laying his finger beside his nose, gave the astonished Van Kortlandt a very significant look, then mounting his wagon, he returned over the treetops and disappeared.

The New York Historical Society had already designated Saint Nicholas as the patron saint of New York a few years before, but Washington’s book helped to animate the saint in the minds of New Yorkers, and thus encourage them to adopt the Dutch tradition as a holiday. So, yeah, Christmas might not exist as we know it if Washington Irving had stuck with law.

In 1822, an Episcopal minister named Clement Clarke Moore helped further thrust Christmas into the culture by writing a poem for his children titled ‘A Visit From St. Nicholas’ (also known as ‘’Twas the Night Before Christmas’).

The poem was published anonymously in an upstate New York newspaper and became wildly popular, selling millions of copies in the years that followed. (Moore is typically credited with writing the poem, but there’s a good case to be made that Major Henry Livingston was actually the author.)

The writings of Irving, Moore and Charles Dickens brought the story to popular imagination, but the image of Santa Claus as we know him — fat, rosy-cheeked, bearded, white — wasn’t solidified until the 1860s when a political cartoonist named Thomas Nast created a series of paintings depicting the saint for Harper’s Weekly. His images also gave Santa Claus a home — the North Pole. Why? Arctic expeditions were a new and popular feat in the mid-19th century, and the region was regarded mysteriously as one the planet’s last unexplored territories.

What isn’t quite known is when Santa Claus became known as a full-fledged home invader, as Megan Garber writes in The Atlantic:

“What is clear, though, is that his status as a participatory myth is a relatively recent invention: It came about, like the fur-and-reindeer images, in the 19th century. Santa, it seems, arose with industrialization, with the economic plenty that came with it, and with something else prosperity inspired: changing notions about the family and the children’s place within in. Santa, as we know him today, was born during a time that was rethinking and reimagining and in many ways reinventing that oldest of things: childhood.”

In any case, the next major shift in the depictions of Santa Claus came with the Coca-Cola ads of the 1920s.

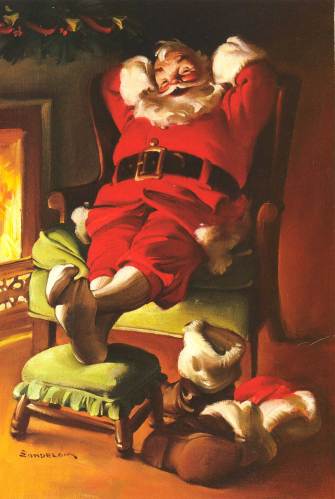

The initial ad campaigns were based off Nast’s stricter-looking Santa, but in 1931 an advertising executive named Archie Lee decided to depict him in a more wholesome light. An illustrator named Haddon Sundblom was commissioned to do the job, and his images would go on to be published in national publications like The Saturday Evening Post, National Geographic and the New Yorker.

Sundblom is often credited as the creator of the modern American Santa Claus, who, short of a few Hollywood experiments, has remained jolly, generous and rosy-cheeked for almost a century.