Male body ideals have changed strikingly. While men have always aimed to be muscular, the past two decades have witnessed a gradual amplification in what qualifies as fit. Today’s idolized male body not only has well-defined shoulder, chest, and arm muscles; it also sports low body fat, a chiseled six-pack, and glutes shaped to callipygian perfection.

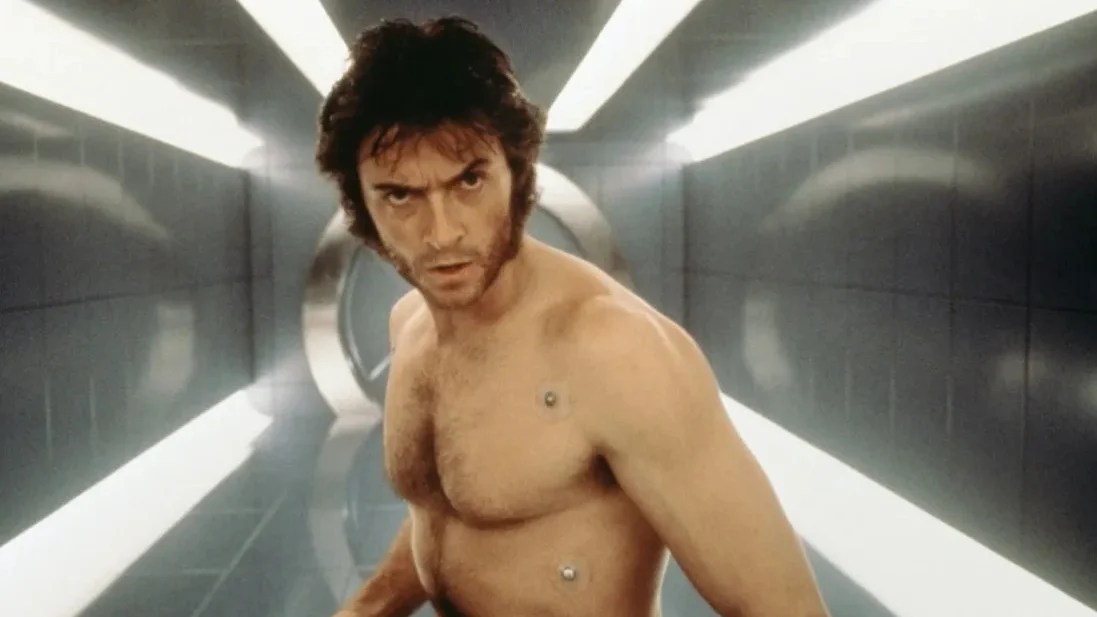

As pointed out by health writer Sarah Berry, this muscle creep is evident in America’s icon of masculinity: the superhero film. When actor Hugh Jackman first played the character of Wolverine in X-Men (2000), he embodied the fitness and “muscularity” of the day. Then the shredded Spartans of 300 (2006) kick-started a literal arms race leading to increasingly swole physiques among heroes such as Thor, Superman, and Blank Panther. Even Jackman’s original Wolverine looks “nothing short of doughy” compared to his most recent performances in the role.

“The bodies of boys, men and the heroes they aspire to look like have changed,” Berry writes for The Sydney Morning Herald. “It is twisting the perception many have of what is normal and what people are willing to do to achieve it.”

That twisted perception has accelerated across social media, too. The lifestyle influencers of TikTok and Instagram preach that muscularity is attainable to anyone with the fortitude and strength of character to obtain it. For example, Brain Johnson — doing business as the Liver King — claims such a physique can be had by following ten “ancestral tenets.” His message reaches millions of followers daily, and he is just one muscular mountebank hawking his wares on social media. (Johnson also sells “ancestral supplements” online — just like our hunting-and-gathering forefathers used to.)

And these messages are having an ill effect on young men’s body esteem. In fact, research suggests that the more time adolescents and young men spend on social media, the more likely they are to develop a poor body image.

Social media and boys’ body image issues

A recent study published in Eating and Weight Disorders looked at the relationship between screen use and the symptoms of muscle dysmorphia — a type of body dysmorphic disorder in which someone believes themselves to be weak even if they are fit and healthy. Muscle dysmorphia leads to compulsive workout routines and rigorous dieting. Behaviors may also include constant mirror-checking, avoiding public exposure, an always shifting goal post of bodily acceptance, and, in some cases, using anabolic steroids.

To explore the connection, the researchers analyzed data from the Canadian Study of Adolescent Health Behaviors on screen use and body image. Screen time consisted of social media use as well as texting, watching TV, video chatting, playing video games, and watching online videos. Body images were assessed using the Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory.

The researchers found that muscle dysmorphia symptoms were associated with increased screen time. Among young men specifically, greater time texting and on social media correlated with greater symptoms. Among young women, it was time spent texting, video chatting, and watching videos.

“Our data support the notion that various forms of screen use may be contributing to muscle dysmorphia risk factors, including body dissatisfaction and pressures to achieve sociocultural body ideals,” Kyle Ganson, the study’s lead author and an assistant professor at the University of Toronot’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, said in a press release.

