All animals on Earth feature a recognizable body plan. Give any 10-year-old a picture of a common animal, and she will instantly be able to place it into a specific group. Sporting eight arms and swimming the ocean deep? You’re an octopus. Lurking the savannah, slender and with a mean bite? You’re a big cat. Buzzing and barely discernible until you land on my picnic table? You’re a bug.

The world bursts with biodiversity, but it is also tightly wound with pattern and order.

Travel back 500 million years, however, and the scenery you encounter would be much more chaotic. You would be a stranger in a peculiar place, surrounded by creatures that are very weird indeed. You would be hard-pressed to relate to anything that you saw.

That is, unless Auroralumina attenboroughii happened to float by. Suddenly, a flash of recognition: “Hey, I know you! You’re an ancient jellyfish.”

Marine secrets, hidden in a forest

Today, we do not see A. attenboroughii pulsing in the ocean, but we did find it stenciled into some rock. Paleobiologist Philip Wilby and other researchers from the British Geological Survey discovered this rock deep in the hills of the Charnwood Forest, an area in central England that is well known for being a hotbed of ancient diversity from the Ediacaran period, 635 million to 541 million years ago. The scientists aged the rock, and the fossil within, using methods based on the natural decay of uranium into lead. Their results age the fossil between 557 million and 562 million years, placing A. attenboroughii deep within the Ediacaran period.

A. attenboroughii’s species name may sound familiar. The team that discovered the specimen named it after famed English naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough to honor his work in raising awareness of the Charnwood Forest. As the team told Science, Attenborough spent his youth exploring the area, developing the passion for naturalism that he would later share with generations of eager viewers. The genus name, Auroralumina, uses Aurora, Latin for dawn, to represent the significance of the fossil’s age and its evolutionary position. They added lumina, Latin for light, because the specimen resembled a lit-up torch, with a wide stalk tapered downward, and tentacles spread like an undulating flame.

This might seem like an epic name for a fossil found in an English forest — but A. attenboroughii certainly lives up to it.

In a new paper published by the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, a group of researchers led by paleobiologist Francis Dunn demonstrates that the specimen has the body plan of a cnidarian, an ancient group related to modern corals and jellyfish. As such, A. attenboroughii is the oldest known relative of any group of animals that still exists today. Its discovery shakes up the well-established theory that animal body plans were fixed during the Cambrian explosion, which occurred tens of millions of years after A. attenboroughii floated the ocean’s depths.

