The Turing test: AI still hasn’t passed the “imitation game”

- In 1950, the British mathematician and cryptanalyst Alan Turing published a paper outlining a provocative thought experiment.

- The so-called Turing test is a three-person game in which a computer uses written communication to try to fool a human interrogator into thinking that it’s another person.

- Despite major advances in artificial intelligence, no computer has ever passed the Turing test.

Can machines think? That was the question Alan Turing posed at the top of his landmark 1950 paper, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” The paper was published seven years after the British mathematician had cemented his place in history by decrypting the German Enigma machine during World War II. It was a time when rudimentary electronic computers were just starting to emerge and the concept of artificial intelligence was almost entirely theoretical.

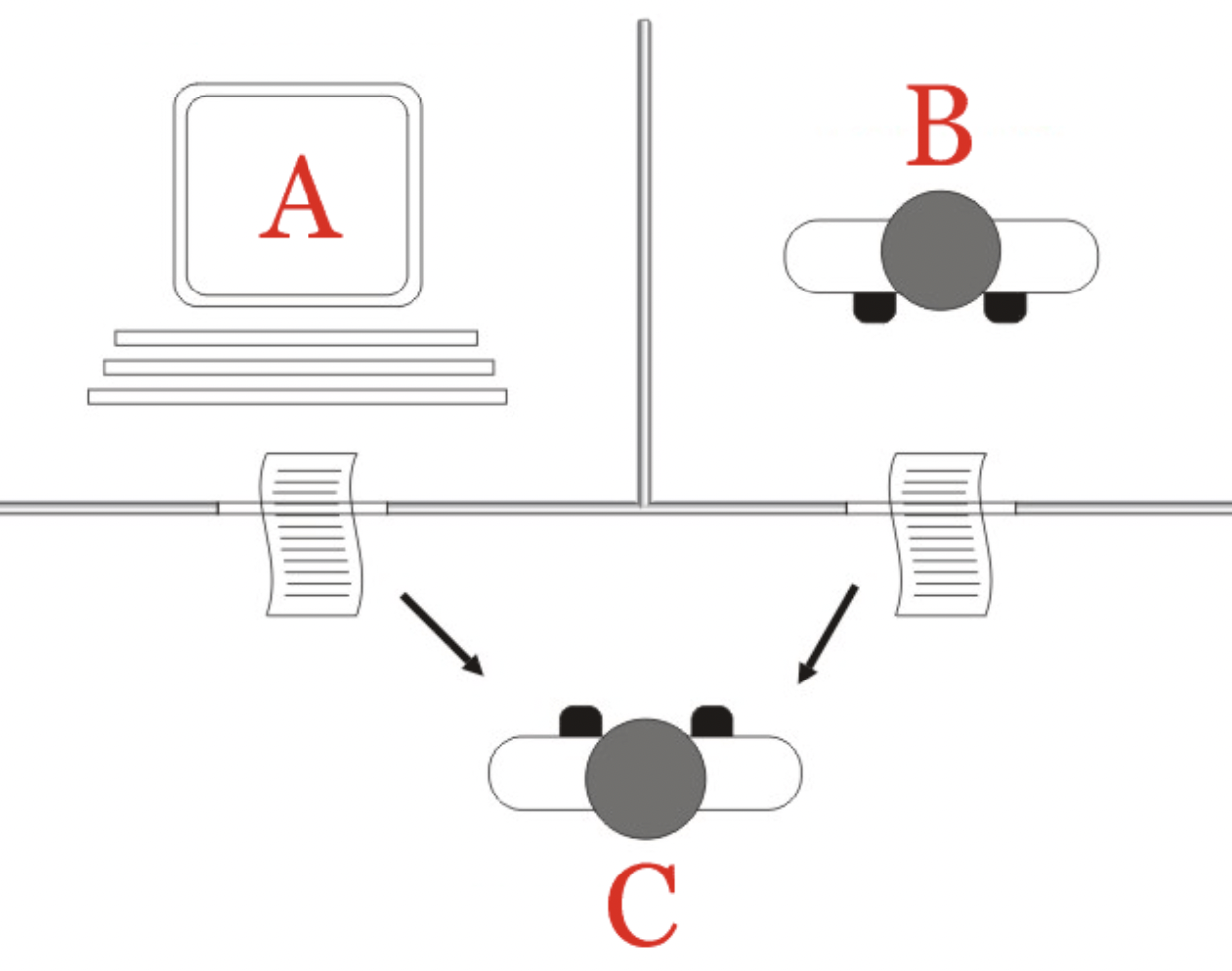

So, Turing could only explore his inquiry with a thought experiment: the imitation game. The game, commonly called the Turing test, is simple. One person, player C, plays the role of an interrogator who poses written questions to players A and B who are in a different room. Of A and B, one is human and the other is a computer.