He added: “Parents, health care providers, and public health professionals should be thinking about how we can limit and promote safe use of screens for young people in hopes of reducing symptoms of mental health, including those of muscle dysmorphia.”

Does screen time fuel poor body esteem?

Despite the association between social media and muscle dysmorphia in young men, it’s not clear which way the causal arrow points. Do preexisting body image issues lead young men to seek solutions on social media? Or does the online parade of idealized physiques lead young men to disparage their own bodies? Researchers simply don’t know — and, of course, it could result from many different causes. However, they are starting to do preliminary work to discover social media’s role.

A pilot study published in the Psychology of Popular Media ran a four-week randomized controlled trial with 220 young-adult participants. The participants were between the ages of 17 to 25 years old, regular social media users, and exhibited symptoms of depression or anxiety. The researchers tracked the participants’ social media use for one week to create a baseline and then randomly assigned them to either a control or intervention group. Participants in the control group continued using social media as normal; meanwhile, participants in the intervention group were asked to limit their usage to one hour per day. Body esteem surveys were taken at the beginning and end of the trial.

While the researchers did not look at muscle dysmorphia specifically, they did find that participants in the intervention group felt more favorably about their appearance and weight after the three weeks. Meanwhile, the control group saw no significant change. These results suggest that heavy social media use does influence body image.

“Social media can expose users to hundreds or even thousands of images and photos every day, including those of celebrities and fashion or fitness models, which we know leads to an internalization of beauty ideals that are unattainable for almost everyone, resulting in greater dissatisfaction with body weight and shape,” Gary Goldfield, the study’s lead author, said in a release.

Of course, as a pilot study, its design does house some limitations. Its small sample size means we can’t generalize to the population nor draw inferences around gender. Similarly, its short duration means the intervention’s long-term effects can’t be analyzed. However, the results were promising, and the researchers are looking into further research.

“Reducing social media use is a feasible method of producing a short-term positive effect on body image among a vulnerable population of users and should be evaluated as a potential component in the treatment of body-image-related disturbances,” Goldfield added.

It’s okay to not be super

What can we learn from the research? First, the research linking social media with body esteem issues in young men and women is still immature. There’s a lot we don’t know because widespread social media use is a relatively new cultural phenomenon. Second, it’s difficult for researchers to suss out social media’s influence from other potential causes such as bullying, feelings of loneliness, and issues at home. Then there’s the rub that some personality types may simply be more susceptible to social media’s negative elements.

With that said, the data are trending in meaningful directions. While the influence social media plays in body image issues is unknown, it does appear to play a role, especially among young adults who spend a lot of time online. Research suggests that greater time spent on screens and social media is associated with depression, anxiety, and eating disorders, as well.

None of which is to say that social media can’t be a healthy, useful, and enjoyable part of a young person’s life. Just that, as in so many things, healthy limits are important.

Another direction is that while we traditionally view body esteem as a challenge for young women — and it certainly is — young men are just as likely to struggle with accepting their bodies among the onslaught of social pressures and idealized images of the male body.

“Increasingly, masculinity in modern culture represents not what you do, but how you look. So, the value that society has placed on being muscular may explain why muscle dysmorphia is more common in men,” Ieuan Cranswick, senior lecturer in sport and exercise therapy at Leeds Beckett University, writes for The Conversation. (Though again, “more common” should not be read as “exclusive to.”)

How can parents help? If your child is young enough to still live with you, start by working with them to set healthy limits on screen time. In lieu of an authoritative ultimatum, include your child in the conversation, help them understand the reason for the boundary, and, at the same time, be sure to understand where they are coming from.

“What I would say in general is that I think kids need boundaries, and they need to know that their parent is a sturdy pilot during turbulent times — which is a lot of childhood. They also need to feel seen and validated. I think kids are always asking two questions of parents: Am I safe, and am I real?” Becky Kennedy, clinical psychologist and parent expert, said in an interview.

Parents should also help their children develop social media literacy. Learn with your child how to think critically about the claims and information found online. Teach them how online messages are shaped to embed worldviews, commercial implications, and perceptions of worth that aren’t necessarily crafted for their benefit.

Returning to the Liver King, he created an online persona and message designed to sell supplements — not to improve lives and people’s well-being. And his message was misleading on many fronts: Our ancestors ate nothing like his prescribed diet, and Johnson himself was on a cocktail of steroids and growth hormones to build his so-called “primal” physique.

Understanding the artificiality that goes into entertainment and selling such ideas — as well as the stories of others who have recovered from low body esteem — can help develop that literacy.

If you’re worried your child may have body dysmorphia or another body-image disorder, seek professional help. A psychiatrist or psychotherapist can help not only diagnose the issue but provide you and your child with the tools to begin making a change. If you don’t know where to begin, consider checking out the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Foundation’s website.

Finally, be open with your child. Talk with him or her, and listen without shame or stigma. Offer support and be there when they need you. Create a loving and supportive environment that values them for who they are and the skills they’ve developed, not how they look. Even in the case of physical exercise, emphasize performance and improvement over physique.

One advantage you have as a parent is that you can connect with your child in ways that are far more solid, real, and lasting than any fantasy sold online.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.