Ancient jellyfish

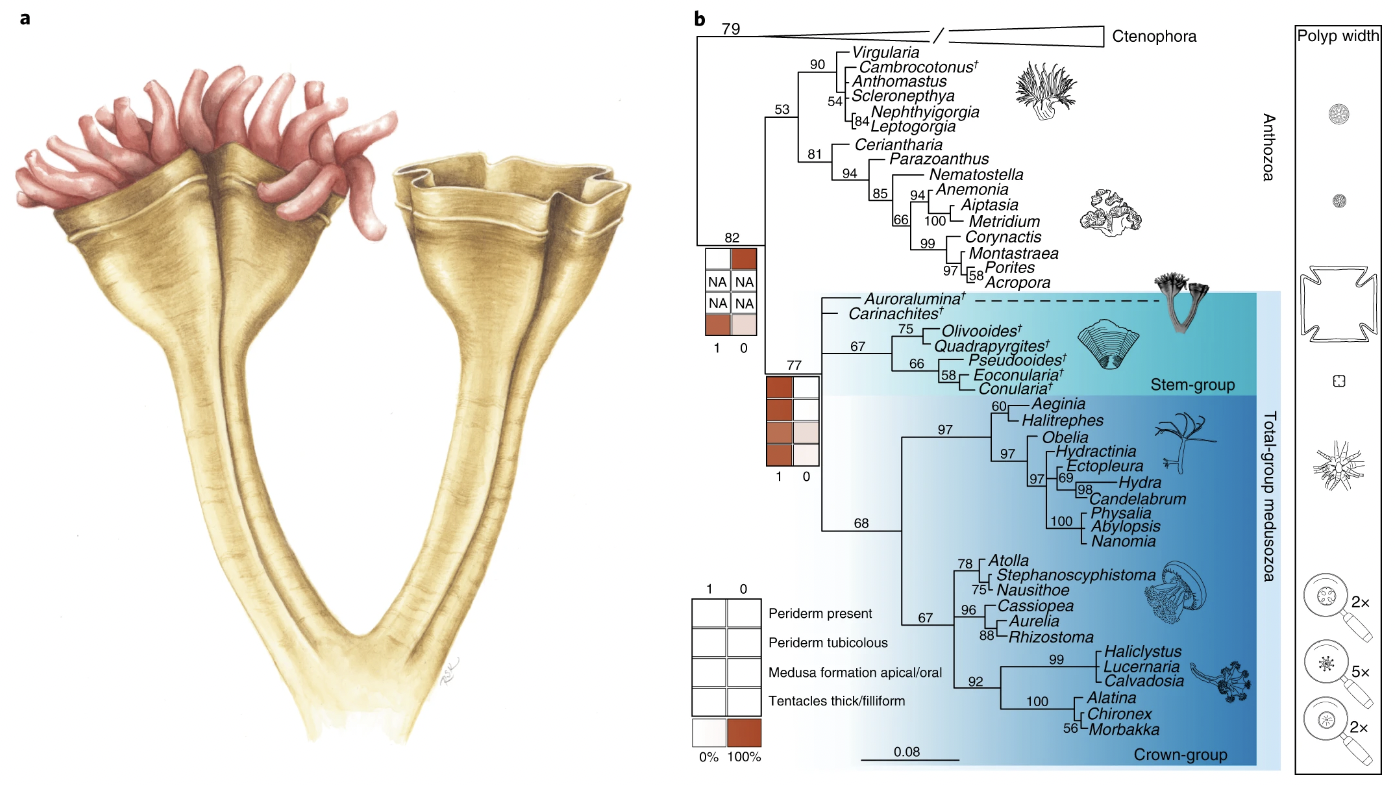

The A. attenboroughii specimen measures 20 cm long — approximately the length of a normal toothbrush. The specimen has two well-defined stalks that bifurcate from an area that was not preserved. At the top of each stalk is a dense crown of long, overlapping structures that the researchers identified as tentacles.

When examining the specimen, the team considered the consequences of pressing a three-dimensional organism onto a two-dimensional surface. Accounting for this led the researchers to believe that the left and right stalks were identical. Thus, the specimen was likely tetraradial, meaning it was symmetrical around four corners emanating from the center. Modern jellyfish share this feature.

Because the specimen is preserved in a lateral view, the researchers could not analyze the arrangement of the crown or the structures within it. They noted that these projections most closely resemble the tentacles of living animals, but instead of being preserved as individual tentacles, they appear to be one larger, compound structure.

Finally, based on the differences in the preservation of the fossil, the researchers concluded that the two parts — the stalk and the crown — were constructed of different materials. Whereas the stalks were rigid, the crown was much less resilient and made of softer tissue.

When the team considered these characteristics, they concluded that Auroralumina was a cnidarian, the group that contains modern jellyfish and corals. A. attenboroughii seemed to have perished in its polyp life stage — a time when cnidarians adhere to the ocean floor and use their tentacles to snatch food such as floating plankton.

Ahead of its time

The researchers made a cast of the fossil. They used this cast to create a computer model of the creature, in order to examine it under different lighting. They then used its physical features to place it on a phylogenetic tree. The analysis placed A. attenboroughii in the medusozoan stem group of the cnidarians.

A. attenboroughii’s anatomy is distinct from all other known Ediacaran fossils. In fact, it shares a combination of characteristics with early Cambrian forms of confirmed cnidarians. If the researchers had to make an assessment based only on the specimen’s physical features, without considering the age of the fossil, they would have placed A. attenboroughii well within the group of Cambrian cnidarians.

However, the Cambrian cnidarians, which had been thought to be the very oldest organisms in the group, emerged tens of millions of years after A. attenboroughii was fossilized. Based on our current understanding, A. attenboroughii should not have evolved yet.

A. attenboroughii is not the first Ediacaran fossil that researchers speculate has cnidarian roots. For example, Haootia quadriformis, from Newfoundland’s Bonavista Peninsula, dates to a similar era. However, H. quadriformis was preserved poorly, and paleobiologists do not have enough material to claim with any confidence that the specimen has cnidarian affinity. Other Ediacaran cnidarian candidates like Cloudina and Corumbella failed to garner the backing of the scientific community for similar reasons.

But A. attenboroughii is the total package: It is preserved well enough to confidently conclude its cnidarian origins, and it fossilized in a material that is easy to age accurately. Though the fossil is incomplete, A. attenboroughii is a very significant find and sheds light on the early evolution of several key cnidarian traits.

The discovery of A. attenboroughii extends the fossil record of early cnidarians by nearly 25 million years, pushing the group’s history deep into the Ediacaran period. Notably, A. attenboroughii appeared tens of millions of years before the Cambrian Explosion, the time when animal diversity exploded. Before this discovery, scientists agreed that the animal body plans we see across the corners of the Earth today were all mapped out during the Cambrian Explosion. As Dunn told Science, if other researchers corroborate their claims, “our fossil becomes the oldest animal with direct living descendants in the fossil record—full stop.”