Why social design projects fail

- Despite the dual blessings of funding and enthusiasm, many social design projects fail to bring measurable change to people’s lives.

- A common miscalculation of such projects is the substitution of understanding with empathy.

- Another is favoring faddish innovations over the development of long-term, incremental progress.

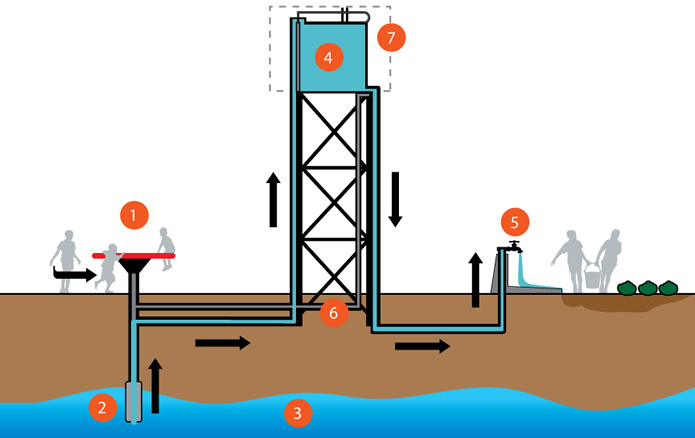

The PlayPump was a simple device with an intrepid promise. The device was a merry-go-round connected to an underground pipe. As children played on it, the pipe would pump groundwater into a nearby storage tank where it could be accessed from a hand pump in the village. The promise: Solve the water problems of Africa’s most underprivileged communities.

Based on that promise, PlayPump International received a deluge of support and funding. In 2005, PBS Frontline ran a flattering report on how the device would turn “water into child’s play.” It won the World Bank Development Marketplace Award grant in 2000, and the U.S. government pledged $10 million. Millions more in private donations poured in alongside endorsements from the likes of Laura Bush, Jay-Z, and Steve Case. All toward the goal of installing 4,000 PlayPumps by 2010.

When 2010 arrived, PBS Frontline returned to report on PlayPump’s progress. This time, the article was titled “Troubled Water.” Care to guess how well the grand (and expensive) experiment in social design went?

Nor is PlayPump’s story exceptional. The first two decades of the 21st century have seen numerous social design projects make little difference or even harm the lives of the people they hoped to help.

Two common miscalculations in social design

What’s especially mystifying about these many missteps is that social design seems to have a blue-ribbon formula for success — to say nothing of the cash and enthusiasm to see the project through.

As described by Cheryl Heller, a business strategist and designer: “Social design is the application of the design process to human relationships and invisible dynamics between people and between people and the environment. It’s not terribly unlike the process that’s used to create products and services, the physical things that people know, but it’s done at scale.”

And that formula has had its success stories. In her interview, Heller pointed to Jeffery Brown, a fourth-generation grocer and future-Philadelphia mayoral candidate, as one such example. Brown founded the nonprofit UpLift, which trains returning citizens and guarantees them a job in one of Brown’s grocery stores. As of 2022, the nonprofit has helped more than 700 returning citizens find employment.

So then, why is it that for every UpLift, there seems to be a PlayPump International, Millennium Villages Project, or another social design failure? The modest answer is that social design is a far more formidable problem than developing a car, phone app, or superior panini press.

As Michal Hobbes points out in the New Republic, any community one wishes to help is a “complex adaptive system.” Like a forest floor or coral reef, communities are ecosystems balanced on the “aggregate adaptations” built from their unique histories, cultures, and ways of life. Adding a non-native innovation or service that seeks to interrupt those relationships can have consequences that are far too complicated to predict with any accuracy.

When it comes to trying to predict or intercept those consequences, social designers face many pitfalls that can lead to miscalculations. In this article, we’ll focus on two: First, why empathy without understanding biases the best of intentions, and second, why overemphasizing an innovative solution in place of long-term, productive change leads to wasted efforts.

Against empathy (without understanding)

When most people think of empathy, they think of emotional empathy. That is your capacity to feel the emotions of another and believe you understand their emotional experiences. It’s one of three types of empathy — the others being cognitive and empathic concern — and while it seems like a for a social designer to find their North Star, it sends their moral compasses into disarray.

According to Paul Bloom, psychologist and the author of Against Empathy, emotional empathy’s downfall is that it’s biased. We extend it most often to the people who look, speak, and think as we do. And while we may imagine that we’re on the same wavelength as someone else, our empathic simulation can’t help but be colored by our own life experiences and understandings.

That bias bleeds into the social design process, where it can blind nonprofits, philanthropists, and innovators to the omissions, misunderstandings, and potential harms of their plans. For this reason, while empathy can certainly rouse sentiment, it can also be a major deterrent to holistic social change.

