Time is money? No, time is far more valuable. Here’s how to spend money to optimize your time

- People often say, “Time is money,” but what the aphorism misses is that time is by far the more precious resource.

- A money-centric mindset can be detrimental to your happiness compared to a time-valuing one.

- To be more “time-affluent,” clarify your core values and use your money to facilitate the pursuits and experiences that support them.

Four thousand weeks is the average lifespan of a person living in the modern world. With exercise and healthy living, you may push that number out a couple of months. Then again a disease or accident may just as easily cut it short. Give or take, 4,000 weeks is all the time you have to build the life you want.

Admittedly, such framing is stark, but it’s something we all understand on a gut level: Our time is limited, and that makes it the most precious resource we have. Yet when it comes to how we use our time, it’s often in service of money.

We spend more hours on paid work per day than any other activity except sleep — enough to subtract more than 500 weeks from a person’s 4,000. And that figure only accounts for the earning of money. When you factor in budgeting, spending, investing, and fretting over finances, then money even devours time allotted for unpaid work or “leisure” activities.

All the while, our lives tick silently away.

Of course, money is necessary. You need it to buy food, pay bills, prepare for retirement, and perform a litany of other daily to-dos. However, research suggests that once your income grows in excess of a subsistence minimum, having a money-centric mindset can be detrimental to your subjective well-being.

To build happier, more meaningful lives, you shouldn’t disburse your time in the pursuit of money; you should use your money to better facilitate your time.

Time is more scarce than money

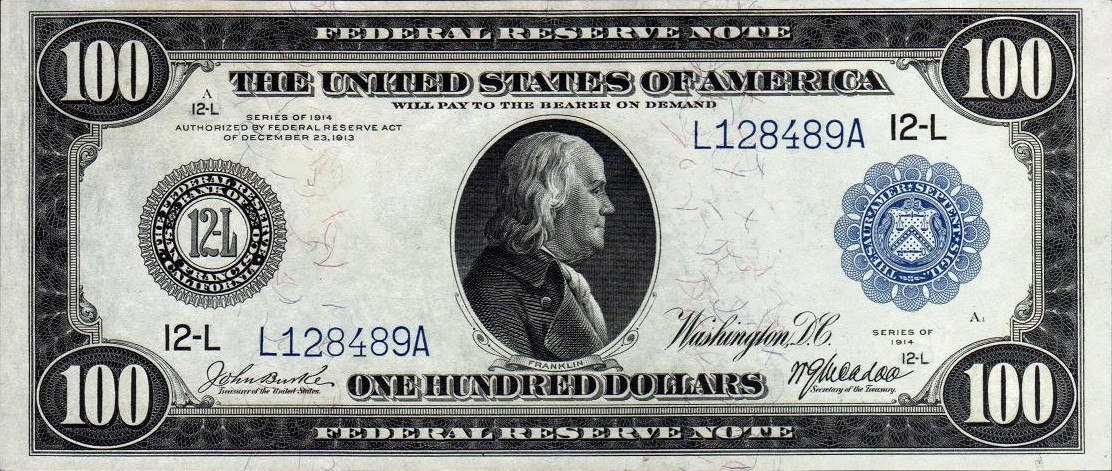

The money-centric mindset is perfectly encapsulated in the aphorism “time is money.” It’s the kind of advice that people hold in reverence not because it’s proven useful or accurate but because it has an air of extraordinary authority. This is especially true in the U.S., where it is often attributed to none other than Benjamin Franklin.

By one reading, time and money are equivalent. You spent the former to get the latter. By another, money is the best possible output of your time. Any time not spent earning money is time spent wasting it. And, of course, the entire field of finance is based on the “time value of money.”

But like so many tattered clichés, this one crumbles under scrutiny. Time and money aren’t equivalent resources. If we measure a resource’s value based on its scarcity, then time should be far more cherished because you can always increase your supply of money.

You earn more money by negotiating raises, earning promotions, or changing professions. You can sell products for more than their costs, save money to spend when it is more advantageous, or invest your money to create capital to draw from later. Heck, you can even steal it.

The same cannot be said for time. The time you spend in one pursuit can never be recovered and exchanged for something else. You cannot save your time for a more favorable season nor invest it to create more later. And while you can gain a lot from your time spent — education, health, and, yes, money — those things cannot be converted back into time.

