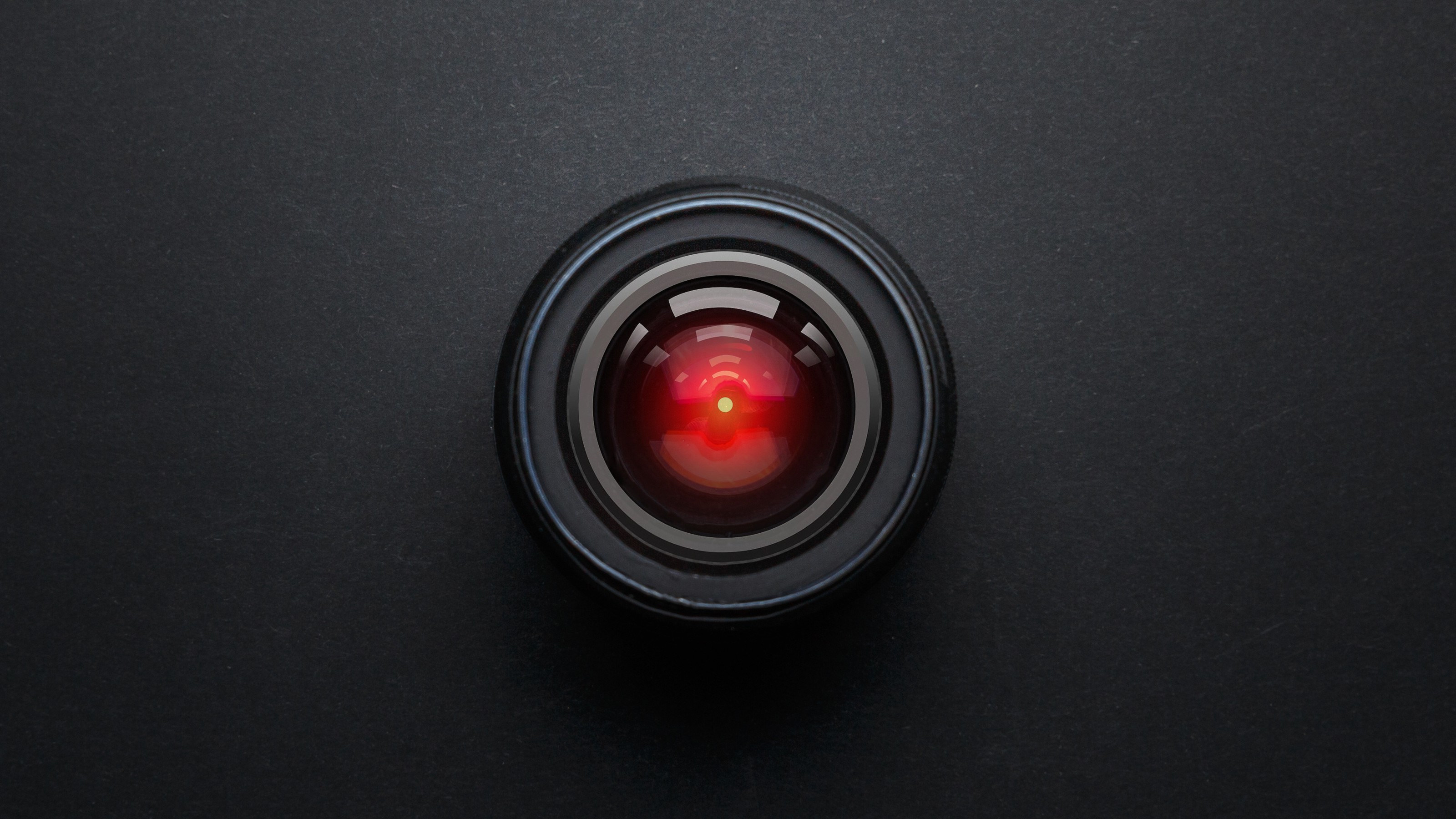

How “Big Brotherhood” is building an all-seeing surveillance network

- We expose our lives to scrutiny whenever we interact with a phone or a computer, and every time we visit a website or use an app.

- The future is a ‘big brotherhood’ of hidden, unblinking eyes, some belonging to the state but countless others belonging to private parties.

- Anxieties about being identified will eventually be superseded by concerns about being analyzed. We are not as mysterious as we like to think, even if the capability of computers is sometimes overhyped.

Excerpted from The Digital Republic: On Freedom and Democracy in the 21st Century by Jamie Susskind. Published by Pegasus Books. © Jamie Susskind. Reprinted with permission.

Imagine a huge bazaar bustling with activity. A sign by the entrance proclaims that traders come here from all over the world. Hundreds of billions of dollars change hands every year.

But this is not a normal market.

In stalls and kiosks where you’d expect to find fresh produce or homeware, only one product is for sale: people’s personal data. What they eat for breakfast, where they sleep, what they do for work, what they believe and care about, the kind of TV they watch, their ages and sexual preferences, their insecurities and fears – there is data here about hundreds of millions of people. Some merchants sell filthy buckets of raw data in need of a clean. Others offer neat packages, crisply tailored to the needs of their clientele. One vendor hawks a list of rape victims – seventy-nine bucks for a thousand – along with a list of victims of domestic abuse. There are no law-enforcement officials in sight.

