New space plane would fly directly into orbit from a runway

- Space planes are vehicles that can fly horizontally in Earth’s atmosphere, like airplanes, but can also enter space.

- No one has built such a spacecraft before.

- If successful, space planes could drastically reduce the cost of spaceflight.

This article was originally published on our sister site, Freethink, and is an installment of Future Explored, a weekly guide to world-changing technology. You can get stories like this one straight to your inbox every Thursday morning by subscribing here.

One of the “holy grails” of spaceflight could hit the skies this decade.

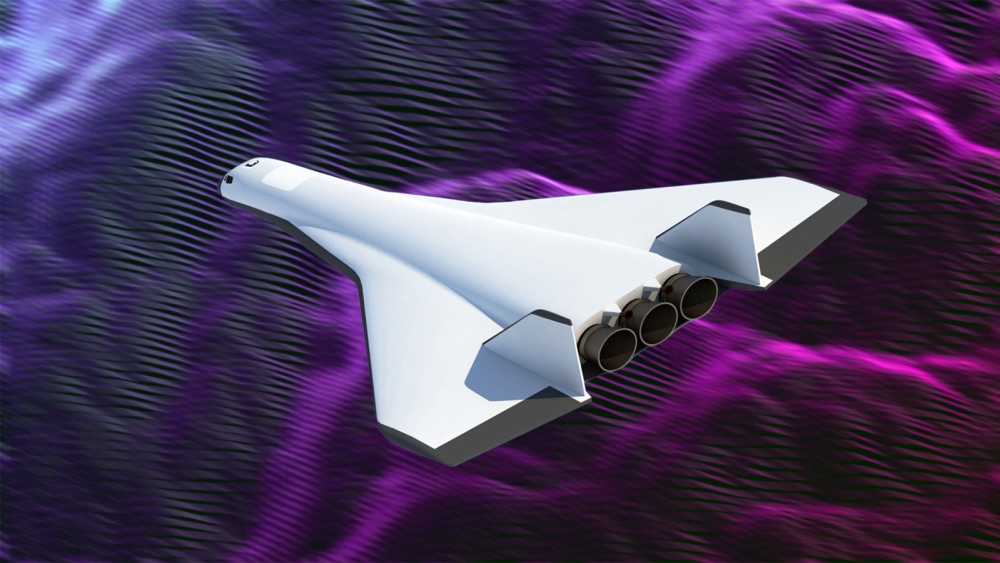

On January 19, Washington-based startup Radian Aerospace came out of stealth mode, announcing that it had secured $27.5 million in funding to develop the Radian One, a first-of-its-kind space plane that flies into orbit after taking off horizontally from the ground.

Why it matters: No one has built such a spacecraft before, and if Radian can pull it off, it’d likely cut the cost of spaceflight significantly, enabling new opportunities for off-world research, manufacturing, exploration, and more.

“We believe that widespread access to space means limitless opportunities for humankind,” Richard Humphrey, Radian’s CEO and co-founder, said. “Over time, we intend to make space travel nearly as simple and convenient as airliner travel.”

Space planes 101: Space planes are pretty much what you’d expect from the name: vehicles that can fly horizontally in Earth’s atmosphere, like airplanes, but can also enter space.

They’re reusable, like some rockets and spaceships, but unlike those craft, space planes can land anywhere there’s a standard commercial airplane runway — no need to target deserts, ships, landing pads, or oceans.

“Over time, we intend to make space travel nearly as simple and convenient as airliner travel.”

RICHARD HUMPHREY

Only three space planes have ever successfully flown: NASA’s Space Shuttle, Boeing’s X-37B, and the Soviet Buran. But all three launched vertically, attached to rockets that detached and fell back to Earth after getting the space planes into orbit.

This approach — two-stage-to-orbit — means the space planes themselves can be smaller and lighter, since they don’t need to include all the engines and fuel tanks necessary to reach space.

However, it also means more fuel is needed for launch as the first stage rockets have to lift the space planes and themselves high above Earth’s surface — and that extra fuel adds to the per-flight cost.

Radian One: No one has successfully launched a single-stage orbital space plane — yet. That’s the goal for Radian One, which is designed to accommodate a crew of five people and up to 5,000 pounds of cargo.

Radian’s plan is to launch the space plane horizontally on top of a rocket-powered sled. The sled will accelerate down a runway before Radian One detaches and takes off — this approach should help it pick up speed without expending any of the fuel stashed onboard.

Radian aims to have its space plane ready to fly again within 48 hours of landing.

Radian One will then complete a low-g ascent into space under the power of its three onboard engines. After completing its mission, which could last up to five days, the space plane will land horizontally on a runway like an airplane.

The company aims to refurbish it and make it ready to fly again within 48 hours.

“Radian is doing what’s known as the ‘holy grail’ of accessing space with full reusability and responsiveness to provide customers unmatched cost effectiveness and flexibility,” said Doug Greenlaw, a Radian investor and advisor who was formerly a chief executive at Lockheed Martin.

Looking ahead: It’s too soon to say whether Radian’s space plane will take off, but the company does have stellar credentials — its co-founders hail from Boeing, NASA, the U.S. Department of Defense, and beyond, while its advisory board includes former International Space Station (ISS) and Space Shuttle commanders.

Humphrey told Ars Technica that the company has already made some progress on its space plane, too, building and testing a full-size engine for it.

“We’re still in the leading edges of that work,” he said. “We understand the fundamentals, we can start it, we can stop it, and we’re taking a series of small, progressive steps to get to a full capability.”

“We are dedicated to missions that make life better on our own planet, like in-space manufacturing and terrestrial observation.”

RICHARD HUMPHREY

A lot more work (and a lot more money) will be needed to get the Radian One off the ground, but Humphrey said the goal is to have the vehicle operational well before 2030 for missions that aren’t solely about off-world entertainment.

“We are not focused on tourism,” he said. “We are dedicated to missions that make life better on our own planet, like research, in-space manufacturing, and terrestrial observation, as well as critical new missions like rapid global delivery right here on Earth.”

The big picture: Regardless of whether Radian One flies, governments and the aerospace industry seem keen on space planes — even if they need multiple stages to reach orbit.

In September 2020, Chinese state media reported that an experimental reusable spacecraft had completed a successful test flight — the nation didn’t outright say it was a space plane, but a military official implied that it’s similar to the X-37B.

In March 2021, a Russian news site reported that Roscosmos, the Russian space agency, was also developing a space plane similar to the X-37B. The European Space Agency (ESA) is expected to fly its own in-development space plane, Space Rider, in 2023.

In the U.S., NASA has signed a contract with Sierra Nevada Corporation (SNC) to have the company’s two-stage space plane, Dream Chaser, make at least six cargo resupply missions to the ISS.

The first of those flights is expected to happen in 2022, without a crew, but SNC expects to have a crewed version of the Dream Chaser — designed to transport professional astronauts and space tourists — ready by 2025.

“This is a monumental step for both Dream Chaser and the future of space travel,” CEO Fatih Ozmen said in May 2021. “To have a commercial vehicle return from the International Space Station to a runway landing for the first time since NASA’s space shuttle program ended a decade ago will be a historic achievement.”