How did we miss the “botnet” blindspot? Ask the legends of Hollywood sci-fi

- Predicting the future is difficult because the future must make sense in the present.

- From the malicious supercomputer in 2001: A Space Odyssey to the homicidal network in The Terminator, Hollywood sci-fi tends to miss the mark.

- In real life, the computer industry has been slow to recognize the dangers of “botnets.”

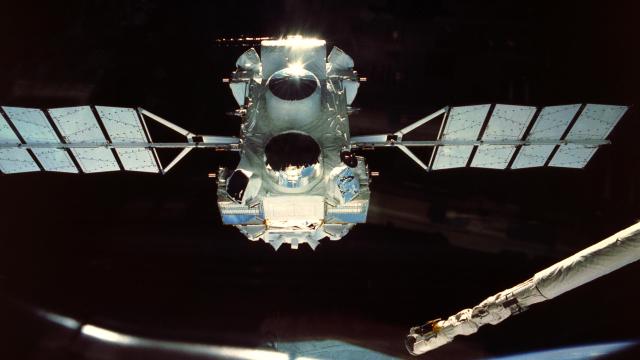

In Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 epic sci-fi movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey, the ship Discovery One rockets to Jupiter to investigate signs of extraterrestrial life. The craft has five crew members: Dr. David Bowman, Dr. Frank Poole, and three hibernating astronauts in suspended animation. Bowman and Poole are able to run the Discovery One because most of its operations are controlled by HAL, a superintelligent computer that communicates with the crew via a human voice (supplied by Douglas Rain, a Canadian actor chosen because of his bland Midwestern accent).

In a pivotal scene, HAL reports the failure of an antenna control device, but Bowman and Poole can find nothing wrong with it. Mission Control concludes that HAL is malfunctioning, but HAL insists that its readings are correct. The two astronauts retreat to an escape pod and plan to disconnect the supercomputer if the malfunctioning persists. HAL, however, can read their lips using an onboard camera. When Poole replaces the antenna to test it, HAL cuts the oxygen line and sets him adrift in space. The computer also shuts off the support systems for the crew in suspended animation, killing them as well.

Bowman, the last remaining crew member, retrieves Poole’s floating dead body. “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that,” the supercomputer calmly explains as it refuses to open the doors to the ship. Bowman returns to the Discovery using the emergency lock and disconnects HAL’s processing core. HAL pleads with Bowman and even expresses fear of dying as his circuits shut down. Having deactivated the mutinous computer, Bowman steers the ship to Jupiter.

Fans have long noted that HAL is just a one-letter displacement of IBM (known in cryptography as a Caesar cipher, named after the encryption scheme used by the Roman general Julius Caesar). Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote the novel and the screenplay for 2001, however, denied that HAL’s name was a sly dig. IBM had, in fact, been a consultant to the movie. HAL is an acronym for Heuristically Algorithmic Language-Processor.

Predicting the future is difficult because the future must make sense in the present. It rarely does. When the film was released, it was natural to assume that we’d have interplanetary spaceships in the next few decades and they would be run by supercomputing mainframes. In 1968, computers were colossal electronic hulks produced by corporations like IBM. The most likely Frankenstein to betray its creator would be a large business machine from Armonk, New York.

Hollywood missed again. The millennium came and went without a cyber-triggered nuclear war.

In the 1980s, the personal computer, the miniaturization of electronics, and the internet transformed our fears about technology. Instead of one neurotic supercomputer trying to kill us, the danger seemed to come from a homicidal network of ordinary computers. James Cameron’s 1984 cult classic The Terminator tells the story of Skynet, a web of intelligent devices created for the U.S. government by Cyberdyne Systems. Skynet was trusted to protect the country from foreign enemies and run all aspects of modern life. It went online on August 4, 1997, but learned so quickly that it became “self-aware” at 2:14 a.m. on August 29, 1997. Seeing humans as a threat to its survival, the network precipitates a nuclear war, but fails to exterminate every person. Skynet sends the Terminator, famously played by Arnold Schwarzenegger, back in time to kill the mother of John Connor, who will lead the resistance against Skynet.

Hollywood missed again. The millennium came and went without a cyber-triggered nuclear war. And for all the hype about machine learning and artificial intelligence, the vast majority of computers are not particularly smart. Competent at certain things, yes, but not intellectually versatile. Computers embedded in consumer appliances can turn lights on and off, adjust a thermostat, back up photographs to the cloud, order replacement toilet paper, and adjust pacemakers. Computer chips are now placed in city streets to control traffic. Computers run most complex industrial processes.

These devices are impressive for what they are, but they are not about to become self-conscious. In many ways, they are quite stupid. They cannot tell the difference between a human being and a bread toaster.

Just as digital networks were hard to predict in 1968, the so-called Internet of Things (IoT) was difficult to imagine in 1984. Even when internet-enabled consumer appliances emerged in the last decade, the computer industry, and the legal system, have been slow to recognize the dangers of this new technology. They failed to predict IoT botnets: giant networks of embedded devices infected with malicious software and remotely controlled as a group without the owners’ knowledge.