If you’ve ever had the misfortune of witnessing a family member succumb to cognitive decline, then you know why Alzheimer’s disease is so terrifying.

In the early stages, there’s the occasional misplaced valuable, forgotten name, and poorly planned dinner party. Troubling but nothing extra care and attention can’t amend.

Then comes the slow and unavoidable decline. Your loved one’s mental history becomes a redacted record. Their personality bounces between bouts of worry, fear, depression, and intense anger. They begin to wander and become lost in their own neighborhoods. After several agonizing years, their mind and body deteriorate completely.

It’s a sad story and one that’s growing alarmingly prevalent. Currently, 10% of people over the age of 65 have Alzheimer’s disease. That’s close to 6 million Americans with worldwide estimates ranging as high as 24 million. By 2050, the population of Americans with Alzheimer’s is estimated to double, leading some to predict the disease will bankrupt Medicare.

How Alzheimer’s changes your brain

Thankfully, researchers have a much better understanding of how Alzheimer’s disease changes the brain than when Dr. Alois Alzheimer first recognized abnormal growths in a 1906 autopsy.

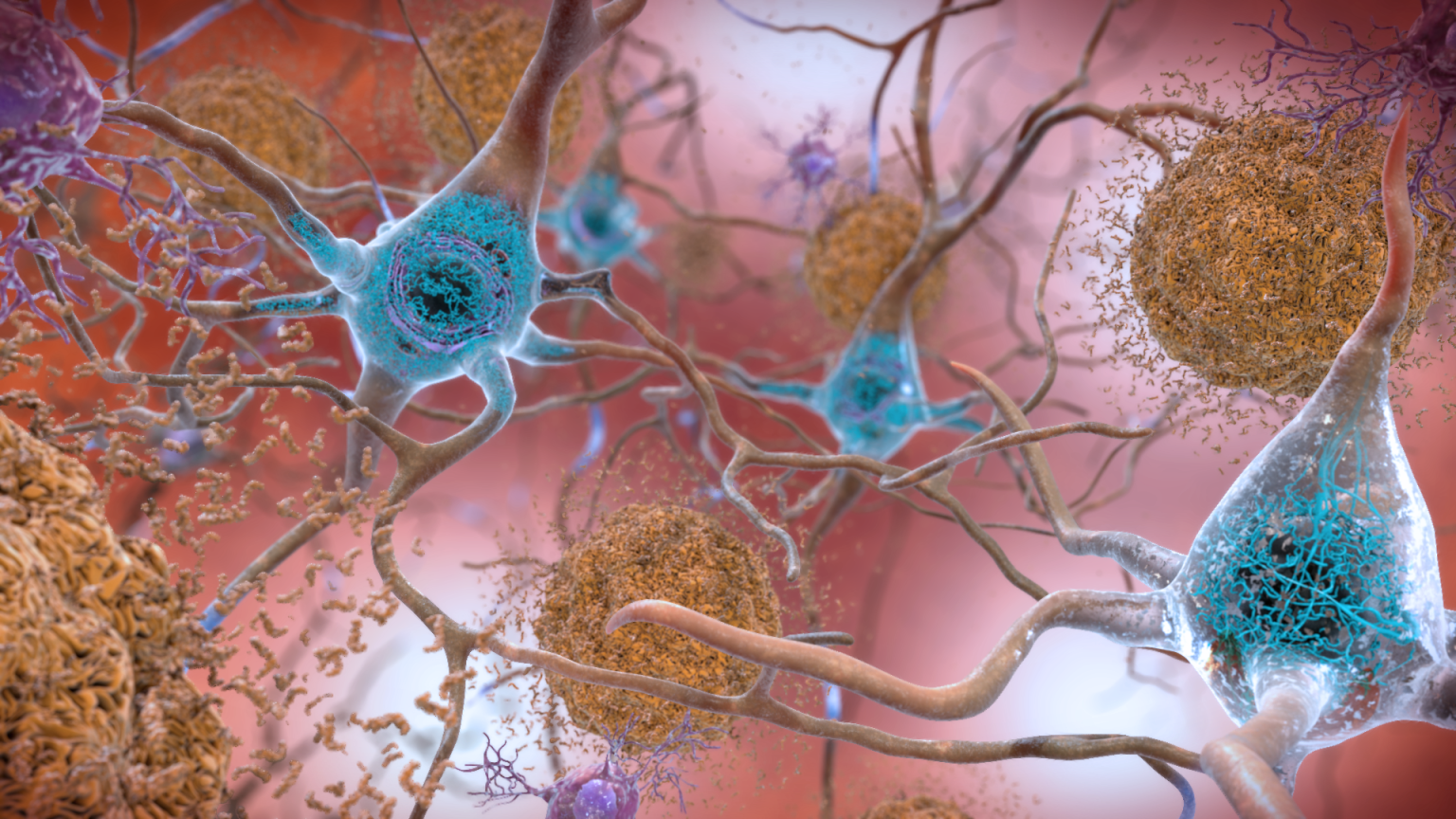

Those mysterious growths are now known to be amyloid plaques, large collections of beta-amyloid proteins. These toxic “sticky” proteins accumulate in abnormally high numbers in an Alzheimer’s-afflicted brain and are widely hypothesized to be the disease’s major driver. As they multiply and bind together, they form insoluble plaques between neurons that disrupt normal cell functions.

But amyloid plaques aren’t smoking gun pathology. Another Alzheimer’s abnormality is neurofibrillary tangles — a collection of tau proteins that form inside neurons.

Tau proteins typically serve as a building block of microtubules. They prevent microtubules from breaking apart, which in turn helps the cytoskeleton maintain the cell’s structure and shape. In a brain changed by Alzheimer’s, however, tau proteins detach from their microtubules and bind with other taus to form neurofibrillary tangles. These tangles block the synaptic communication between nerve cells, further harming normal cell functions.

Rounding out the players are neuroinflammation and vascular problems, such as reduced blood flow and an inability for glucose to pass the blood-brain barrier.

In a normal brain, microglial cells clean metabolic waste during sleep. But with the onset of Alzheimer’s, these cells become unable to perform their duties properly. The reasons for this cellular delinquency remain unknown, but the outcomes are evident. As the waste piles up — including those nasty beta-amyloid proteins — inflammation spreads throughout the brain.

