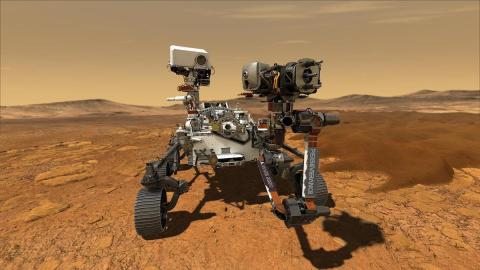

NASA’s Perseverance rover has a 1997 computer chip brain. Here’s why.

Credit: NASA

It’s probably a good idea to stop and take a moment every now and then to marvel at the incredible amount of computing power in your pocket. Today’s phones have processors that make the computers of the internet-boom era seem like little more than garage-door openers. Forget about the massive room-sized early computers that couldn’t run a game of Pong, much less Panda Pop. Nope, your pocket is packed with power.

It may surprise you then to learn that a processor that was released by IBM and Motorola back in 1997 is the chip that serves as the brain of NASA’s cutting-edge Perseverance Mars rover. The craft’s developers were more interested in reliability than sheer power, and their solution was a G3 processor, or CPU, used in Apple’s Power G3 Macintosh starting in 1998.

Credit: Apple

Apple veterans remember the G3 fondly. It was a futuristic, tower-style computer of translucent white and blue. Its side conveniently flipped open to facilitate expansion. It smoked older Macs with a processor operating speed that topped out at a screaming 266 megahertz (MHz).

Or so we thought at the time. Today’s processors leave the G3 in the dust. The processor in an Apple iPhone 12 runs at 3 GigaHertz (GHz), while a Samsung Galaxy S21 runs at 2.9 GHz in the U.S. model.

Not only that, but today’s processors are multicore chips, meaning that they’re like multiple processors running side by side within the chip. So, see ya later G3, as far as consumer use goes.

Still, the G3 was very reliable, and it was the first of a breed of chips to perform “dynamic branch prediction,” an architecture still used today. It involves the CPU predicting upcoming tasks so as to line up its processing resources as efficiently as possible.

Old G3 (left), and the new G3 for Perseverance (right)Credit: /Henriok/Wikimedia Commons

The chip in Perseverance, the PowerPC 750, isn’t even the fastest G3 chip — the single-core chip runs at 200 MHz, which is still 10 times the speed of the chips powering the Spirit and Opportunity rovers, according to NASA.

Perseverance’s chip is also not an off-the-shelf PowerPC 750. It’s a purpose-built, radiation-hardened version of the chip called the RAD750. Fabricated by BAE Systems, the processor can operate in temperatures between -55 and 125° Celsius (-67 to 257 degrees Fahrenheit), perfect for Mars’ frigid atmosphere. Also, because that atmosphere is so thin that its surface is continually bombarded with radiation, the RAD750 can withstand 200,000 to 1,000,000 Rads of radiation.

It’s also not the RAD750’s first trip to Mars: There was one onboard the Insight craft that landed there in November 2018.

NASA’s upcoming Orion craft will also use the RAD750. In 2014, when Orion was announced, NASA’s Matt Lemke explained to The Space Review that “it’s not about the speed as much as the ruggedness and the reliability. I need to make sure it will always work.” Especially attractive was the RAD750’s tolerance of radiation: “The one thing we really like about this computer is that it doesn’t get destroyed by radiation. It can be upset, but it won’t fail. We’ve done a lot of testing on the different parts in the computer. When it sees radiation, it might have to reset but it will come back up and work again.”

The designers of Perseverance were also somewhat parsimonious with onboard memory — every millimeter/gram is precious on a spacecraft. Though storage isn’t bad, at 2 GB of Flash memory, there’s just 256 megabytes of working RAM and 256 kilobytes of EEPROM (electrically-erasable programmable read-only memory).

Back here on Earth, we’re surrounded by RAD750 devices whizzing overhead in about 100 satellites. So far, not one of them has failed. No wonder the chip’s been sent on such a critical mission the Red Planet.