How About a Voucher for an Organ Later If You Donate One Now?

On December 23, 1954, Richard Herrick received the first successful live-organ transplant, a kidney, from his identical twin Ronald. The surgery was performed by a team led by Dr. Joseph Murray and Dr. David Hume at Brigham Hospital in Boston. Since that time, countless lives have been saved through increasingly common organ transplants. Sometimes the organ comes from relatives or friends — entertainer and lupus sufferer Selena Gomez recently received a kidney from her best friend — but often they’re donated by good-hearted living strangers or the recently deceased. To encourage people to donate, a new system has been proposed that would give a person who donates an organ a voucher for an organ in the future to be redeemed by a loved one.

The Problem

It’s tragic that there aren’t nearly enough donated organs available, and people die all the time while waiting for a compatible one. United Network for Organ Sharing, or UNOS, a non-profit that manages the nation’s organ transplant system, says there’s currently a waiting list of 116,590 Americans in need of an organ, with 75,472 of those listed as active candidates. 23,091 transplants were performed between January and August of 2017.

(UNOS)

New Scientist reports that 93,000 U.S. patients are waiting just for kidneys and estimates that 12 of them die each day.

To meet this need, scientists have been allocating resources to the breeding of compatible animal organ donors, one example being the piglets recently cloned using CRISPR-Cas9. Some people feel that social engineering offers a more practical, less ethically questionable option, citing the success of opt-out donor systems in other countries that result in 90% of the population donating their organs at death. The U.S. currently has an opt-in system in which donation rates are under 15%. Says bioethicist L. Syd M Johnson of Michigan Tech, “Right now, there’s very little incentive or compensation for people who donate organs. The majority of Americans say they’re in favor of donating their organs, but a fraction of them ever get that donor card, and an even smaller number make the donation in the end.”

About the New Voucher System

Howard Broadman (UCLA HEALTH)

Retired California judge Howard Broadman came up with the idea in 2014. His then 4-year-old grandson Quinn Gerlach has chronic kidney disease and is likely to need a transplant in the future. “I know Quinn will eventually need a transplant, but by the time he’s ready, I’ll be too old to give him one of my kidneys,” Broadman says. He considered donating a kidney now as a kind of abstract karmic down-payment. “But then I started thinking ‘this is bullshit – I should get something for this.’” He approached UCLA, and he and surgeon Jeffrey Veale developed the voucher system.

Veale tells UCLA Newsroom why the idea is worth pursuing:

“Some potential kidney donors are incompatible with their intended recipient based on blood type; others may be incompatible based on time. The voucher program resolves this time incompatibility between the kidney transplant donor and recipient.”

They published their plan in the September 2017 issue of the peer-reviewed journal Transplantation.

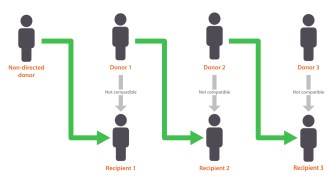

The program works like this:

This sets off a “donation chain” that allows the matching of incompatible donors with compatible recipients. Each person who donates an organ actually helps two people: the immediate recipient and the family member who gets the voucher.

The National Kidney Foundation calls this a “Never Ending Altruistic Donor,” or NEAD™ chain (NATIONAL KIDNEY FOUNDATION)

UCLA has been working with the US National Kidney Registry, which has already issued 21 kidney vouchers in 30 hospitals, each one of which initiated a donation chain that’s resulted in 68 new transplants. UCLA says their system has already saved the lives of 25 people.

Some are skeptical of the voucher system. For one thing, it’s far more complicated than other nations’ opt-out programs mentioned above, though it is less presumptive of a citizenry’s willingness to donate. Joy Riley of the Tennessee Center for Bioethics and Culture says that she’s skeptical about a system based on “trusting in a piece of paper with no guarantees.”

There’s also concern that the voucher system discriminates against those without a family member or friend willing to donate.

On the other hand, says Johnson, “We currently have a system of donation that relies on people being altruistic and proactive about donating their organs after death. But most of us are far more motivated to donate a kidney to a friend or family member than to a stranger. Would more people say yes if doing so meant that they themselves, or a friend or another family member might get higher priority should they need an organ? That seems likely, and it could help not only with kidneys, but with all lifesaving organs.” she adds, “Countries that have created incentive systems, like Israel, have seen their rates of donation increase dramatically.”