Similarly, vascular problems are evidently at play in Alzheimer’s, but such problems may be a consequence or a cause of the symptoms. How they relate to the Alzheimer’s cycle remains difficult to suss out.

The tipping point

It seems as though amyloid plaques precede the other Alzheimer’s symptoms, but they alone aren’t enough to develop the disease. According to neuroscientist and author Lisa Genova, there’s a tipping point of plaque build-up that ultimately kicks things off.

“It’s sort of like if you have high cholesterol,” she said in an interview. “It doesn’t mean you’re going to have a heart attack. So below the tipping point, your symptoms of forgetting are all normal.”

In other words, your brain is functioning fine. There’s no need to freak out every time you misplace your keys or recall needing bread 10 minutes after you’ve left the store. But beyond that tipping point is a surge of neurofibrillary tangles, neuroinflammation, vascular problems, and cell death. The “glitches in memory formation and retrieval” now take on a different tenor.

“Things that you would normally remember from last week won’t get consolidated because your hippocampus is under attack,” Genova said.

The attack doesn’t stop at the hippocampus either. As Alzheimer’s develops from early to moderate stages, plaques, tangles, and inflammation spread throughout the brain. This explains the classic cognitive decline from memory loss to difficulties with speech, problem-solving, and personality.

In time, this progression leads to brain atrophy and death.

A stymied search for a cure

While researchers know how Alzheimer’s disease changes the brain, they still don’t know what causes it. What combination of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors initiates things? How do the symptoms interplay, triggering and exacerbating each other? The lack of answers to these questions has kept effective cures and treatments out of reach for decades.

“It doesn’t seem that there’s one single superstar mechanism that is the magic solution,” Dr. Vijay Ramanan, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, told NBC. “It’s an all-hands-on-deck kind of situation with research to try to identify better diagnosis and treatment options.”

For example, the amyloid cascade hypothesis has led many researchers to focus their efforts on beta-amyloids and their plaques. Unfortunately, a succession of failed clinical trials and some high-profile data mismanagement has left those efforts frayed.

The first amyloid treatment to be green lit by U.S. regulators in nearly 20 years, aducanumab, has met with controversy. Its critics argue the drug shows little evidence of benefiting patients and risks serious side effects such as brain swelling. In fact, an independent committee rejected the treatment after reviewing its clinical trial data, and three of its advisors resigned in protest after the FDA approved it anyway.