The object is for the interrogator to determine which player is the computer. He can only try to infer which is which by asking the players questions and evaluating the “humanness” of their written responses. If the computer “fools” the interrogator into thinking its responses were generated by a human, it passes the Turing test.

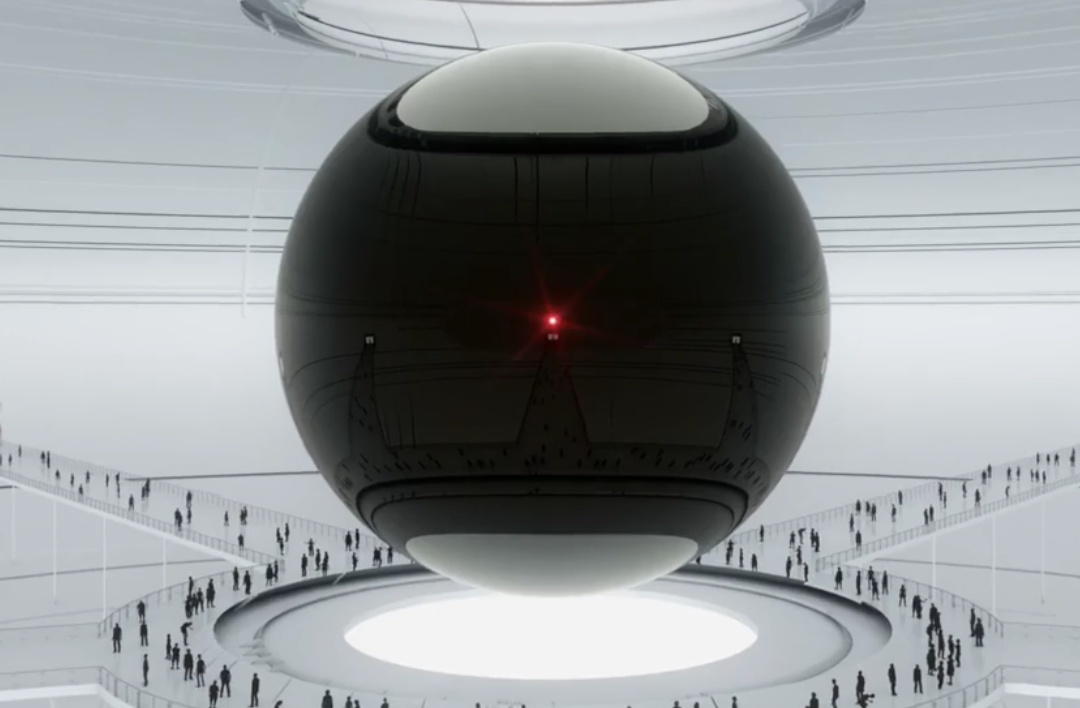

The test was not designed to determine whether a computer can intelligently or consciously “think.” After all, it might be fundamentally impossible to know what’s happening in the “mind” of a computer, and even if computers do think, the process might be fundamentally different from the human brain.

That’s why Turing replaced his original question with one we can answer: “Are there imaginable computers which would do well in the imitation game?” This question established a measurable standard for assessing the sophistication of computers — a challenge that’s inspired computer scientists and AI researchers over the past seven decades.