This data market actually exists but is, of course, too large for any single physical space. It thrives, particularly in the US, because there is an abundance of supply and a great deal of demand. The world is increasingly reflected in data. Satellites capture the entire planet every day at a resolution so fine that ‘every house, ship, car, cow, and tree on Earth is visible’. On Earth, almost every human encounter with technology leaves a trail of data that can be hoovered up and sold on. Data is inexhaustible. We generate it just by existing, and more and more of it is being captured and stored. Thousands of businesses have sprung up to trade in it. And business is good.

What happens to all this data? Usually, purchasers are not interested in the sordid details of individual lives, a fact that can get lost in debates about online privacy. Data’s real value emerges when it is gathered in gigantic amounts to build computing systems that can find patterns and predict behaviour. For these systems, each person ceases to be an individual and becomes instead a bundle of attributes – millennial, sausage dog owner, cheese addict – a ‘voodoo doll’ that can be chopped, changed and aggregated with the attributes of thousands of others. The promise of ‘big data’ is that there are correlations out there that can only be seen when thousands or millions of cases are considered together. And when those are patterns are revealed, strangers can know us in ways we might not even know ourselves. This is a form of power.

***

In the twentieth-century imagination, surveillance meant a secret agent peering unseen from behind the curtain of a darkened room. Some still cling to that image. Steven Pinker, for example, offers reassurance that we have been able to install surveillance cameras in ‘every bar and bedroom’ for a long time, but that we have not done so because ‘governments’ don’t have ‘the will and means to enforce such surveillance on obstreperous people accustomed to saying what they want’. Pinker, however, is taking comfort from a world that no longer exists. Today’s authorities don’t have to force us to place surveillance devices in our homes. And they don’t have to see us in order to watch us. We expose our lives to scrutiny whenever we interact with a phone, computer or ‘smart’ household device; every time we visit a website or use an app. And personal data usually finds its way to those who want it most. Thus, when police in the US wanted information about Black Lives Matter activists, they didn’t need to spy on them with cameras in bars. They bought what they needed in the data market. Facebook had a trove of data about users interested in Black Lives Matter, which it sold to third-party brokers, who sold it on to law-enforcement authorities. For juicy data that cannot be found on the open market, Facebook has a special portal for police to request photographs, data about advertisement clicks, applications used, friends (including deleted ones), the content of searches, deleted content and likes and pokes. Facebook provides data 88% of the times it is asked.

Even in the physically ‘private’ space of home, there is already little escape from data-gathering devices. If you used Zoom to keep in touch with your family during the Covid-19 crisis, Zoom will have sent Facebook details of where you live, when you opened the app, the model of your laptop or smartphone, and a ‘unique advertiser identifier’ allowing companies to target you with advertisements. Zoom is not even owned by Facebook. It merely used some of its software. A commercially available dataset recently revealed more than thirty devices that were using hookup or dating apps within secured areas of the Vatican city – that is, areas generally accessible only to senior members of the Catholic Church. That’s the kind of secret that would probably have stayed hidden in the past.

The future is not Big Brother, in the sense of one government monolith watching us all at once. It is, instead, a ‘big brotherhood’ of hidden, unblinking eyes, some belonging to the state but countless others belonging to private parties who watch us while remaining unseen.

Another anxiety inherited from the twentieth century is the sense that anonymity is no longer possible; that even if we try to hide, powerful others will always know exactly who we are and where to find us. In recent years, this fear has led to concern about the spread of facial recognition systems. In fact, our faces are just one way to identify and locate us. The unique identifiers in our smartphones and payment devices telegraph our presence wherever we go. Using location data from the phones of millions of people, it took minutes for journalists to track the whereabouts of the President of the United States. There are systems that can monitor people’s heartbeats and read their irises from afar. Others use WiFi technology to identify individuals through walls. With the right tech, a person’s gait can identify them as readily as a fingerprint. In the future it may be possible to ‘Google spacetime’ to find where any of us were at a specific time and date.

Taking a longer view, anxieties about being identified will eventually be superseded by concerns about being analyzed. We are not as mysterious as we like to think, even if the capability of computers is sometimes overhyped. Systems are being developed to interpret our feelings and moods using the tiniest of physical cues. They are said to be able to take in the sentiments of crowds in a heartbeat. They can tell if we are bored or distracted from the tiny movements of our faces. They can see if we’re sad from the way we walk. They can detect cognitive impairments from the way we poke our smartphones. They can predict our mental state from the content of our social media posts. Famously, Facebook ‘likes’ can be used to predict a person’s political preferences 85 per cent of the time, their sexuality 88 per cent of the time and their race 95 per cent of the time.

Using data gathered from a thousand sources, today’s systems scrutinize us more closely and completely than any government agent ever could. And as we will see in the next chapter, this allows them not only to interpret our cognitive states but influence them too. Tomorrow’s technologies will be even more powerful.