Time is more valuable than money

For these reasons, Ashley Whillans, a behavioral scientist at Harvard Business School, argues that subjective well-being doesn’t follow from becoming rich. Instead, she recommends we aim to become “time-affluent.”

Research shows that people who value time over money enjoy greater subjective well-being. They also have better social connections, healthier family relationships, and greater job satisfaction.

And this isn’t because time-affluent people simply work less. According to one survey, they work about as much as their money-centric peers. The difference is that time-valuing participants favored “intrinsically rewarding activities,” meaning the time spent at work was more valuable to them than just a paycheck. “Nothing less than our health and happiness depends on reversing the innate notion that time is money,” Whillans writes at CNBC.

Nothing less than our health and happiness depends on reversing the innate notion that time is money.

Ashley Whillans

How to spend your money

But if we all have the same 4,000 weeks, how does anyone become time-affluent? Time cannot be earned or gained. We all have the time we have. No more, no less.

The answer is that when it comes to time, it’s not how much you have that counts. It’s how you spend it. And here, money has an important role to play. By spending your money thoughtfully, you can draw more meaning and subjective well-being from the same number of hours and weeks.

“Most people don’t know the basic scientific facts about happiness — about what brings it and what sustains it — and so they don’t know how to use their money to acquire it,” psychologists Elizabeth Dunn, Daniel Gilbert, and Timothy Wilson write in their 2011 study published in The Journal of Consumer Psychology.

They add: “Money is an opportunity for happiness, but it is an opportunity that people routinely squander because the things they think will make them happy often don’t.”

According to their research, when people think about how money can support happiness, they typically make two fundamental errors. First, their predictions are almost always off, and second, they fail to realize that the context in which they are making these predictions is not the same as the actual experience.

For example, some people might think that a new 8K TV will bring them loads of happiness. But in reality, they end up spending more money on all the hook-ups and accessories. The setup and continued maintenance take more time than they think. And while they marvel at the picture quality for a while, they quickly acclimate to the supersized pixel count. After a month, it becomes yet another TV.

So while the purchase did bring happiness, it proves significantly less than imagined, especially compared to the costs in both time and money.

Because of this, the trio notes, buying things for yourself doesn’t make you as happy or for as long as we think it will. Instead, money facilitates happiness best when we use it to buy experiences, benefit others, or indulge in small pleasures. We should not waste time comparison shopping, and we should pay attention to how our purchases can ease — rather than add to — the stresses of our daily lives. In short, rather than being money-centric, you should look at how your money and time can support your values, build relationships, and help you do the things you find meaningful. When money doesn’t manage that, then no amount of it will move the needle in either happiness or life satisfaction.

Time is money plus values

It’s one thing to say we should buy experiences and use our money to do the things we find meaningful. But it’s another to figure out which experiences and pursuits will meet that goal and shift our mindset to be more time-affluent.

According to Paula Pant, host of the Afford Anything podcast, the first step is recognizing that you cannot afford or do everything. As she said in an interview: “You just can’t have an endless series of ‘ands.’ You might not be able to have that thing and something else and something else and something else.”

After that, she recommends a first-principles exercise to clarify your core values and how they can shape your spending habits. Start by writing down the components of your life (such as family, health, career, self-worth, etc.) Then for each vertical, write down all the things you might want to accomplish by the end of your life. Remember, you have less than 4,000 weeks, so be realistic.

Then review your lists and circle the accomplishments that are most important to you. Pursuit of these should be where you focus your time, energy, and money.

“That’s a very difficult exercise because oftentimes in each of those verticals, it’s hard to pick just one, but then you’ll know what’s most important across that top horizontal span,” Pant said.

She also recommends reviewing the list to be mindful of the “core experiences” that matter to you. That’s because what looks like two values on our lists may in fact be one value. For example, you may have spending time with family and traveling the world as two separate goals. But if the people you want to travel the world with are your family, then both of those goals are connected to the core experience of relationship building.

Once you’ve budgeted enough money to pay the bills and feed the family, you should consider how you can save and spend your money to best facilitate the experiences and time you need to live those values in your life.

“And that doesn’t just apply to your money,” Pant notes. “That applies to your time, your focus, your energy, your attention — any limited resource. And life is the ultimate limited resource. So when you practice being better at managing your money, you practice being better at managing your life.”

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Paula Pant’s full class for your organization, request a demo.