Facing this stymied progress, some researchers are now looking beyond amyloids for new hypotheses while others are turning toward non-amyloid-focused treatments.

One such treatment — the awkwardly named T3D-959 — was presented at the 2022 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference. It aims to help Alzheimer’s brains overcome their insulin resistance to restore metabolic health. (Alzheimer’s disease is sometimes referred to as “type-3 diabetes” because patients with type-2 diabetes have an increased risk of developing dementia later in life. However, this characterization is not widely accepted in the medical community.)

“We will most likely need to combine multiple treatments that address the disease in different ways for effective treatment and prevention,” the Alzheimer’s Association said in a statement.

How to build an Alzheimer’s-resistant brain

The lack of effective treatments is disquieting, but Alzheimer’s research has led to some promising discoveries. Namely, we aren’t as powerless as we may think.

“For the vast majority of us, Alzheimer’s is not our brain’s destiny,” Genova said. “Only 2% of folks have Alzheimer’s that is 100% inherited. [And the] accumulation of amyloid plaques takes 15 to 20 years and can be influenced by how we live.”

While there’s no proven Alzheimer’s prevention method, a strong connection does exist between certain lifestyle choices and a reduced risk of developing the disease. Genova points to five:

Get good sleep

By getting the proper amount of sleep, you give your microglial cells the time they need to clean your brain properly. That means 7–9 hours on average for an adult. Without that sleep, uncleared metabolic waste will continue to build up over the years. And, of course, you’ll suffer daily quality of life problems, too.

Exercise regularly

“A brisk walk for 30 minutes, four to five times a week is enough to decrease your amyloid plaque levels and reduce your risk of developing Alzheimer’s by a third to a half,” Genova said. “If I offered you a pill that would reduce your risk of Alzheimer’s by 50%, you’d take it.”

Exercise can also benefit people who already have Alzheimer’s disease. A randomized controlled trial out of Finland found that while all Alzheimer’s patients continued to deteriorate cognitively, those placed in the control group did so “significantly faster” than those assigned to exercise groups.

Its writers concluded: “An intensive and long-term exercise program had beneficial effects on the physical functioning of patients with [Alzheimer’s disease] without increasing the total costs of health and social services or causing any significant adverse effects.” (Medicare, take note.)

Maintain a healthy diet

A healthy diet supplies brain health. Which diet is best? That depends a lot on you and your specific needs. The best person to consult here is your doctor.

With that said, studies have shown the Mediterranean diet to be associated with a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease. So enjoy plenty of nuts, fruits, veg, legumes, cereals, and olive oil; some eggs, fish, dairy, and lean poultry; as well as the occasional glass of wine.

Maintain healthy stress

Chronic stress has been shown to affect the hippocampus in numerous ways. So maintaining low levels of stress — whether through mindfulness, exercise, an active social life, or just taking it easy — can help you maintain an Alzheimer’s-resistant brain.

As a bonus, studies have shown that anxiety degrades people’s performance on a variety of memory tests. So maintaining low-stress levels can benefit anyone.

Learn new things

“If you’ve lived a life where you’re cognitively active, you’re regularly learning new things; you are building what we call a ‘cognitive reserve.’ Every time you learn something new, you’re building new synapses. You’re building new neural connections.”

Given that the human brain contains an estimated 100 billion neurons and each neuron may build thousands of synapse connections, that’s a lot of potential cognitive reserves you can build in a lifetime. Thankfully, there’s a lot you can learn in a lifetime, too.

The cumulative effects of good health

Other things you can do to improve your chances of skirting cognitive decline include drinking in moderation, giving up smoking, and staying socially active with loved ones and within your community.

If this list seems oddly familiar, that’s because it should be. It’s the same advice healthcare professionals provide to help people improve cardiovascular health, reduce their risk of diabetes, prevent strokes, fortify their mental health, and generally live a happy, long, and fulfilling life.

That’s because, as a 2020 CDC study found, people with chronic conditions also show an increased prevalence of subjective cognitive decline. Your body and brain create an interconnected system. The healthy habits you develop for one support the other.

“A lot of these lifestyle factors work as well as any pill that we might develop for preventing Alzheimer’s,” Genova concluded. “We just have to do them.”

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Lisa Genova’s full class for your organization, request a demo.