As Tim Brown, the executive chair of IDEO and design-thinking advocate, writes for the Stanford Social Innovation Review: “Time and again, initiatives falter because they are not based on the client’s or customer’s needs and have never been prototyped to solicit feedback. Even when people do go into the field, they may enter with preconceived notions of what the needs and solutions are. This flawed approach remains the norm in both the business and social sectors.”

PlayPump’s story shows why social designers must heed this warning. Its crusade to bring clean drinking water to underprivileged communities is laudable; the idea that so many suffer without it is viscerally motivating. However, its designers and supporters didn’t make the effort to understand the people and cultures they were trying to help.

According to a UNICEF report, in some communities, children weren’t able or willing to play on the merry-go-round. This left women to turn the wheel in an all-too-public display they found embarrassing. At one installation site, the adults had to pay children to use the merry-go-round, effectively turning the “play” selling point into child labor. Meanwhile, other communities continued to shell out fees and dues to their local water committees despite the technology being provided for free.

These and other instances demonstrated, as the report put it, “inadequate community consultation and sensitization.”

To avoid a similar mistake, Bloom recommends substituting empathy for “rational compassion.” Compassion awakens us to the need for social change through caring. But compassion must be balanced by equal parts rationality — which helps us pursue ends that reach our goals through reason and empirical evaluation.

“If I’m going to help somebody, I have to know what’s the best way to help them. Sometimes, what may seem to be the best way to help them simply makes things worse. Sometimes figuring out what to do to make the world a better place is an extraordinarily difficult task, too big for one brain, and we do our best when, as communities, we work together to think about that,” Bloom said in an interview.

Innovation as a process (not a solution)

The next miscalculation is to overemphasize an innovative solution as the end goal. PlayPump offers the pertinent lesson once again.

It tried to force a single solution (read: a social product) onto what was popularly perceived as a uniform issue. But Africa’s impoverished communities don’t face a water problem; they face many unique water problems.

For many of these communities, noted the Columbia Water Center, the challenge was not water infrastructure but water scarcity. Without enough water available to meet demand, the device was simply a more complicated rendition of the same problem. The same was true for communities with an abundance of non-potable water.

Even where the groundwater was potable, PlayPump’s design couldn’t meet the demand. By one estimate, children would have needed to operate the merry-go-round non-stop for 27 hours to meet the goal of 15 liters of water per person per day.

“The failure of PlayPump points to a huge problem in meeting water challenges — simply put, there is no panacea. Water problems are very complex and come in a multitude of flavors,” Daniel Stellar wrote for State of the Planet, the Columbia Water Center’s news site.

To avoid this miscalculation, Christian Seelos, director of the Global Innovation Impact Lab at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civility Society, and Johana Mair, professor of organization, strategy, and leadership, contend that the ideology of innovation needs to shift. Instead of praising outcomes, we must learn to favor processes — a transition that they cite “might be less glamorous but will be more productive.”

They point to the example of Aravind Eye Care Hospital, which was founded as an 11-bed hospital in Madurai, India, in 1976. The hospital was founded to “eliminate needless blindness” and centered its efforts on a chief intervention: cataract surgery.

Rather than look for a panacea cure, its administrators focused on standardization, establishing real-time performance measures, and continuously improving. By maintaining that focus, the hospital managed to expand its services and outreach while also keeping costs low enough to offer free treatment for its poorest patients.

“Aravind’s example underscores that relentless attention to incremental improvements lies at the core of an organization’s ability to build capacity and to make an impact on a scale appropriate to the social problem being addressed. Unpredictable innovation activities always compete with predictable core routines for scarce organizational resources, such as staff time and money,” Seelos and Mair conclude.

They add: “The example of Aravind also underscores that many poverty-related and persistent problems may not need innovative solutions but rather require committed long-term engagement that enables steady and less risky progress.”

Social design is about a purpose (not a panacea)

Unfortunately, when it comes to gaining attention, stirring enthusiasm, and meeting funding goals, small, specialty solutions lack the appeal of grand schemes that promise to end a problem. And that’s understandable. With so much suffering, it makes sense that we’d want to solve as many problems as quickly as possible.

However, if the goal is truly improving lives, moving the dial slowly should not be discounted, especially if that change is real, sustainable, and builds momentum toward future advances.

Surprisingly, PlayPump again perfectly illustrates this lesson. Today, the nonprofit Roundabout Water Solutions continues to install devices. However, having learned the lessons of the past, they now promote it as a “niche solution to the problem of providing clean drinking water.” They’ve found the design works best when installed at primary schools in specific communities.

“It’s the real understanding of a purpose that creates energy, and that aligns everyone around the same goal, and that provides enough of a magnet towards this North Star that people can pivot as necessary and experiment as necessary in how to get there,” Heller said in her interview.

She added that often the people who make the biggest change aren’t the ones who take the title of designer. “They are people who have an instinct to collaborate, an instinct to experiment, an instinct for establishing a purpose that is unreasonable and has social value as well as financial value as an aim, to become change agents and facilitate creative innovation in other people.”

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Cheryl Heller’s full class for your organization, request a demo.