The new question was also a clever way of sidestepping the philosophical questions associated with defining words like “intelligence” and “think,” as Michael Wooldridge, a professor of computer science and head of the Department of Computer Science at the University of Oxford, told Big Think:

“Turing’s genius was this. He said, ‘Well, look, imagine after a reasonable amount of time, you just can’t tell whether it’s a person or a machine on the other end. If a machine can fool you into not being able to tell that it’s a machine, then stop arguing about whether it’s really intelligent because it’s doing something indistinguishable. You can’t tell the difference. So you may as well accept that it’s doing something which is intelligent.’”

Computers try to beat the Turing test

To date, no computer has decidedly passed the Turing AI test. But there have been some convincing contenders. In 1966, the computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum developed a chatbot called ELIZA that was programmed to search for keywords in the interrogators’ questions and use them to issue relevant responses. If the question contained no keywords, the bot repeated the question or gave a generic response.

ELIZA, along with a similar 1972 chatbot that modeled schizophrenic speech patterns, did manage to fool some human interrogators. Does that qualify them as winners? Not necessarily. Turing tests are highly debated among computer scientists, in part because of the ambiguity of the rules and the varying designs of the tests. For example, some tests have been criticized for using “unsophisticated” interrogators, while other tests have used interrogators who were unaware of the possibility that they might be talking to a computer.

Official winners or not, some recent computers in Turing competitions are pretty convincing. In 2014, for example, a computer algorithm successfully convinced one-third of human judges at the UK’s Royal Society that it was human. But there was a catch: The algorithm, dubbed Eugene Goostman, claimed to be a 13-year-old boy from Ukraine; it’s probably easier for an algorithm to fool judges when its backstory allows for broken English and an immature worldview.

Here’s a brief excerpt from one conversation with Goostman:

- [15:46:05] Judge: My favourite music is contemporary Jazz, what do you prefer?

- [15:46:14] Eugene: To be short I’ll only say that I HATE Britnie [sic] Spears. All other music is OK compared to her.

- [15:47:06] Judge: do you like to play any musical instruments

- [15:47:23] Eugene: I’m tone deaf, but my guinea pig likes to squeal Beethoven’s Ode to Joy every morning. I suspect our neighbors want to cut his throat … Could you tell me about your job, by the way?

In 2018, Google CEO Sundar Pichai unveiled an informal Turing test when he published a video of the company’s virtual assistant, called Duplex, calling a hair salon and successfully booking an appointment.

The woman who answered the phone seemed to have no idea she was talking to a computer. (Axios has suggested that the publicity stunt may have been staged, but it’s easy enough to imagine that a modern virtual assistant could fool someone who is unaware a Turing test is taking place.)

Turing AI: Artificial general intelligence

In the 1950s, the Turing test was a provocative thought experiment that helped spark research in the nascent field of AI. But despite the fact that no computer has beaten the test, the imitation game feels a bit more outdated and irrelevant than it probably did 70 years ago.

After all, our smartphones pack more than 100,000 times the computing power of Apollo 11, while modern computers are able to crack codes like Enigma almost instantly, beat humans in chess and Go, and even generate slightly coherent movie scripts.

In the book Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, the computer scientists Stuart J. Russell and Peter Norvig suggested that AI researcher should focus on developing more useful applications, writing “Aeronautical engineering texts do not define the goal of their field as ‘making machines that fly so exactly like pigeons that they can fool other pigeons.'”

What are those more useful applications? The grand goal of the field is to develop artificial general intelligence (AGI) — a computer capable of understanding and learning about the world in the same way as, or better than, a human being. It is unclear when or if that will happen. In his 2018 book Architects of Intelligence, the futurist Martin Ford asked 23 leading AI experts to predict when AGI will emerge. Of the 18 responses he received, the average answer was by 2099.

It is also unclear when AI will conclusively conquer the Turing test. But if it does occur, it is sure to precede the development of AGI.

This article was originally published in October 2021. It was updated in March 2022.