Scientists Discover Octlantis, An Octopus City off the Coast of Australia

If you’ve ever dreamed of visiting an octopus’s garden like the Beatles song portrays, you might get your chance—if you visit Australia. Common Sydney Octopuses, also known as gloomy octopuses (Octopus tetricus) were recently found cohabiting in Eastern Australia’s Jervis Bay, at a depth of 10-15m (30-45 ft.).

This particular species can be found roaming the subtropical waters between New Zealand and Australia. It was first thought that they were solitary creatures who only met once a year to mate. Instead, over the course of eight days, researchers found 10-15 of them inhabiting the same space.

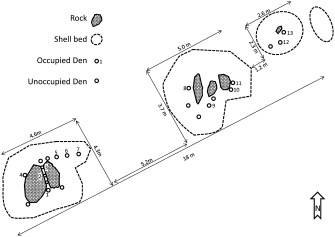

The “city” was comprised of a series of dens made out of shells leftover from mealtimes, along with beer bottles and fishing lures. This shell city was founded upon some type of metal slab. It’s too old and encrusted for researchers to tell what it is.

Within and around it, the octopuses interacted, signaling to one another, protecting mates, making art out of leftover shells, starting fights, tossing out roommates, and ignoring undesirable cohorts until they went away. Sounds more like a college dorm than a city. At any rate, the results of this fascinating find were published in the journal, Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology. American and Australian researchers conducted it. Much like the cantankerous New Yorker, the gloomy octopus might be irritable due to the cramped conditions found in its murky metropolis.

These creatures are known to be temperamental already, and they’re thought to crave solitude. Mother octopuses after mating and tending to her eggs, will take off once they’ve hatched, leaving the hatchlings to fend for themselves, which is why the discovery of Octlantis is so surprising. Although, it’s in fact the second “octopus city” to be discovered. The first was Octopolis in 2009, which is in close proximity to this one. That one’s 17m (approx. 55.8 ft.) deep.

A sketch of Octatlantis. Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology.

“These observations demonstrate that high-density occupation and complex social behaviors are not unique to the earlier described site,” researchers wrote. Discovering this second location has made them rethink their stance on octopus social behavior, particularly since generations of octopuses have been found at each site.

According to the report, finding two sites “suggest that social interactions are more wide spread among octopuses than previously recognized.” Studying these creatures isn’t easy. They’re very smart and elusive. They can blend in very well with their environment and fit themselves in the snuggest of spaces. You need to have a lot of experience in order to hunt them.

What sticks out is, octopuses make piles of discarded shells—called midden piles. These can help you spot their lair. Otherwise, you could luck out and see one swimming, but it’s rare. They’re vulnerable to predators in open water. Another stumbling block on the human side of things: the equipment needed to study them is expensive.

They’re hard to keep in captivity as well. Not only do they have specific environmental requirements, octopuses love to escape and they’re good at it. Put more than one in a tank together and they’ll fight and bicker constantly. The larger one usually wins. Even in these cities, they’re very aggressive with one another and evictions are commonplace. It’s like an extended, dysfunctional family where everyone has eight arms.

Octopuses are elusive and can squeeze themselves into small spaces. Flickr.

Studying such behavior can help us to better understand the octopus. Why is it that they’ve decided to live collectively? Some animals such as fish live together and travel in packs for protection from predators and to further commonly shared aims, like swimming faster while using less energy. Others do so to hunt more effectively. Or perhaps there’s a dearth of food in other places, forcing the octopuses to cohabitate.

Professor David Scheel of Alaska Pacific University led the study. He told Quartz, “These behaviors are the product of natural selection, and may be remarkably similar to vertebrate complex social behavior. This suggests that when the right conditions occur, evolution may produce very similar outcomes in diverse groups of organisms.”

Little actual data has surfaced thus far. Researchers found the city in the first few days of the study, dropped cameras down and started taking footage. Now, there’s a ton of it to go through. Most of what’s written in their report are impressions from among the daily recreational dives they took to the site, over the course of eight days.

Study co-author Peter Godfrey-Smith has put out an interesting book called, Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness. He said that dens give an octopus good protection against predators. In the case of Octlantis, the area northwest of the site has an exceptionally large scallop bed, a favorite food among these cunning cephalopods.

Besides doughboy scallops, there are plenty of razor clams and Tasmanian scallops to be had in the area as well. This rich bounty allows for the octopuses to tolerate one another, in order to enrich themselves. As the creatures devour mollusks, their midden piles build, which makes room for future occupants, who themselves consume shellfish, leading to an even further pile-up. Godfrey-Smith calls this process ecosystem engineering.

To see another wonder of our great oceans, click here: