Amenhotep I: CT scans get a glimpse inside the mummy

- Amenhotep I ruled over Egypt roughly 3,500 years ago.

- His brittle mummy has never been unwrapped, but CT scans allowed researchers to peek underneath the bandages.

- The scans shed light on the pharaoh’s physical features, his embalming process, and posthumous encounters with graverobbers.

Surprisingly little is known about the life of Amenhotep I, who ruled over Egypt from 1525 to 1504 BC, an impressive 21 years. We know that he had been the second king of Egypt’s 18th dynasty, that he was not expected to inherit the throne, and that he may have ruled alongside his mother for a brief period when he did.

We know that his name means “Amun is satisfied” — Amun being one of eight primordial deities in Egyptian mythology, as well as the god of air. Thanks to surviving hieroglyphs, we also know that Amenhotep strived to maintain his empire’s rapidly expanding borders, waging war with ancient Libya and the kingdom of Kush.

The lack of documentation surrounding Amenhotep may have had something to do with the fact that his reign was relatively peaceful and prosperous, marked only by minor improvements in government administration and the construction of a handful of new temples such as the temple of Amun at Karnak.

Historians suspect that more could be discovered about Amenhotep if we can find his original tomb. However, this is easier said than done. There is no known evidence, textual or archaeological, pointing to the original tomb’s location. On top of that, Amenhotep’s body has been moved around several times, including by subsequent pharaohs who sought to protect his remains from graverobbers.

Fortunately, Amenhotep’s mummified remains can still offer substantial insight into the historical period they hail from. Unfortunately, studying these remains has proven difficult for one reason: when Amenhotep was buried, his mummy was fitted with a painstakingly crafted cartonnage face mask. This mask still sticks to Amenhotep’s face today, and researchers fear that any attempt to physically unwrap the mummy could risk damaging or even destroying the priceless artifact.

Previous attempts

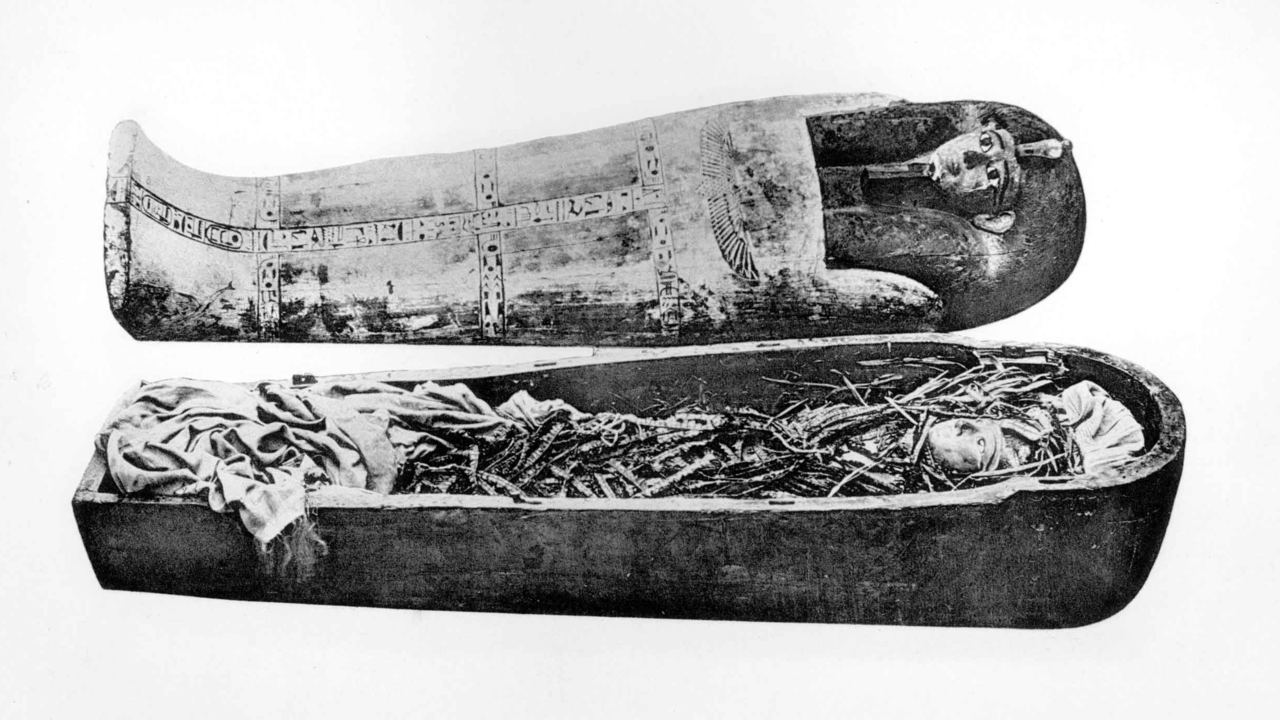

While researchers were hesitant to look at the mummy itself, they wasted no time examining his immediate surroundings. Amenhotep lay inside a sarcophagus that was decorated with hieroglyphic inscriptions or dockets that mentioned not only his name but also the fact that this coffin, despite looking considerably ancient, was not the pharaoh’s original.

According to the dockets, Amenhotep I had been rewrapped and reburied at Deir el-Bahari Royal Cache by the 21st Dynasty, which reigned from 1069 to 945 BC. The dockets even record the names of the people that rewrapped the pharaoh: Pinedjem I, a High Priest of Amun in service to the 21st dynasty, and his son Masarharta.

This reburial may well have marked the last instance that Amenhotep’s body was seen by other people. Today, it is one of only a handful of mummies that has not yet been unwrapped in modern times, and everything we know about it has been inferred from technologies that can peek underneath the bandages without removing them.

Once exhumed, the mummy was kept at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In 1932, X-rays determined that the pharaoh had been between 40 and 50 years old at the time of his death. After X-ray technology had advanced considerably, Amenhotep was scanned again. This time, the age estimate was much younger; the conditions of his teeth especially suggested that the pharaoh could not have been older than 25 when he died.

Perhaps the most revealing study yet came out in late 2021. Two researchers, Sahar Saleem and Zahi Hawass, conducted a CT scan to generate detailed, three-dimensional models of the mummy’s head mask and bandages as well as the body hidden underneath.

The body of Amenhotep I

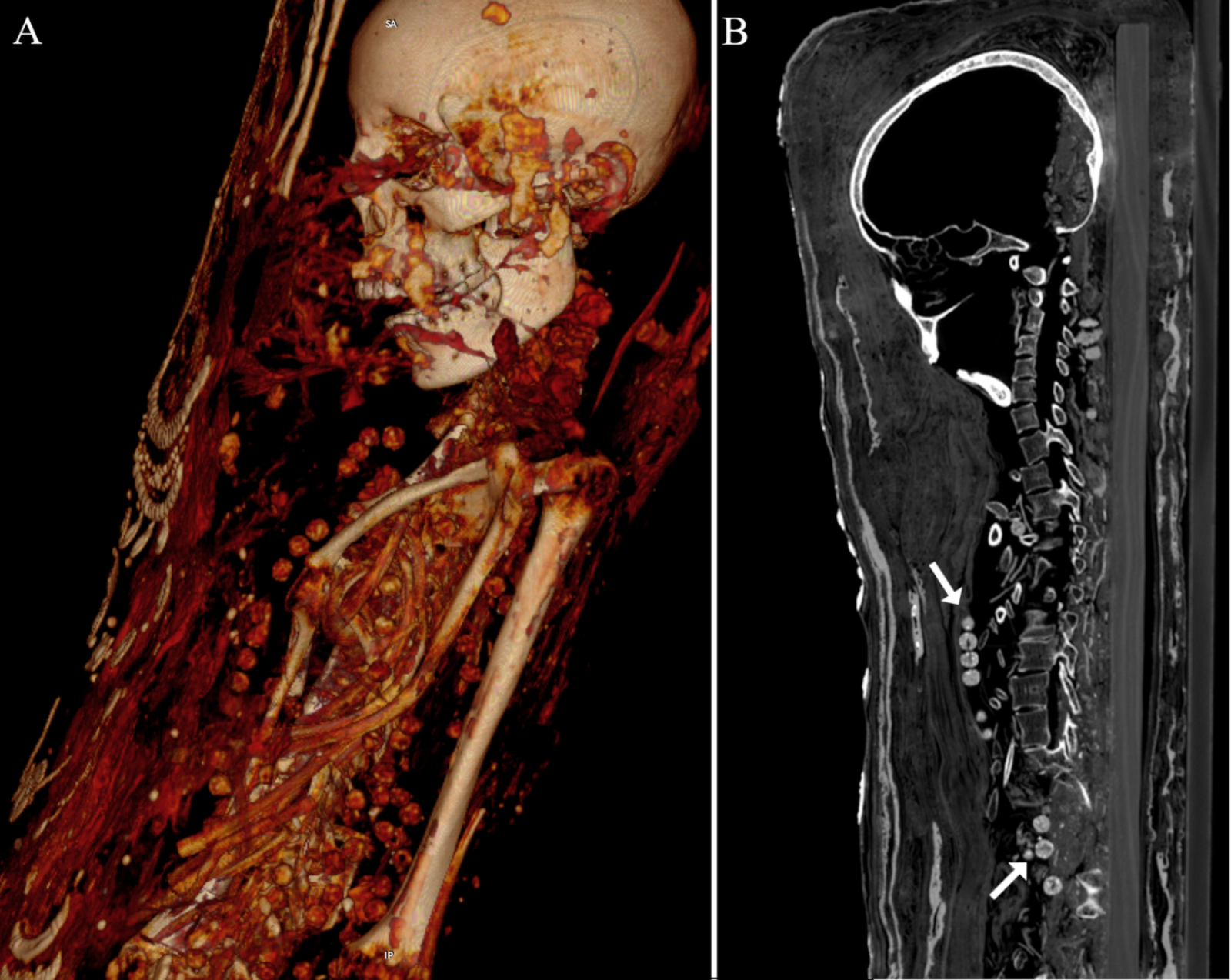

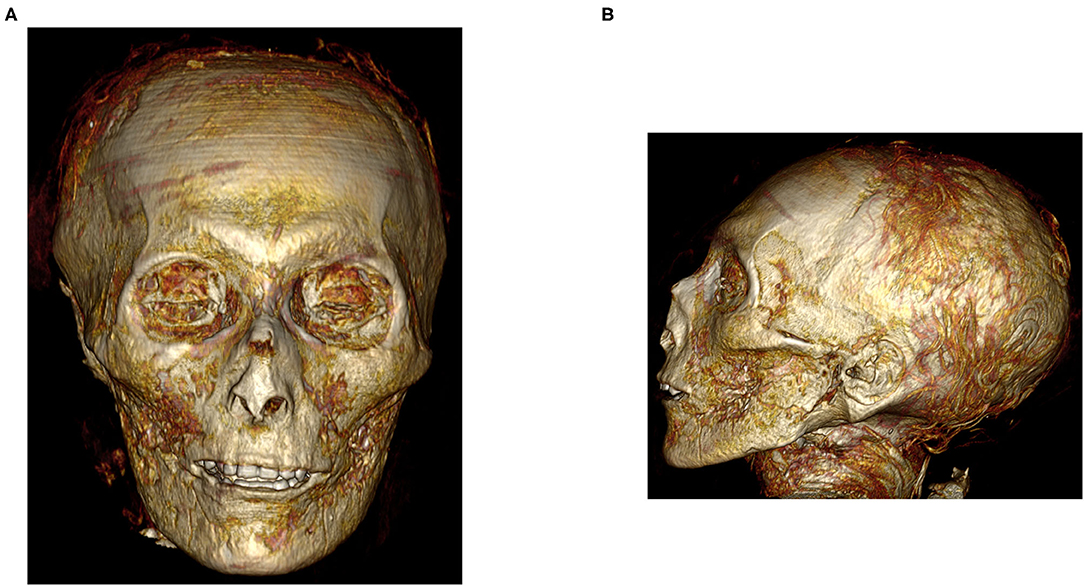

The researchers’ study, which was published in the online journal Frontiers in Medicine, include clear and detailed representations of the pharaoh’s body. A side profile of Amenhotep’s skull inside the coffin is accompanied by the following description:

“The mummy of Amenhotep I has an oval face with sunken eyes and collapsed cheeks. The nose is small, narrow, and flattened. The upper teeth are mildly protruding. The chin is narrow. The ears are small; a small piercing is noted in the lobule of the left ear. Few coiled hair locks are seen at the back and sides of the head.”

The scans also reveal postmortem injuries. Researchers identified a fracture of the cervical spine from when the mummy was decapitated by graverobbers. The right wrist is dislocated, while the left hand has been severed completely from the rest of the body. Numerous fingers are missing, likely stolen.

As with other mummies, Amenhotep’s organs were removed through a single left flank incision. Embalmers used a variety of materials to fill the hollow body. Scans show that the pharaoh’s body contains products of various molecular densities, including linen fibers and linen packs that were treated with resin. Using the length of his tibia, the researchers concluded that Amenhotep must have stood 168.5 cm (5′ 6″) tall.

Unwrapping ancient history

Thanks to considerable advances in scanning technology, the researchers were able to debunk previous assumptions about Amenhotep’s mummy. Perhaps the most significant of these is the pharaoh’s elusive age. A new estimate of 35 years was made, based on the “closure of epiphyses of all the long bones” and “the morphology of the surface of the symphysis pubis,” not to mention the perfect state of the teeth.

The scans also revealed things about Amenhotep’s mummy that previously went unseen, including the fact that the brain was never removed from the skull. Normally, brain tissue is removed through the nostril. This operation was practiced as early as the fourth dynasty, though it was not carried out on Amenhotep. Other key parts of the mummification process seem to be absent as well. “To make the corpse more lifelike,” the researchers write, “the embalmers of the royal mummies dated to the New Kingdom usually used packs in the eyes, nose, mouth, and under the skin,” yet “this study shows that the mummy of Amenhotep I has not received such a treatment.”

Notably, Amenhotep’s mummy was found clinging to several amulets hidden underneath his bandages. The fact that the pharaoh is still in possession of these burial gifts is quite astounding. According to papyrus scrolls found at the Medinet Habu temple, tombs were always in danger of being raided, not only by wandering graverobbers but by members of the pharaoh’s own burial group. Then, as now, good help is hard to find.